Ljubljana related

April 11, 2019

In 1941 Italy and Hungary joined Germany's invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War.

On February 5, 1941, the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop expressed a demand via a Yugoslav secret envoy to Berlin for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia to join the Tripartite Pact. The Yugoslavian leadership assessed the situation and figured it would be best for Yugoslavia to follow this order. On March 25, the Pact was signed, which triggered mass protests across the country. The chaos was seized by a group of pro-British military servicemen, who carried out a coup on March 27 and put young King Peter to the throne. All of this offended Hitler personally, so he decided to postpone his plans for the invasion of the Soviet Union and strike Yugoslavia first.

Without any formal declaration of war, the attack began on Sunday, April 6th, with an air raid on Yugoslav military airports and the open, undefended city of Belgrade after that.

On today’s date, April 11th, 1941, the kingdom was also attacked by Italy and Hungary, to whom the Germans had promised parts of Yugoslav land for their collaboration in the invasion. Yugoslavia capitulated on April 17th, 1941, and the Germans took the northern part of Slovenia with Styria and Upper Carniola, Hungary occupied Prekmurje, and Italy occupied the south of Slovenia, with Ljubljana becoming the capital of their newly established Province of Ljubljana.

The video below shows the ltalian occupation of Ljubljana, repairs on the viaduct in Borovnica (Vienna-Ljubljana-Trieste Railway), which was partially blown up by the retreating Yugoslav Army, and the first military parade in Ljubljana.

All our stories on Slovenian history can be found here.

The occupation of Ljubljana by Italian Fascists lasted from April 1941 until September 1943, and was a time of horror, with around 25,000 people from the area deported and sent to concentration camps, as well as the city itself being surrounded by barbed wire. Moreover, when the Italians left the Germans moved in.

However, this story won’t dwell on these details, but instead presents some Italian archive footage showing scenes of the occupation, with many sights and buildings that will be familiar to those who only know the city today, in happier times.

All our stories about Slovenian history are here

Last week we posted an interview with Ralph Churches, a former Australian soldier who spent time as a prisoner of war in Slovenia, before escaping in a daring adventure known as the Raid at Ožbalt, or “the Flight of the Crow”. We first become aware of his story because of a new book published in English, a first person account of life as a Partisan solider in the Second World War, written by someone who was part of the same adventure. Curious to learn more, we got in touch with the translator, Robert Posl, and asked how he came to work on this project, and what he learned.

First of all, what’s your connection with Slovenia?

My parents originated from the former Yugoslavia. My father from near Rogatec, my mother from Croatia, near Zadar. She moved to Slovenia, where she met my father. In 1970 they moved to Germany. My father simply did not see a future staying in Yugoslavia.

I was the third child, born in August 1974. In spring of 1975, we moved to South Africa. The apartheid regime of South Africa was in full swing and was encouraging and inviting people to move to South Africa. So that's what my parents did, along with their three toddlers. I obviously don't remember any of that, since I was barely six months old.

We lived quite a decent and progressive life in South Africa. We as children had no contact with Yugoslavia. And even though my parents had brothers and sisters in Yugoslavia (Slovenia and Croatia), they too had almost no contact. The Communist way there was distinct and powerful until the 90's, when everything started to change. The war in Slovenia was short, only four days, with barely any conflict or anything.

Slovenia was then 'free' and with a promising future, quickly stepping forward to becoming a European nation. We started hearing about relatives we had never heard about before. Then in December 1991 my uncle and his wife came to visit us in South Africa. While things were looking quite promising for Slovenia, the opposite was for South Africa, as the apartheid era was coming to an end. So the obvious happened, the decision to move to Slovenia quickly grew.

Robert Posl

And so you moved back?

Yes, and after moving from South Africa to Slovenia, to Europe, I felt that I was now properly introduced to history. Moving from a country which has bareky any history compared to that of mainland Europe. Most of the countries in Europe have also put significant efforts into maintaining and restoring their cultural heritage, so now I could see and even touch it, compared to only reading about it. Slovenia is thus dotted with numerous buildings and monuments, which clearly express its history. Especially the countless number of memorials and plaques reminding us of the Second World War.

One thing I heard about a lot about the Partisans. The most common thing I’d hear was how difficult it was and how they lived in poverty and in hunger, with ragged clothes and inadequate equipment. My reaction was obvious, “who would want anything like that? So unpleasant!”

So that’s how you came to translate this story?

Yes and no, because there’s more of a family connection than just an interest in history. Some years ago my wife’s uncle, Alojz Voler, published his autobiography and experiences during the war, when he served with the Partisans. Alojz kept the publication quite quiet, mainly only sharing it with relatives and acquaintances. I paged through it a couple of times, reading some sections and admiring the photos.

Then in the spring of 2017, a car with foreign registration plates stopped in front of his house. They were from England, except for the translator who was with them. They were looking for a man who was involved in a remarkable event during The Second World War, “The Flight of the Crow”. A team were in Slovenia making a movie about this great event, something most people didn’t even know happened.

When I learnt more and that Alojz was involved in it, I right away suggested that his autobiography be translated into English and to include the details of this event. The more I thought about it, the more I saw the need for this to be done.

Alojz Voler, with German recruits. He served in the German army for 14 months before he managed to desert them and return to Slovenia, where he then joined the partisans.

What was that like?

I got to know more of the details and specifics about Alojz and the life he lived. He was born in 1925 on a farm in the Savinja Valley in Northern Slovenia. Not only was I getting to know him, but I was also getting to know what it was like living in that period. The onset of the Second World War and the influence of the aggressors, which was long felt before the conflict even started.

The Second World War was for Yugoslavia more than just the invasion and engagements with German forces. A significant part of it was the tension and politics within the country itself. Already in primary school, Alojz would be tolfd negatuve things about the Partisans, and how they lived in hunger and poverty. Surprisingly, it was allo very to what I so often heard when I moved to Slovenia.

For Alojz to follow his heart was a journey in its self, and to join the Partisans was an almost unimaginable and treacherous step to make. I admire how Alojz expresses this idea: To go into resistance with almost bare hands, against the most elite forces of the world at that time, was an almost fantasy. But it was no fantasy, it was the cruel reality.

Starting with this translation at first only fed fuel to the fire of my curiosity. What kind of person, and why, would want to be part of the Partisans? But by following Alojz’s life throughout his book, my questions were answered.

Alojz on the right, with other members of the KNOJ (Korpus narodne obrambe Jugoslavije). Photo taken after the war ended.

The book obviously has many other stories, but how was Aljoz involved in the “Escape of the Crow”?

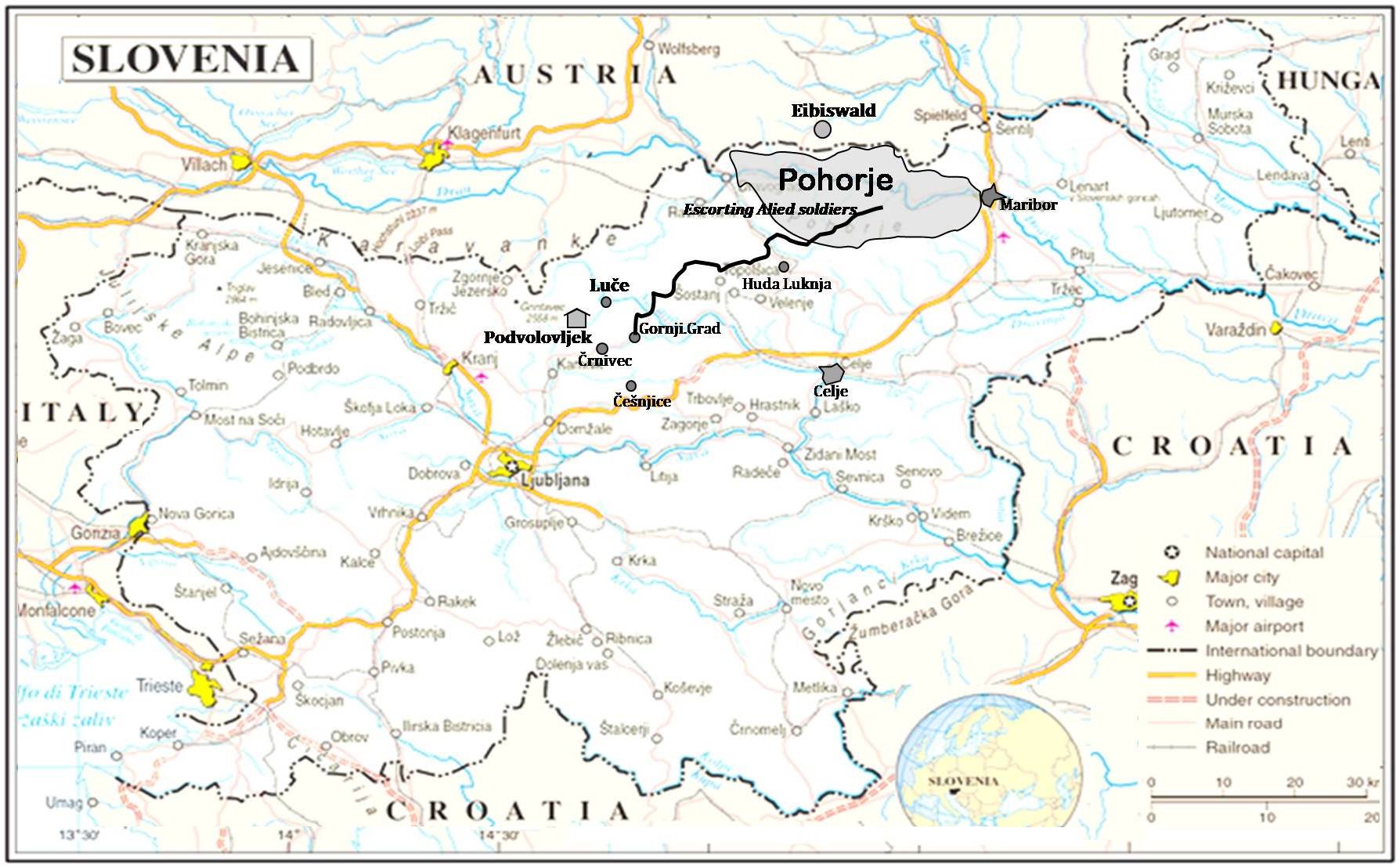

The battalion Alojz was in was based to the west of Maribor, nearby the Ožbalt work camp. Some of the Partisans were chosen to escort a group of six POWs, including Ralph Churches, away from the area ASAP. The next day they returned and managed to free the rest of the captives, and it was then that Alojz met and helped them to safety and away from Ožbalt before the Germans intensified their search for the prisoners.

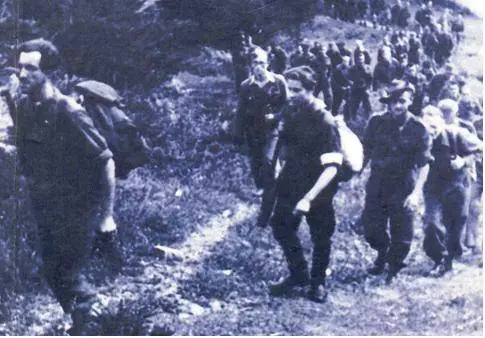

Here is a photo, which is also on the cover of A Hundred Miles as the Crow Flies. The guy on the left, almost out of the picture is Franjo Gruden, the leader of the escort team. Alojz was at the back to make sure nobody fell behind.

And here is a map I made for the book. You can see where they went, up to Gornji Grad, then another group of partisan soldiers took over to escort them further.

And what you have learned from the book?

For me the most important things about working on this project are being able to share a part of history, but more than that, it’s about giving Alojz that feeling of pride. At 94 years old it’s quite something that his story is finally being told, and that he’s the one to tell it. And so I hope that more people will hear about him and what he did during the war.

While doing the translation, and still after, people would ask me: “Who is paying for this? How much are you being paid?” My answer – Alojz has paid me; with the truths and experiences from his heart, as seen by an ordinary, humble man. And with the knowledge, that I can now confidently say, “I know who and what the partisans really were”.

Alojz Voler, Niel Churches & Monty Halls, Spring 2017

If you’d like to read Alojz’s story, Through the Eyes of a Partisan Soldier, then you can pick up a copy, in both paper and digital forms, from Amazon, while all our stories on World War Two are here

Ljubljanska tržnica 1934 from matjaz zbontar on Vimeo.

STA, 25 February 2019 - Following President Borut Pahor's recent assessment that the work of the government commission for mass graves has "become not only socially acceptable but also socially accepted", substantial progress in the field has also been confirmed by the commission's vice-president Mitja Ferenc.

So far 233 mass graves and post-WWII execution sites have been confirmed and registered in Slovenia. Full or partial reburial was performed at 129, while the the existence of body remains has been confirmed for the remaining 104, Ferenc told the weekly paper Reporter.

The historian attributes major importance to the 2015 act on concealed mass graves and the burial of victims, adopted under a centre-left coalition at the initiatives of the centre-right opposition New Slovenia (NSi).

In the last three years, 162 summary execution sites were marked and tended to. The remains of at least 2,532 bodies were discovered in them and 1,615 were buried, he said.

Related: Mass Concealed Graves in Slovenia, an Interactive Map

The commission's main project presently is the Larch Hill mass grave in the south-east of the country, where he hopes exhumation will already start in the spring.

Expecting to discover around 1,500 victims, Ferenc said "the objects found near the pit indicate that Slovenian victims lie inside".

While asserting that the EUR 480,000 allocated to the commission by the state annually suffice for its tasks, Ferenc is not happy with the attitude of the Economy Ministry.

He said legislation tasked the commission with a large number of tasks that are demanding and require assistance. A key issue are delays in tenders and unreasonable deadlines, which for instance give the commission six weeks for reburial on demanding terrain and winter conditions.

Meanwhile, Ferenc said that concealed mass graves are not the only problem in Slovenia: "We have a neglectful attitude to all grave sites, including those of the Partisan forces. They are not looked after, the registry is not systematic, there are also sites that do not really contain any victims."

Ferenc, who said it was time to stop looking away, announced an initiative to establish an institute for war graves, to be presented on the occasion of the nearing tenth anniversary of the entry into Huda Jama, a site which contained 1,416 victims.

February 10, 2019

Read part one here and part two here.

The main task of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society (Slovensko Planinsko Društvo, SDP), established in 1893, was to build, take care and then walk along the secured mountain trails. One of the first important improvements on Triglav was securing some of the most problematic parts of the route leading to the summit. In the early 1870s, a local guide, Šest, and his son eased the trail from Triglav temple to Little Triglav, cut some very much needed steps into the rock, and secured the ridge between both peaks with iron poles with loops that carried a rope fence, which now allowed even more climbers to reach the summit.

In the years that followed, more trails were built and secured, allowing the ascent to the summit from several huts in various directions, including from the north. This is a route which used to cross the shrinking glacier, but today leads to Kredarica, the most popular starting point to reach the summit since Jakob Aljaž found a great spot for a hut which was built there in 1896.

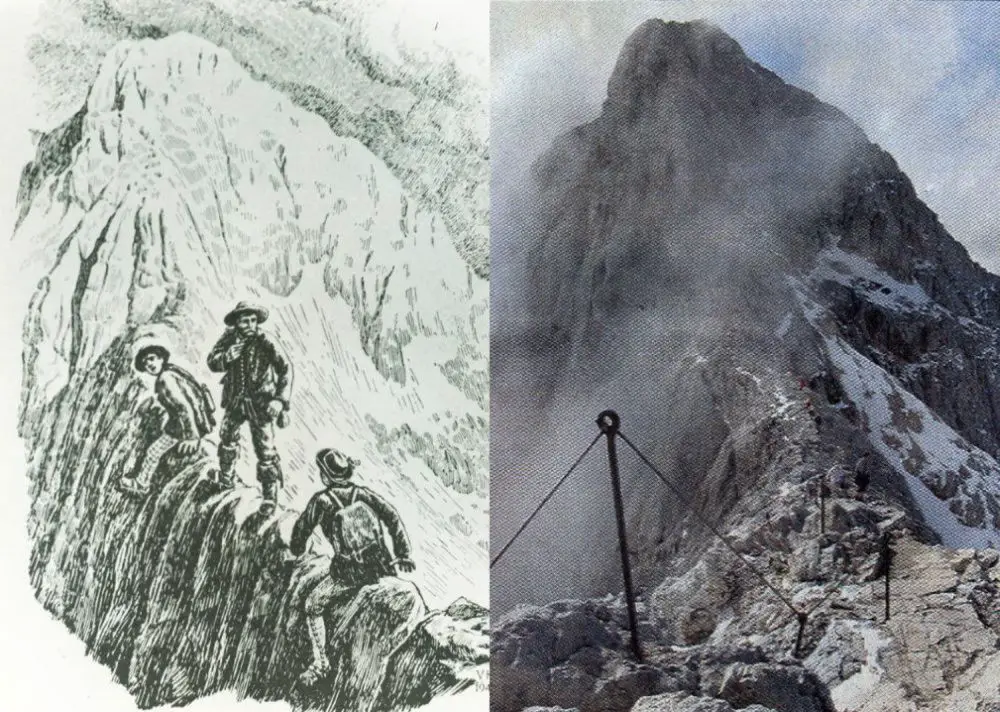

However, the Slovenian Mountaineering Society did little for a small group of daring young climbers, who were more interested in new routes than tourist walks on known and secured trails. On Triglav, this meant climbing the Northern Wall, one of the largest of its kind in the Eastern Alps. It's 1300m high (following the German route) and 3500m wide, with several shelves and ravines forming independent walls within the big one. Triglav’s Northern Wall is also home to several of the hardest climbing routes in the Slovenian Alps.

Triglav Northern Wall

Although the first climbers of the Northern Wall were shepherds and hunters, who mostly followed the paths of animals, sports climbing was based on a different kind of logic from that which found a path that was shown to a “gentleman” by a hunter, as the so-called Slovenian route across the Northern Wall was shown by a guide (Komac) to Henrik Tuma in 1910. If the new route for the older generation meant an easier path across a newly climbed slope, the new view on alpinism involved climbing a new, more difficult route without cleared paths and instead with the help of pitons and ropes.

Triglav’s Northern Wall was considered one of the three main problems of the Eastern Alps before it was even climbed, and as such was the focus of German, Austrian and Czech climbers. After the walls of Watzmann (1888) and Hochstadl (1905), the wall of Triglav was finally climbed by three Austrian Germans, Karl Domenigg, Felix Koenig and Hans Reinl, in 1906. The route has become known as the German route, and their success was immediately followed by several failed attempts, some even fatal ones.

Dren Society

In 1908 the Dren society was established, a group of students interested in Alpinism, skiing, caving and photography, novel activities outside the usually promoted Alpine tourism of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society, whose members considered them as “neck-breakers”.

Slovenian Alpinism before World War One was still way behind the developments in other parts of the Alps. The first use of a piton by a Dren member, Pavel Kunaver, is only recorded in 1911, which is also the last year of attempts at the Northern Wall until after the war.

Although Dren members did introduce some novelty into Slovenian climbing, such as winter ascents (sometimes accompanied by skiing) and other more adventurous climbs, their equipment and technique at the time only allowed them to climb routes of the third level of difficulty, and their predecessor and colleague Henrik Tuma hadn’t climbed anything beyond that level either.

This situation can be seen in the fact that the abovementioned German route on the Triglav Northern Wall, which had the climbing difficulty of level IV, was the most difficult route in Slovenian mountains at the time. Hans Reinly, one of the three first climbers described the achievement with the following words: “Triglav rises its triple head angrily. Let it be called Slovenian highest mountain, but this time it was the German force that conquered its most terrifying hip and fought through dark fogs which driven by a storm descent into the depth from the grey ice at the edge of the wall.” Worth mentioning is that in those days there was no meteorological report, and the day and a half climb took place in rain and bad weather.

The guiding ideas of the Dren were to conquer Slovenian mountains before the German mountaineers, try to prevent the Germanisation of Slovenian mountain names, and to climb without mountain guides, which was the main mountaineering style of the time. Lack of manpower and resources prevented these goals being fully achieved, although the ideas persisted throughout the interwar period and became perhaps the main reason behind the increasing Slovenian obsession with Alpinism, which eventually produced some of the best climbers in the world and continues to do so, regardless of the small the size of the place and its population.

Triglav in the Interwar period

After the war, and let’s not forget that one of the bloodiest WWI fronts took place right at Triglav National Park’s eastern border across the banks of the River Soča (the Battle of Isonzo), the main concern of the Slovenian Mountaineering Society was mostly fixing what had been damaged or destroyed.

Furthermore, the Austro-Hungarian Empire fell apart and Slovenia joined the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. It turned out, however, that in 1915 the Triple Entente had signed a secret agreement with Italy, promising it large chunks of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in case of victory. With the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo Italy managed to claim most of the lands promised to her by the United Kingdom, Russia and France, which set the Italian-Yugoslav border at the peak of Triglav, a couple of metres away from Aljaž Tower.

Originally, the entire peak of Triglav was to belong to the Kingdom of South Slaves, however, Italy pushed very hard to get the land under its jurisdiction. The dispute was even more meaningful given that it was part of an attempt to extend poor conditions the Slovenes on the other side of the border had to endure in the face of the rising Italian fascism. The negotiations lasted for four years, and while waiting for the final decision certain incidents took place at the top of Triglav, in the summer of 1923 in particular. These are often referred to as “painting battles” but did in fact involve a more serious weapons beside the paintbrushes, which were used to paint Aljaž Tower with slogans and flag colours. Luckily, nobody got hurt, Aljaž Tower was eventually repainted to its original grey, and the final decision on the border in 1924 set the boundary marker 2.55m west from the Aljaž Tower, rendering the summit it effectively Slovenian.

Tourist Club Skala

Within the Slovenian Mountaineering Society (SPD) friction between the moderates and those advocating for “steep tourism” continued into the interwar period. Since the majority of members would not allow sports climbing to be recognised within the SDP, young mountaineers splintered off into a Tourist Club Rock (Turistovski klub Skala, TK Skala) in the winter of 1921.

Rock’s main goal was to continue the development in sports climbing started by Henrik Tuma and evolved by the Dren Society. Among the important climbing achievements of TK Skala are the first Slovenian level V difficulty route climbed by a female climber, Mira Marko Debelak, in 1926 (at the north face of Špik), and the first fully successful winter climb of Triglav’s northern wall in 1939 by Beno Anderwald, Mirko Slapar, Bogdan Jordan and Cene Malovrh, who since 1934, when the SPD finally took alpinism under its wing, had also been members of this organisation.

Foremost, however, Skala’s important achievements also extended into the field of art and culture. Like Dren, TK Skala promoted mountain photography and established a special photography department in charge of postcard production and other images for propaganda purposes. But above all, they were responsible for the first Slovenian feature film, the 1931 V kraljestvu Zlatoroga (In the Kingdom of the Goldhorn) and partially also for the second one a year later, Triglavske Strmine (The Slopes of Triglav). The first movie was produced by Skala and directed by one of their members, Janko Ravnik, while the second was produced by an independent film studio, although it featured several mountaineers/actors from the first film, including Miha Potočnik and Jože Čop.

February 7, 2019

In 1942 the underground anti-fascist Radio Kričač (Radio Screamer) broadcast its longest and also the only cultural show of this kind in Europe.

On the eve of Prešeren's death, which is celebrated every February 8th as a day for culture and national holiday in the Republic of Slovenia, Radio Kričač broadcast a show that took about a month to prepare and involved recitals, music, speeches and other messages. Its usual programme would otherwise last 15 minutes three times a week.

Radio Screamer, established by members of the Liberation Front (OF – Osvobodilna fronta) operated from various secret locations in Ljubljana between November 1941 until April 1942, when it lost its audience following the Italian order for all the radio antennas to be removed from the city.

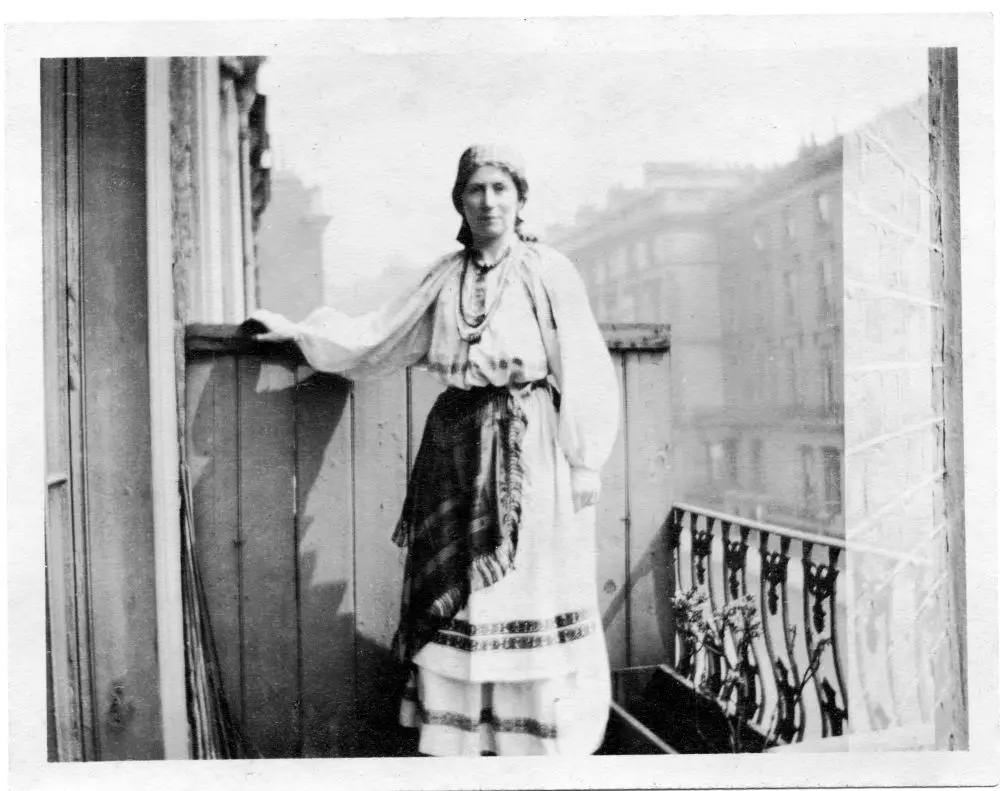

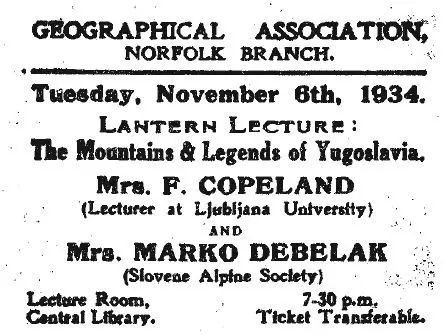

Fanny Susan Copeland was a remarkable person whose life serves as a curiosity and inspiration. A British woman who was born in Ireland in 1872, grew up in Scotland, and moved to Slovenia in 1921, where she spent most of the rest of her life, dying at 98 in 1970, and buried at the foot of Mount Triglav.

Although she wrote an autobiography it was never published and will remain in copyright limbo until 2020. One person who’s seen this memoir is Eric Percival, whose great-great-great-grandfather, Fred Holloway, knew Fanny’s father, Ralph Copeland, once the Astronomer Royal for Scotland, with the two men meeting near Manchester in the early 1860's. Percival put together the original post that sparked my interest in Ms Copeland, and also kindly supplied some of the pictures that accompany this story. Unless otherwise stated, the facts set out below are also drawn from his account of her life, as based on her own and other reports.

Although British by birth, Fanny was a thoroughly European woman, learning French and German as a child and being educated in Berlin shortly after turning 13. She also learned Latin, Italian, Danish, Norwegian and – due to her father’s interest in the Balkans – Slovenian. This connection with the country would be enough to get our attention, but Ms Copeland holds it because she bucks the standard narrative in terms of when and how one can make a new life for oneself. A brief outline of that life is as follows.

Fanny got married in 1894, at the age of 22, to escape her mother, but her husband was a 36-year old man who she never really liked. The couple had three children and then separated in 1908, finally divorcing in 1912, when Fanny was 40.

She developed a stronger connection with what would eventually become Yugoslavia soon after this, during the First World War, when she supported herself by doing translating for London-based South Slavic organisations. As part of this she translated Bogumil Vošnjak’s Bulwark against Germany: The fight of the Slovenes, the western branch of the Jugoslavs, for national existence, as well as serving as translator for the South Slavic delegation at the Paris Peace Conference.

In "traditional costume"

With Oton Župančič at the Congress of Dubrovnik in 1933

Ms Copeland then moved to Ljubljana in 1921, aged 49, when the city was part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. She was hired as a lecturer in English at the University (which itself only opened in July 1919), a post she held until 1941, when the Germans invaded. At this point, aged 69, she was arrested by the Gestapo and handed to the Italians, who moved her to Trieste, then to Arezzo and finally Bibbiena (in Etruria), where she spent the rest of the war “in open confinement”.

In 1953, aged 81, she finally moved back to Ljubljana. The death of her brother meant that she now had some savings, and thus Fanny Copeland lived in Hotel Slon for the rest of her life, continuing to work as a writer and translator.

Ms Copeland, right, in the Hotel Slon, late 1960s

A pioneer of mountaineering tourism in Slovenia

But Fanny Copeland isn’t just a fine example of a person who didn’t let their gender or age dictate what they should be doing and when, or of someone who managed to successfully integrate themselves into a new country, as she also played a key role in the development of Alpinism as a local tourist offering, and in the promotion of Slovenia as a tourist destination. This section thus draws from an article by Janet Ashton called “Buried at his feet”: Fanny Susan Copeland, Triglav and Slovenia, and from another, Fanny Copeland and the geographical imagination, by Richard Clarke and Marija Anteric, both of which are recommended for more detail.

Ms Copeland felt a great attraction for the Julian Alps, and Slovenia the Slovenes in general, claiming they were the most Scottish of the Yugoslav communities, perhaps because of the mountains, long dominance by other powers, and characteristics of pragmatism and frugality.

She first climbed Triglav in the 1920s, not having taken up serious climbing until her 40s, and did so for the last time in 1958, just before her 87th birthday. She also wrote two books on the Julian Alps, Beautiful Mountains: In the Jugoslav Alps (1931), and A short guide to the Slovene Alps (Jugoslavia) for British and American tourists (1936). As she said in 1957, this was done in the “hope of attracting to Slovenia tourists of all types, from summer visitors in search of little-known beautiful and inexpensive Alpine resorts to Alpinists in search of accessible mountain ranges not yet wholly exploited or explored”.

"Ambassador for the beauty of our mountains". www.gore-ljudje.net

Such efforts to reveal what in those days was still a very hidden gem were not without their obvious dangers, as she noted in a much earlier letter from 1923 when commenting on one of her many trips up Triglav: “It is an interesting walk, but as an expedition it is badly spoilt by the path having been made fool-proof. Result, every holiday is made hideous by hundreds of trippers, and the average person has to wait for a holiday to go up.”

Slovenski planinski muzej:- Fedor Košir, president of the Alpine Association of Slovenia and Fanny Copeland.

As mark of respect for her work to promote the Julian Alps, and to establish Triglav National Park, when Fanny Copeland died her funeral was organised by the Mountaineering Union of Slovenia. She was buried in the cemetery of the village church in Dovje, where you can still see her simple grave, as shown below.

Wikipedia - Miran Hladnik CC-by-2.5

As Copeland wrote in 1931:

By fixed custom those that perish on Triglav are buried at his feet. In the pretty village church of Dovje, opposite the entrance of the stately Valley of the Gate (Vrata– truly a gate to be called Beautiful) they lie side by side. I think they would have it so. The long shadows of the regal avenue of peaks, down which they passed to their last adventure, sweep over their graves as the days and the years roll by; on All Souls’ day the mountaineers bring them pious offerings of prayer and lights, and from their tombstones their names cry greeting and warning to the hosts that go up year by year to visit the mountains, - greeting to the many who go up by the blazed trail where every danger spot is made safe with iron bolt and wire rope, to protect the unwary and put heart into the timid, - greeting to the few who seek, like themselves, to win the goal without guidance save the love of the heights, and no company except the extreme mysteries of life and death – greeting to the cragsman and the lover, to schoolboy and hunter, to smuggler and spy, and the ski-shod friend of the snows….

So if you find yourself in Hotel Slon, on Mount Triglav or by the village of Dovje, spare a thought for the remarkable Fanny Copeland, a woman who not only did as much as anyone else working in English to make the case for a separate Slovenian identity, one distinct from land’s association with the Habsburgs, Slavs and Serbo-Croatians, but also did much to bring the beauty of the land to a wider audience, and to share the best of her adoptive home with the world.

Postscript

As to what life was really like under Tito for a woman born to the academic elite under Queen Victoria, Copeland addresses this at the end of her autobiography, with a postscript to the reader:

But have you really found good reasons to go and live in a ‘communist’ state? This was a question I was often asked soon after my return to Ljubljana. Well - for one thing it depends on what you mean by 'Communism'. If you mean a totalitarian regime then my reply is that no Yugoslav would put up with such a system… The Yugoslavs are stout individualists, but they appreciate law and order. Ask any British tourist who has visited Yugoslavia in recent years.

All our stories on mountaineering in Slovenia can be found here

STA, 4 February 2019 - Slovenska Matica, the nation's oldest cultural and scientific society, is celebrating its 155th anniversary with an open house on Monday. A number of lectures, debates and presentations are taking place. President Borut Pahor addressed the main ceremony.

Slovenia is confronted with the question of how to build its national character without it turning to national arrogance or nationalism, Pahor said in his address, adding that this was a sensitive and tough intellectual and political issue.

At the same time, Slovenians need to ask themselves "how can we build stable pillars of sovereignty without creating the impression that we started to doubt the European idea and were getting ready for its downfall".

He pointed to the important role Slovenska Matica played in this context and noted that these issues needed to be addressed with great sensitivity, especially by politicians.

Slovenska Matica president Aleš Gabrič said in his address that the society wanted to continue to do the work it set out to do 155 years ago: "to bring into the treasure trove of the national cultural wealth that what makes the nation its best".

The society was established in Ljubljana with donations of academics, tradesmen and entrepreneurs with the objective to print academic and scientific books in Slovenian.

Slovenian was not a language of academia, as Slovenian lands were a part of the Austrian Empire up until its dissolution following World War I.

When it was established, the society's mission was to raise the level of education across the nation and create Slovenian vocabulary in a variety of fields.

The society's heyday was in the early 20th century, when the books it published reached high circulation and the society nurtured frequent contacts with universities and academic societies from London to St Petersburg.

Today, Slovenska Matica is the second oldest Slovenian publisher after Mohorjeva Družba. It organises science meetings and conferences addressing issues faced by the Slovenian culture and society. It is fully funded by the state.

January 30, 2019

In 1810 the French army seized and then executed a group of bandits called rokovnjači, who had previously attacked them in Črni Graben.

The first wave of this organised banditry in central Europe occurred during and after the 30-year War (1618-1648). The rokovnjači problem in what is today Slovenia was particularly pressing between the years 1808 – 1813 during the French occupation of these territories, when the bandits were even assisted by the Austrian court, and then after Austria regained its territories from Napoleon’s army the problem turned on her in an ever stronger fashion between the years 1825-1853. Rokovnjači were most numerous in Upper Carniola and in the Kamnik area, but could also be found in the Littoral.

The main causes of the phenomenon lay in the 1770 Maria Theresa decree which replaced her army of mercenaries with a 30-year period of military service for everyone poor and uneducated enough not to be able to avoid it, and the 1785 Joseph II abolition of serfdom, which freed the serfs not only from their masters but also from their land. These young deserters who were later joined by a variety of other social outcasts joined the ranks of rokovnjači, and lived lives revolved around hiding in the remote places of dark forests and their night hikes to towns and villages, where they begged, robbed, and terrorised the population.

The name Rokovnjači, sometimes also rokomavhi, comes from the folk belief that these bandits carried an arm (roka) of an unborn baby in their bags (mavha) which would then give them some magic powers such as make them invisible when in trouble or giving them a light in the dark that only them could see. It was believed that rokovnjači would cut babies out of pregnant ladies, chop their arms off and then dry them over a juniper berry wood fire, which is why no pregnant woman was allowed to wander around on her own. Belief in the magic of a child’s arm was not only present in the area of present-day Slovenia but, just like rokovnjači themselves, across Southern Germany and Austria as well. Jakob Grimm – the elder of the two famous brothers – describes in his book on German mythology (Deutsche Mithologie, 1835) the magic properties of the fingers of a pre-born baby; if they are set on fire the resulting flame would put everyone in a house to sleep, preventing them from waking up.

It was not against the interests of rokovnjači to be feared among the locals, who preferred to cooperate and support them in goods and information than to risk violent repercussions. On the other hand, they also tended to be helpful in poor farmers’ fights against the various forms of exploitation coming from the church, landowners and forceful conscriptions. Rokovnjači were well organised, which included a sort of a proto-Marxist ethics – that theft was justified by the ideas of equality and the right to survival. They also had their own secret language, which was a mix of various European ones, including German, Italian, Hungarian, Croatian and Slovenian. For example, “Ti lobov kumer'č, d'tej prefak upetov!” stood for “Ti slab človek, da ti je duhovnik ubežal!” (You bad man, let the priest escape you!).

In 1810 rokovnjači attacked and robbed a group of French soldiers in the Črni graben valley, which was a reason for the French army to retaliate. Not all of them were caught, but those that were were hung on today’s date in 1810. On February 12, Napoleon decided to establish gendarmerie stations in the most affected areas, known by the locals as “ravbarkomanda”.

In the third wave of banditry between the years 1825 and 1853, rokovnjači multiplied to the point the skirmishes began even among their own ranks. The affected population began to beg the authorities to do something about it. In 1850 the long awaited hunt of Austrian gendarme for the out-of-control bandits began. The new imperial decree, which reduced the military service to eight years in 1845 and again to six years in 1850, helped to reduce their ranks as well. No more was heard about rokovnjači after 1853.

A novel Rokovnjači (1881), written by Josip Jurčič and Janko Kersnik, continues to serve as an inspiration for various stage adaptations, one of them, a coproduction of the National Theatre of Nova Gorica and Prešeren Theatre Kranj, is embedded in the video below.