Ljubljana related

May 22, 2019

With the European parliamentary elections approaching it is perhaps appropriate to look back in time at the polity that used to rule these lands in the late Middle Ages, when “nations” didn’t exist, and the rising Ottoman Empire was the main external threat to the ruling families of the Holy Roman Empire.

One of the most successful feudal families that emerged in the present-day Slovenia and seriously challenged the dominance of the Habsburgs were Counts of Celje (GER: Grafen von Cilli), who were elevated to the rank of Princes in 1436, following a successful series of military campaigns and the marriage policies of Hermann II.

Hermann II, who is mostly known to Slovenian historic memory as the person who killed his daughter-in-law Veronica of Desenice, managed to establish a relationship of trust with King and later Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, expand his family’s territories from Styria deep into the Balkan and set the stage for his grandchild Ulric II to attempt to take the Hungarian throne. With Ulric’s death, however, the male line of the Counts of Celje was extinct and their estates went to the House of Hapsburgs, who were in a mutual inheritance contract with the House of Celje.

Hermann II and his political ambitions

In 1388 Hermann II arranged the marriage of his first born son Frederick III with Elisabeth of the Frankopans, both babies at the time. Hermann’s goal was to establish a principality – a political entity subservient directly and only to the King. The marriage with the Frankopans, a Croat noble family, would help ease resistance in Slavonia that started to build up against the House of Celje due to its expansion into the Balkans. He also managed to secure a generous dowry that Elisabeth brought into the family, which included several estates in Kvarner on the Adriatic coast.

While the engaged were growing up, each with their own families, Hermann II made a smart move by joining King Sigismund of Luxemburg in his 1396 Crusade of Nicopolis, which was to save Constantinople and Byzantine Empire from the Ottoman Turks. During the campaign he saved Sigismund’s life and the King promised him to marry his daughter Barbara in return. Through this marriage, Barbara, once old enough, became the Empress of the Holy Roman Empire after Sigismund was elected Emperor in 1433.

Frederick II of Celje and Veronika of Desenice

The plans Hermann II had for oldest son, Frederick II, however, didn’t go as he envisioned. When Elisabeth and Frederick were finally married in 1404 or 1405, they did not get along very well. Elisabeth gave birth to two boys, Ulric II and Frederick III, the latter dying in early childhood. The couple lived separately from 1415 until Elisabeth’s suspicious death in 1422. How and where Elisabeth died is not very clear. According to one of the stories, especially popular among Frankopans who wanted Elisabeth’s dowry back, Frederick II strangled her so that he could get married with his mistress, Veronika of Desenice.

Before Elisabeth’s death, Frederick met a girl from a lower class in the village of Desenice and fell in love with her. In 1424 or 1425 Veronica of Desenice and Frederick II of Celje got married, and Frederick built a Friedrichstein castle above Kočevje, where they would presumably live happily ever after.

With this marriage he fell out of favour not only with the Frankopans, who took back control of the territories that had been included in Elisabeth’s dowry, but also his father Hermann II, whose political achievements he wasted, and the Hungarian court under King Sigismund, who felt obligated to his father.

In 1425 Frederick II applied for asylum in Venice, claiming that his father and the Hungarian court were attempting to kill he and his wife, but the senate of the city state turned him down. Somehow King Sigismund managed to lure Frederick to his court where he was captured and handed over to his father, who threw him in jail and demolished Friedrichstein Castel.

Veronica was hiding in monasteries and forests until she was captured as well. In order to clear his son’s name in front of other noble families, Hermann headed to court accusing Veronica of witchcraft. He failed, the court found her not guilty. Hermann II then jailed Veronica in Ojstrica castle where she was drowned in a tub by Hermann’s guard on October 14, 1425.

Frederick, however, didn’t stay in prison for very long. In 1426 his only remaining brother Hermann III died. The only heirs of the Counts of Celje now were Frederick II and his son Ulric II, so Hermann II released his son from jail.

Principality of Celje

The relationship between Hermann II and Frederick II smoothed a little, but the two remained rivals. Hermann II was now reluctant to entrust Frederick with management of the family estates. In 1429 Frederick was given the title Count of Zagorje by King Sigismund of Hungary, something Hermann probably opposed. In 1435 Frederick II rebelled against his father by demanding concessions from the Hungarian King, now also the Holy Roman Emperor, , placing Sigismund in the middle of the dispute he had with his father. These trouble stopped with Hermann’s death. On November 30, 1436, Frederick II and Ulric II were elevated to the ranks of Princes, which came with power granted to them over jurisdiction, currency production and mining.

The Princes of Celje now became legal contesters for the Empire’s crown, which endangered the unity of the Habsburg estates. Between the years of 1436 and 1443 a war ensued between the two families. Although the House of Celje proved stronger in the battlefield, they had to accept the ceasefire as by then Frederick III of the Habsburgs was already crowned a King. In 1443 a mutual inheritance contract was signed by the two families in case of dynastic extinction.

Meanwhile, Sigismund died in 1437, which triggered the succession crisis for the Hungarian crown. Ulric II entered the intrigues that followed, and Frederick II helped by engaging in diplomatic missions, mobilizing the family’s vast connections abroad. Frederick II died in 1454, and a year later second Ulric’s son died as well, rendering Urlic II the sole surviving heir of the House of Celje.

The end of the House of Celje

In 1456 Ulric II was assassinated by the rival House of Hunyadis from Transylvania, while accompanying Hungarian King Ladislav to Belgrade. This meant that the House of Celje was extinct and according to the mutual inheritance contract, Habsburgs became legal heirs of their estates, setting the stage for the Austrian Empire.

May 13, 2019

In March 1938 a small stream called Nevljica was being regulated and a bridge was planned to be built across it at Nevlje, near Kamnik. Mayor Nande Novak supervised the works at the construction site, when one day the workers complained that they’d hit an obstacle – tree stumps, they said.

The mayor looked at the “stumps” and recognized them as bones but had no idea what kind of creature they once belonged to. He stopped the works and sought advice from Josip Sadnikar in Kamnik.

Josip NIkolaj Sadnikar (1863-1953), a veterinarian by profession, was an enthusiastic collector of antiquities since his years in high school. In the “stumps” that were brought to him he recognized an extinct mammal, a mammoth, which had died about 20,000 years ago.

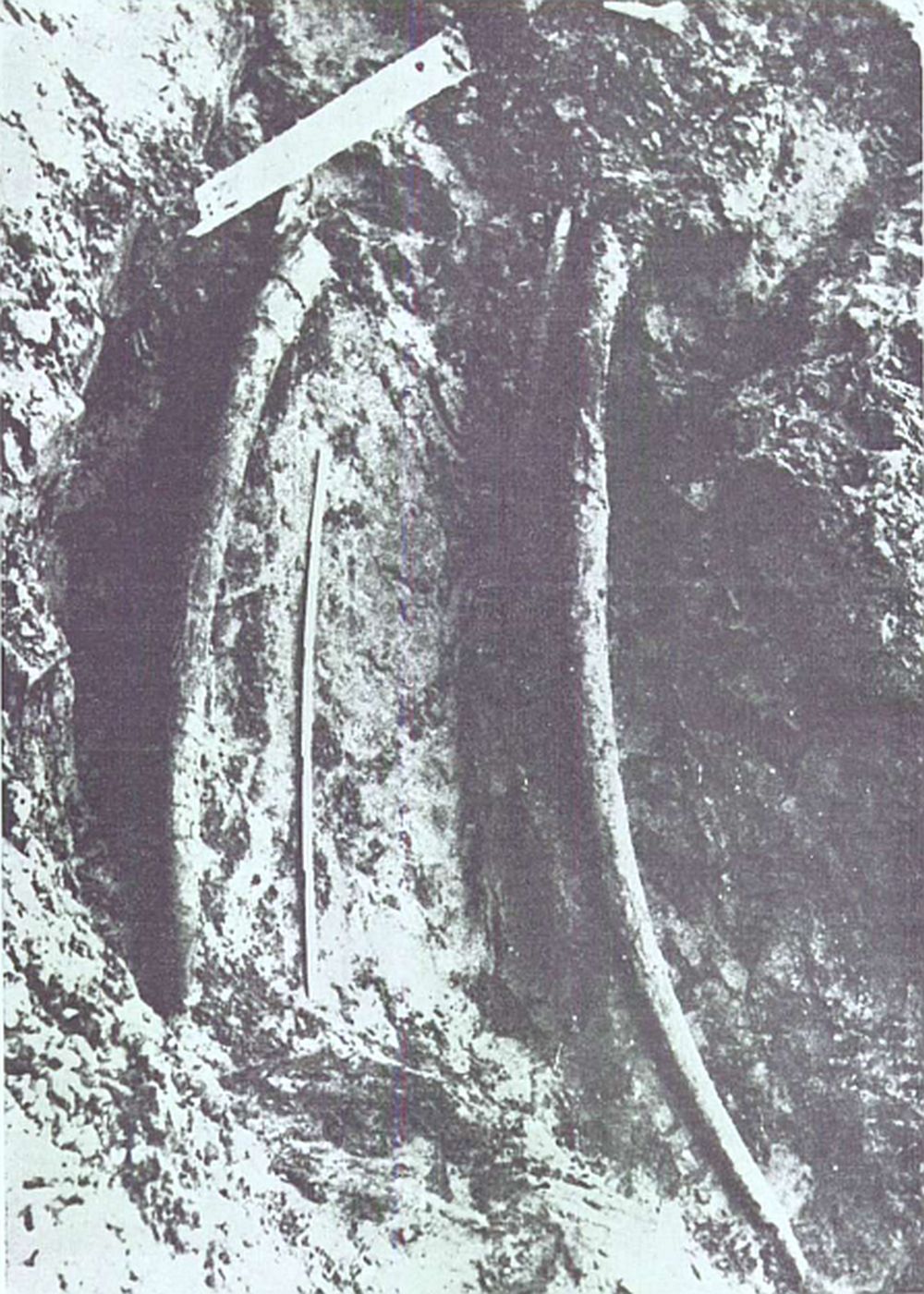

Sadnikar informed the museum workers about the finding, who immediately began with excavations. The digging lasted for about two weeks in an area of about 180 square meters, and resulted in the finding of nearly an entire skeleton of an exceptionally large male mammoth, a tusk measuring 2.7 meters in length.

The mammoth, 40 years old when it died, was most probably killed by Stone Age hunters, who also left behind some of the tools and probably broke into the skull of the animal to get at the soft tissue inside in search for food, which is why the skeleton is missing some skull bone.

Although findings of tusks and parts of mammoth bones are relatively common, whole skeletons are not. The mammoth’s bones are now exhibited in the Slovenian Museum of Natural History.

Mammoths, however, were not the oldest elephant-like creatures whose presence has been confirmed by excavations. Since the late 19 century, several findings have proven that several much older species stomped these lands, known under a common name of mastodon.

In 1871 a whole mastodon skeleton was found near Ljutomer, but it fell apart during excavation. In 1888 parts of a head and skeleton of the species called Tapirus hungaricus H. v Mayer were found in Šaleška dolina.

In 1890 a fragment of a tooth was found in Velenje, and other small fragments were also found near Radgona, and near Slovenska Bistrica in 1942. After the war, fragments of mastodon were also found near Slovenske Gorice and Čentibske Gorice, and finally, in 1964 in Škale near Velenje, where four mastodon sites were discovered.

The most interesting one consists of a skull with teeth and two tusks. The left tusk is 2.3 meters long and is completely preserved, including its root still stuck in the bone of the head.

From the findings they have identified three specimens of two different species of mastodon, who lived approximately 1.7 million years ago.

Mastodon’s lived much earlier than mammoths, they had a longer, stocky body and head and forward pointed tusks.

Mastodon remains are exhibited at Velenje Museum.

Source: Kladnik Darinka: Slovenija v zgodbah, Cankarjeva založba, Ljubljana, 2015

STA, 7 May 2019 - President Borut Pahor highlighted the "unforgettable symbolic and actual role" the May Declaration played for Slovenia's independence, as he hosted a reception to mark 30 years since the document calling for the country's sovereignty was read out at a mass rally in Ljubljana's Congress Square.

Since the declaration paved the way to Slovenia's independence, it deserves to have a permanent place in our collective memory, he said at the Presidential Palace on Tuesday.

"Its greatest value is linking democracy, sovereignty and Slovenia's place in an overhauled Europe, which also makes it important for the future."

Admitting that Slovenia would need to keep working on the three goals, he said "all three elements need our encouragement, criticism and debates, but also due cooperation and consensus".

V Predsedniški palači prva državna obeležitev 30. obletnice Majniške deklaracije 1989 za suvereno državo slovenskega naroda https://t.co/RJcLamqTsA pic.twitter.com/21KwDhqU6S

— Borut Pahor (@BorutPahor) May 7, 2019

"We decide on our own state and its democracy on our own, and on European future together with other nations," he said at the first-ever state-level event marking an anniversary of the reading of the 1989 declaration.

"Also today, 30 years on, it is clear that the sovereign Slovenian state, democratic and integrated into Europe, is the basic tool of our existence and development."

He recalled that the public legitimation of the idea about the sovereignty of the Slovenian nation had only been possible during the political spring in the late 1980s. "Before that, it was considered illegitimate."

Just like Dimitrij Rupel, a co-author of the declaration, Pahor stressed the 1989 events had led to the first democratic elections, a referendum on independence, decisions on Slovenia's independence and to the country's international recognition.

Outlining the conditions under which it was written, Rupel said the declaration came into being in his office at the Faculty of Sociology, Political Sciences and Journalism in April 1989.

Writer Tone Pavček was asked to read it "because the Slovenian Writers' Association was the first organisation signed under the declaration and because we did not want it to be interpreted as a manifesto belonging to any of the four [political] parties," said Rupel.

The declaration was also signed by the Slovenian Democratic Union (SDZ), the Slovenian Farmer's Union (SKZ), the Slovenian Christian and Social Movement (SKSG), the Socialdemocratic Union (SDZS), the university conference of the Socialist Youth League of Slovenia (ZSMS) and the Slovenian Composers' Association.

Its name was taken from the 1917 declaration in which Slovenian, Croatian and Serbian deputies demanded living in an autonomous unit within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The document was read in the Vienna parliament on 30 May 1917 by Slovenian deputy Anton Korošec.

The declaration reading led to independence, but the document would have been overlooked had it not become part of the Committee for the Protection of Human Rights' campaign for the release of all four dissidents from the JBTZ military trial, said Jožef Školč, the then president of the ZSMS.

Since neither the committee nor the ZSMS had a permit for the rally, the declaration was read at what was formally termed an open session of the ZSMS in Congress Square, Školč, who hosted an event on the occasion at the Museum of Contemporary History, told the STA.

"We simply took the risk of holding a session of the sociopolitical organisation and waited if anyone would dare ban it," said Školč, noting they had tried to express their frustration at the second arrest of Janez Janša, now the leader of the opposition Democrats (SDS).

Igor Bavčar, who led the committee, said, as he addressed the event at the museum, the events from 30 years ago were a reminder of what could be achieved with perseverance.

"That was a time full of emotions and unpredictability, of some realistic but often also imaginary dangers and disinformation.

"It became clear what we had avoided only after certain documents were discovered later on," he said, adding a new wave of arrests had been planned but had probably not taken place because of their activity.

Bavčar said the late 1980s and early 1990s had been a time of incredible enthusiasm which brought together people of different ideologies, which he sees as a special value.

Bavčar, who soon became interior minister and later led the Istrabenz conglomerate, is happy with the legacy of the May Declaration.

He is however less happy "with everything that has befallen me, and I'm still fighting against it," he said in reference to his serving a prison sentence for money laundering.

This week saw the 500th anniversary of Leonardo da Vinci’s death, with both scholarly and popular interest in the man and his work showing no sign of abating half a millennium after his passing. Among the many articles marking this occasion was one published by RTV Slovenia, in conjunction with a documentary shown by the national broadcaster, which added some local interest to the story of one of the original Renaissance men.

Da Vinci thus devised a plan that would prevent Turkish invasions of the Venetian Republic by using a system of dams and allowing the flooding of certain valleys, as well as designing a movable artillery defensive system in the Posočje region, and sketching a picture of the bridge over the Vipava River.

However, while the Atlantic Codex reveals that da Vinci undoubtedly visited and studied the confluence of the Vipava and Soča rivers, present-day Gorica, and surrounding areas, his plans for the building of a Venetian defensive line remained, like so many of his ideas and inventions, unrealised.

STA, 28 April 2019 - Vinica, a tiny border town in the south-east, is marking the centenary of a republic (Viniška republika) declared on its territory on 21 April 1919 but repressed only three days later.

Vinica residents got the idea to declare an independent state, the Republic of Vinica, from local survivors of World War I (1914-1918).

The cause for declaring it was problems surrounding the stamping of money, which caused a stir in this village in the Bela Krajina region, prompting secession.

The rebellion was repressed by the police and army of the State of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which emerged after the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in late 1918.

President Borut Pahor, the keynote speaker at Saturday's main event, said Slovenians should proudly remember everything that had made them a sovereign nation which cherished the spirit of resistance.

Pointing to the 27 April Resistance Day, he said it was people's resistance that this public holiday and the celebrations of the Vinica Republic centenary had in common.

The people of Vinica had a sincere wish to choose their own representatives, he said, adding that such great ideas deserved admiration.

Pahor noted the Republic of Vinica was one of many events proving the idea of a democratic and sovereign Slovenia had not happened overnight but was a result of efforts of many generations.

As part of five-day centenary celebrations, a screening of a documentary on the Republic of Vinica made in 2012 by public broadcaster RTV Slovenija is scheduled for Tuesday alongside a workshop on Vinica postcards to be held at the house in which writer Oton Župančič (1878-1949), Vinica's most famous resident, was born.

April 28, 2019

Money in Slovenia has existed in three different currencies since the country declared independence on June 26, 1991, the last one being the euro, introduced on January 1, 2007.

Before the euro, the Slovenian currency was the tolar.

And before the tolar, Slovenia used the Yugoslavian dinar.

The dinar was a troubled currency that went through several periods of hyperinflation, each one leading to a revaluation. From the mid-1980s on, the devaluation of money also started to affect the aesthetic value of the banknotes.

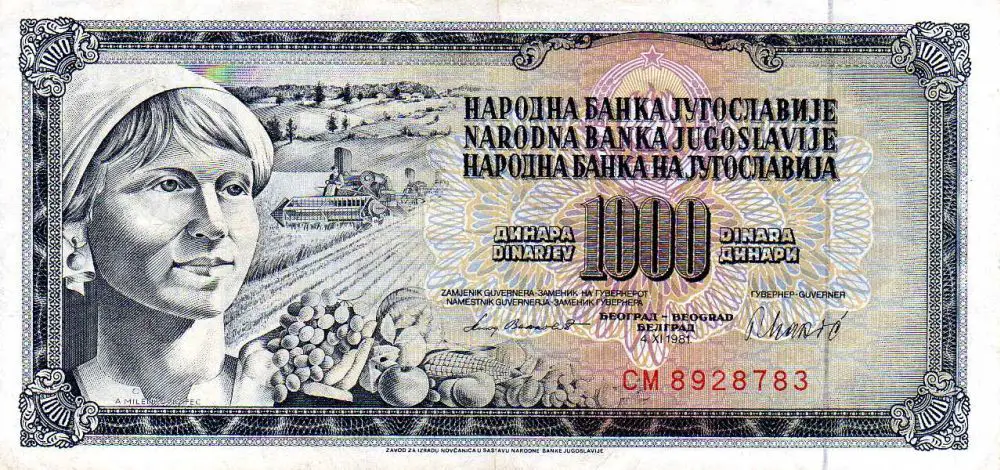

Shown below are the designs of banknotes following the first revaluation of the dinar in 1965, which were in use for about 20 years.

These banknotes were relatively detailed in design, depicted anonymous workers or statues and only changed slightly over time, mostly to update the font or background details depicting the nominal value. The 500 dinar note with Nikola Tesla was introduced in 1970 and another one, a 1,000 dinar bill, was introduced in 1974. This was also the last note designed in the old classic style of dinar, when it was still worth anything.

In about 1980 I was considered old enough to be given some change and sent downtown to buy my own ice cream. In a few years of this independent ice cream consumption, I started to observe a pattern; each new summer season the price of a scoop of ice-cream doubled. I found that quite handy as I could enter the new season prepared. Until one day the whole thing became unpredictable.

Changing money in Slovenia

That actually happened around 1985, when strange ugly money started to enter circulation. To encourage people’s trust into these notes, Tito’s face was put on the first one of them.

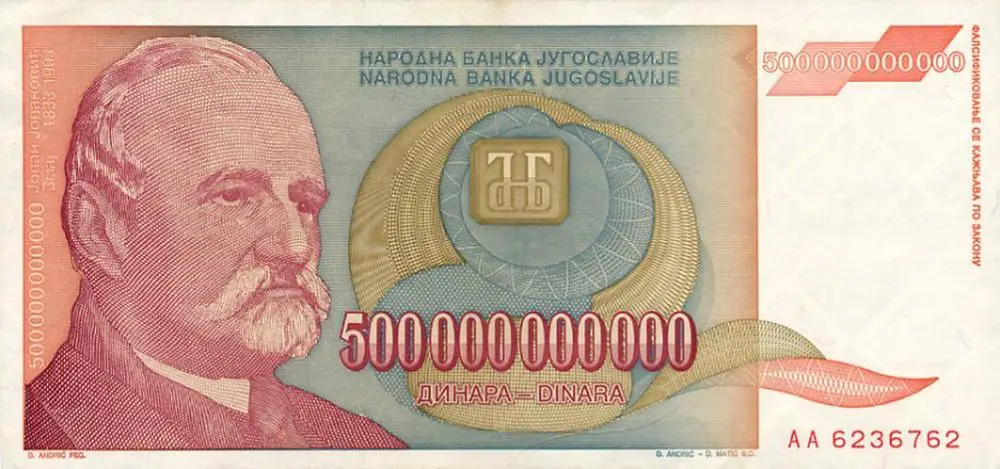

The Tito 5,000 dinar note was issued in 1985, the 20,000 bill in 1987, 50,000 in 1988, and the remaining four including the last one, the 2,000,000 dinar bill, all came out in 1989.

It seemed that money was devaluing faster than the central bank designers could draw.

The second revaluation took place on January 1st, 1990 with a new “convertible dinar” set at 10,000 : 1, basically cutting four zeros off, and from then on a whole devaluation spiral could continue.

When the 5,000 bill was introduced in 1991, featuring the Yugoslavian Nobel Laureate for literature, Ivo Andrić, the country was coming to an end. This was the last dinar with writing in different languages inscribed on it, and the last one with the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia coat of arms.

Slovenian currency, a short-lived experiment

On October 8 1991 Slovenia switched to the tolar, on December 23 Croatia introduced the Croatian dinar, on April 26 1992 Macedonia adopted the Macedonian denar, and on July 1 1992 Bosnia and Hercegovina switched to the Bosnian dinar. This was also the date of the Yugoslavian dinar’s third revaluation and the beginning of a period of massive hyperinflation, which at its peak in January 1994 amounted to 313 million % monthly inflation, meaning that prices would double every two or three days.

Although Slobodan Milošević blamed this monetary fiasco on sanctions imposed on what was left of Yugoslavia by the United Nations in response to Bosnian War in 1992, earlier events suggest that this time of hyperinflation might have been mostly to his own destruction of economy in his attempt at securing power. As the Federal government’s Prime Minister Ante Marković figured out as early as on January 7th 1991, the Serbian parliament secretly ordered the Serbian National Bank to issue US$1.4 billion in credit to Milošević’s friends and political supporters. This illegal plundering of the state equaled more than half of all the new money the National Bank of Yugoslavia had planned to create in 1991.

The Yugoslavian hyperinflation of 1993/94 was at the time the second highest ever recorded, until Zimbabwe pushed it to third place in 2008. The absolute winner remains the Hungarian pengő in 1946. This peaked at 1.3 x 1016 percent per month (prices double every 15 hours), and when the forint replaced the pengő in 1946, the total value of all notes in circulation in Hungary amounted to 1/1000 of one American dollar.

STA, 25 April 2019 - Paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, photographs and films created by more than 130 authors between 1929 and 1941 in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia will be displayed at the Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana until 15 September, 2019.

On the Brink: The Visual Arts in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929-1941) provides an overview of the visual art from the start of the reign of King Alexander I on 6 January 1929 to the beginning of World War II in Yugoslavia in April 1941.

Divided into five sections, it deals with five topics through different works of art and presentations. The show, the gallery's most ambitious event this year, will be accompanied by more than 20 film screenings.

In the section exploring intimacy and the inner world, works by major Serbian and Slovenian painters are put on show, the second section is dedicated to landscapes.

The third section, focussing on contrasts, is the central part of the exhibition and features a painting by Serbian Petar Dobrović depicting journalists of the Danas magazine.

It also presents a clash on the left between Croatian writer Miroslav Krleža and Marko Ristić, a representative of Belgrade's surrealism.

The fourth section is dubbed People. According to curator Marko Jenko, this room is very chaotic, presenting people from cities and the countryside, mainly through reportage photography, which was very popular at the time.

The final part of the exhibition presents Yugoslavia's ties between the two world wars through the first two official presentations of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia at the Venice Biennale in 1938 and 1940.

According to Moderna Galerija director Zdenka Badovinac, the historical context of the period is presented through excerpts from a 1934 travelogue by Louis Adamič, The Native's Return.

Slovenian-US writer Adamič presented the complex situation in the kingdom at the time through his encounters with a variety of people, including Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović, Dobrović and Krleža.

He was also received by King Alexander I, one year before his assassination in Marseilles.

Adamič portrayed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia as a country on the brink, a country of stark contrasts, caught between old, premodern customs and the grip of capitalism, with a premonition of its imminent end in a broader European and global context, the museum of modern art says.

The exhibition is open until 15 September.

April 17, 2019

In 1937 the Slovenian Communist Party was established in Čebine above Trbovlje as a formal implementation of a decision adopted at the fourth meeting of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in 1934.

Revolutionary fever, which gained momentum during WWI, continued among demobilised farmers and workers with several rebellions and even attempts at establishing Soviet Republics in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between the years 2018-19.

The Slovenian Communist Party was first established in 1920, but lost independence a month later after merging with the Yugoslav Communist Party. It adopted a thesis of one Yugoslav nation composed of three tribes, the revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat as its goal.

In 1920 communist activity was banned by a decree, and a year later completely pushed into the underground following a few notable assassinations that were ascribed to communists.

In early 1930 young Russian educated communists such as Boris Kidrič and Edvard Kardelj begun a communist revival in Slovenia. In December 1934 the Communist Party of Yugoslavia held a congress in Ljubljana where a conclusion was adopted to establish Communist Parties of Slovenia and Croatia, but also Macedonia in the future – under the clear condition that the Communist Party of Yugoslavia would remain unified and centralised. This was finally implemented in 1937, mostly due to low numbers of communists in the country in 1934.

The ideological background of the Party in early the 30s was vague and addressed little to none of the pressing questions of the day. Clearer goals were then recognised on the Communist International in Moscow in the summer of 1935, which established fascism as the main enemy of communism, the people and nations as such, and which also allowed petit bourgeoisie to join the revolutionary struggle.

In this context of a polity of a People's Front against all forms of fascism, the Slovenian Communist Party was secretly established on April 17, 1937, with Edvard Kardelj as its leader. When in the same year Josip Broz Tito took the leadership of the Yugoslavian Communist Party, three of the Slovenian communist leaders were included into its leadership: Edvard Kardelj, Franc Leskošek and Miha Marinko.

The People's Front policy concluded two years later with the Ribbentropp-Molotov pact, between Stalin and Hitler, which prompted several early Slovenian communists such as Angela Vode, to leave the Party, while the remainder of the leadership decided to bow to Moscow. In the next two years the Slovenian Communist Party softened its anti-fascist propaganda and replaced it with a struggle against “Western imperialists” instead.

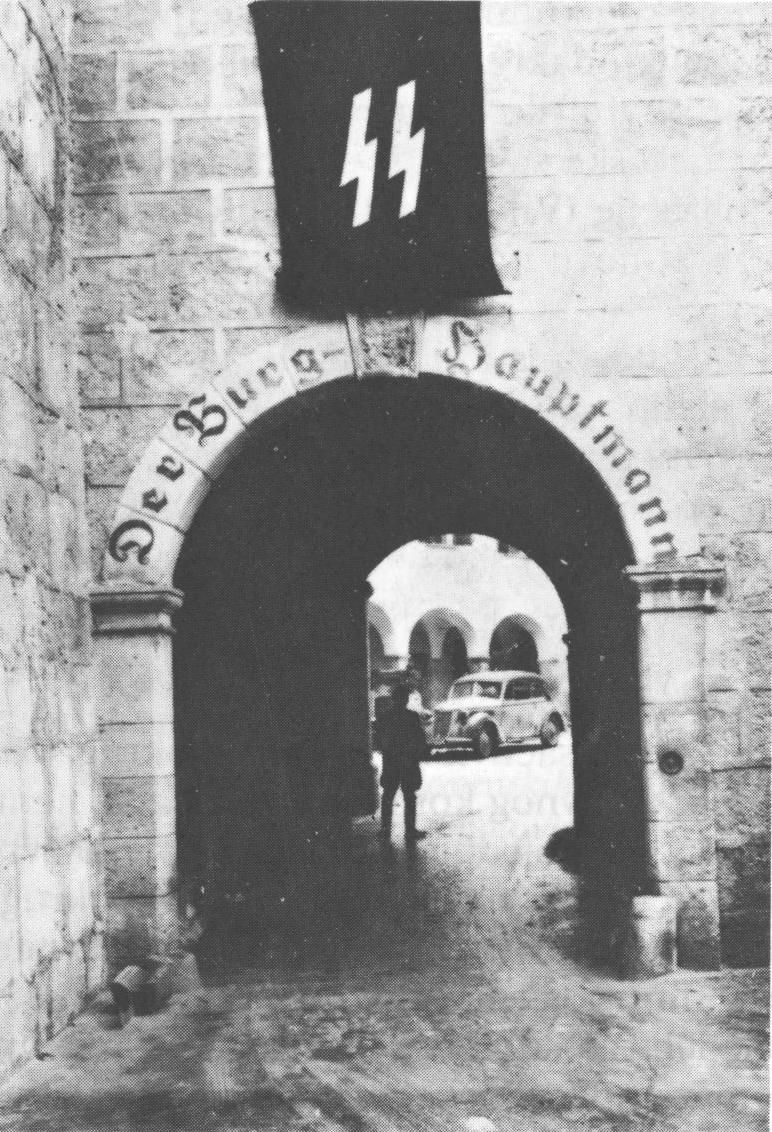

April 1941 saw the invasion of Slovenia by Germany, Italy and Hungary, as noted here. April 26 then saw the visit of Hitler to Maribor, or Marburg an der Drau , as he knew it. That story was told in more detail in an earlier article, and in this one we’ll simply be presenting of the striking images and film footage we came across while doing some related research, showing Nazis in Slovenia.

German soliders crossing from Austria into Slovenia, entering Maribor

Hitler in Maribor

Hitler, and other Nazis, meeting an ethnic German (Volksdeutsche) in Maribor

Volksdeutsche in Maribor

Himmler in Maribor

Nazi headquarters in Maribor

German soldiers on Maribor ulica

The entrance to Castle Brestanica (Grad Rajhenburg)

Volksdeutsche in Celje

Celje

Celje

Nazi officials in Bled

Finally, here's a train ride from 1941, with much of it in Slovenia

STA, 13 April 2019 - President Borut Pahor and US congressman Paul A. Gosar honoured eight crew members of a downed US bomber, who lost their lives in a crash near Polzela (NE) during WWII, as keynote speakers at a ceremony on Saturday. The event also celebrated Slovenian-American Friendship and Alliance Day.

Pahor marked the 75th anniversary of the bomber's downing by laying a wreath at the memorial commemorating the crew members.

In his address, Pahor highlighted the long tradition of friendship between Slovenia and the US, adding that it also allowed for occasional differences in positions.

Tradicionalna slovesnost "Dan slovensko-ameriškega prijateljstva in zavezništva" v Andražu nad Polzelo. PRS je ob 75. obletnici strmoglavljenja ameriškega bombnika B-17 položil venec k spominski plošči v spomin osmim članom posadke, ki so ob tem izgubili življenje. pic.twitter.com/e0ftJQFMZT

— Borut Pahor (@BorutPahor) April 13, 2019

While the present US administration may perhaps not share the views of Slovenia and the EU, Pahor said that there was always a search for what unites us, as this was important both for Slovenia and the US.

Gosar, a Republican of Slovenian descent who is visiting Slovenia for an extended weekend at the invitation of the president, thanked Pahor on the warm reception he has received in Slovenia.

He argued that Slovenian generosity and courage had also been what had given hope and light to the downed US soldiers.

Gosar received the Golden Order of Merit, one of Slovenia's highest state decorations, on Friday, for his contribution and cooperation in strengthening relations between Slovenia and the US.

Gosar will also hold meetings with Slovenian officials to further strengthen the relationship between the two countries on Monday.

The congressman recently established the House of Representatives Friends of Slovenia Caucus, which he is to co-chair.

The US bomber B-17 flew from an Italian military base along with other 233 combat aircraft and was headed toward the Austrian Carinthia to bomb the Steyer factory, which was contributing to the German military industry at the time. It was shot down at the Andraž settlement near Polzela on 19 March in 1944.

Eight crew members died in the crash, while two of them were taken as prisoners of war and survived in POW camps. The crew members belonged to the 15th US Air Force division.