Ljubljana related

January 22, 2019

It is said that every true Slovene should climb to the top of Triglav, the highest Slovenian mountain, at least once in their lifetime.

However, recent reports of heavy traffic at the top of the mountain along with the trash trail that follows it are evidence that such an expression of national pride doesn’t come without the cost these days. Calls to drop the ‘everyone on Triglav’ idea and replace it with practices that are focused on preservation of nature rather than the defence of territory by repeated conquests of inhabitable lands have been becoming louder in the last two decades. Such a paradigm change is even more pressing since the struggle for independence ended with the final acquisition of the Slovenian statehood in 1991.

This article, however is not about what should be done about mass tourism at the top of Slovenia’s highest peak, but rather how it has all begun. How and why did Triglav and mountaineering in general become so tightly knitted into the fabric of the Slovenian national identity.

The start of an obsession

“To conquer the summit” is in fact a literal translation of a Slovenian expression for reaching the summit (osvojiti vrh), while the very idea of climbing to the top of a mountain instead of worshipping it from the bottom originates in the ideas of the Enlightenment.

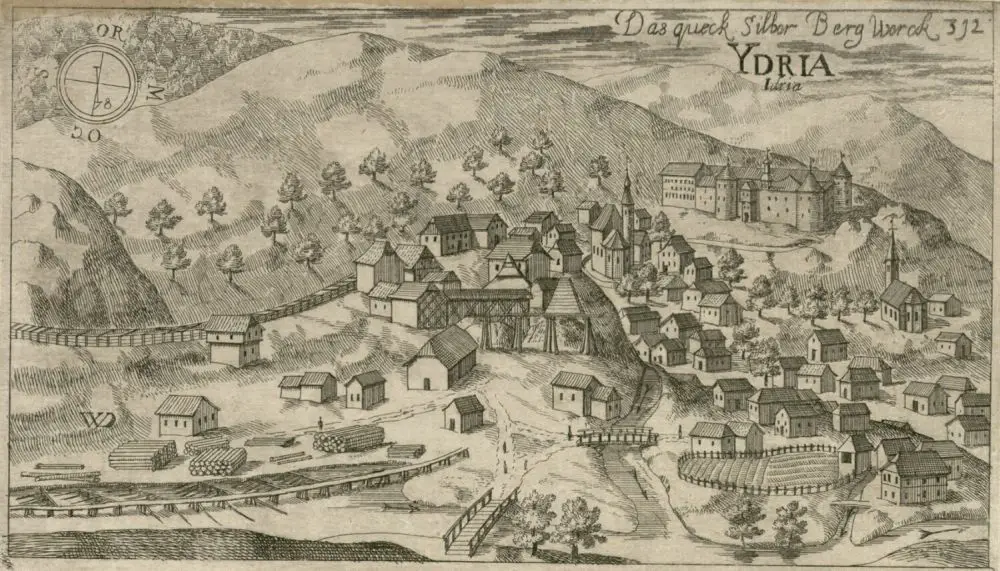

One of the most important places which allowed for the enlightenment to spread among the 18th century Slovenes was, perhaps surprising for some, a secluded mining town called Idrija, the location of the world’s second largest mercury mine. As such, Idrija attracted some of the Europe’s finest natural scientists of the time, in particular Giovanni Antonio Scopoli and Balthasar Hacquet. And both men played an important role in the series of events that lead to the first reaching of Triglav’s summit in 1778, which took place eight years before Mont Blanc, the highest peak in the Alps, was climbed.

Now, Triglav at the time was not Triglav today, equipped with ropes, iron fences and widened trails, and even though the peak lies below three thousand metres, it was quite a difficult mountain to climb, not something one could do on the first attempt. So how did the two enlightened thinkers influence the idea to get to the top?

Scopoli, born in the Southern Tirol (today’s Italy) of the Hapsburg Empire, served in Idrija as the first mine physician between 1754 and 1769, a job which included extensive research on the surrounding botany (no antibiotics in those days), including the Julian Alps, the location of the Triglav massive. This is why Scopoli ended as the first man at the top of Storžič (2,132m) in 1758 and Grintavec (2,558m) in 1759. In 1760 Scopoli published a book on his findings called Flora Carniolica and kept a regular correspondence with no other but the father of contemporary taxonomy, Carl von Linné (aka Carl Linnaeus) in Sweden. The two communicated in Latin.

Apart from his inventory of over 1,100 plants from the Slovenian Northwest, Scopoli also founded an education programme in metallurgy and chemistry in Idrija, which he eventually left for professor’s position at several respectable universities in central Europe.

In Idrija, Scopoli was joined and then replaced by a French surgeon and natural scientist Balthasar Hacquet, who, intrigued by Scopoli’s work, came to Idrija in 1766. Hacquet, also credited with the first description of mercury poisoning symptoms, followed in Scopoli’s steps and attempted his first ascent to Triglav in 1777, but only reached one of the mountain’s lower peaks, Mali Triglav.

The natural sciences and Žiga Zois

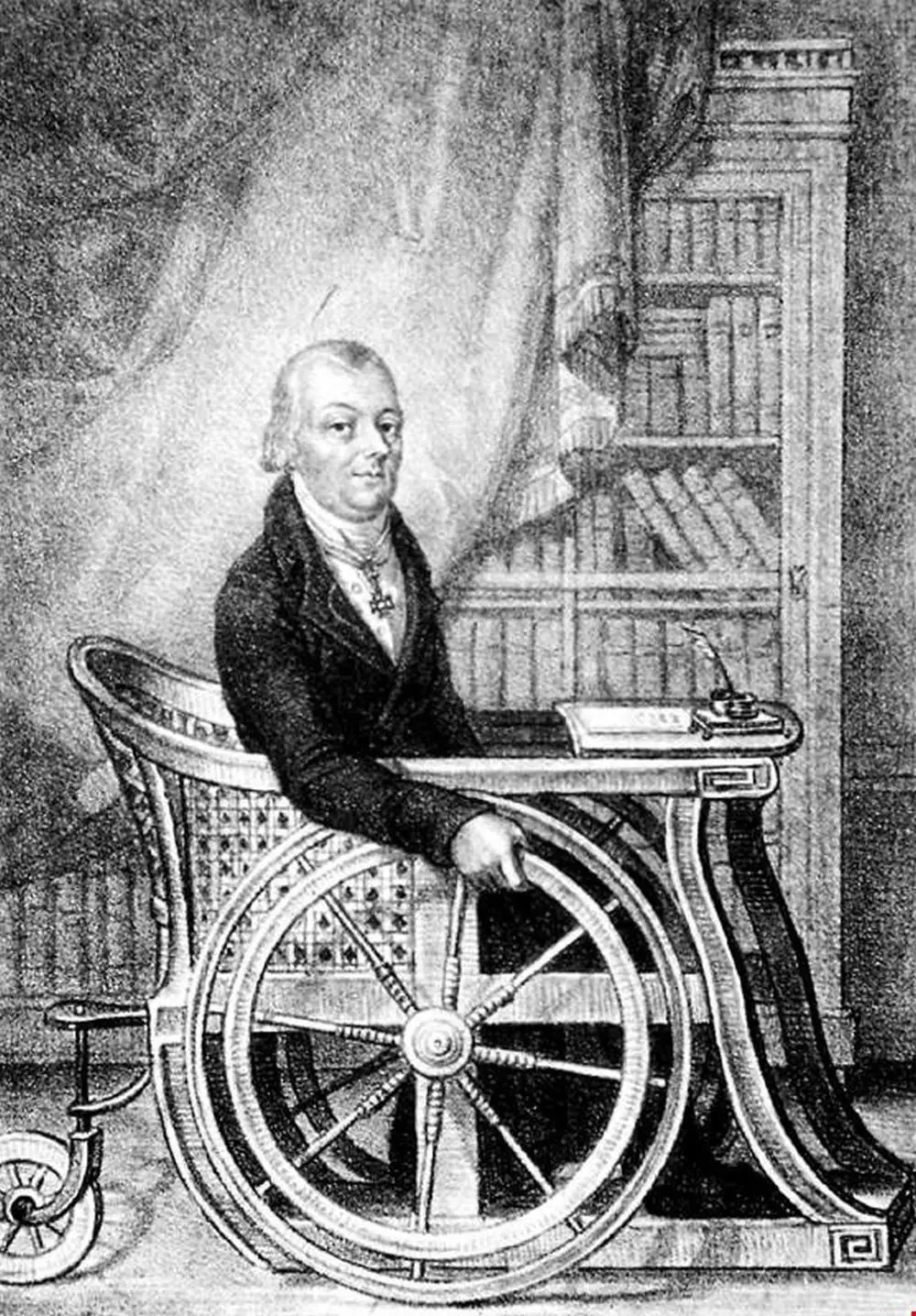

At the time Hacquet was also in correspondence with Žiga Zois (Sigmund Zois), a natural science enthusiast, geologist and at the time the richest Slovene, who had just purchased an ironworks facility (fužina) at the foot of the mountain in Bohinj.

Why Sigismund (Žiga) Zois decided to sponsor the first expedition to the top of Triglav in 1778 is not entirely clear, as the so-called Bohinj papers in which expedition details were discussed have been lost. According to one theory, the predominant reasons were to send someone on the lookout for possible new ore deposits. Another theory is that Zois got inspired by the failed attempt of his geologist pen-pal Hacquet. Either way, Žiga Zois presumably promised a financial award to anyone reaching the top and also organised an expedition, which eventually successfully reached the summit for the first time in 1778.

The expedition was led by Zois’ ironworks facility physician and Hacquet’s student Lawrence Willomitzer, who was to be accompanied by three local guides: Luka Korošec and Matevž Kos, both miners and a hunter Štefan Rožič. Although there is some debate about wether or not all of the men really reached the top, in 1978 the Mountaineering Association decided to depict all four men in a statue in Ribčev Laz, Bohinj, as “more first ascents are better than less”.

Vodnik makes it to the top of Slovenia

Besides researchers and the nobility (Žiga Zois was a baron), another group of people was interested in mountaineering in those early days: priests.

The first one to mention is Valentin Vodnik from Šiška (Ljubljana), who went to Triglav in 1795 in another of the expeditions financed by Zois. The main goal was to prove the neptunist theory on the sea origin of Julian rocks, and thereby refute the plutonist claims of the rock’s volcanic origin, a dispute Zois found himself in with an acquaintance from Transylvania, Johann Ehrenreich von Fichtel, whose claims on the upper parts of the mountain to be of volcanic origin were based on a simple assumption. To prove Fichtel wrong Zois needed a specimen from the top of the mountain that would show some sediment, which was eventually provided by Vodnik.

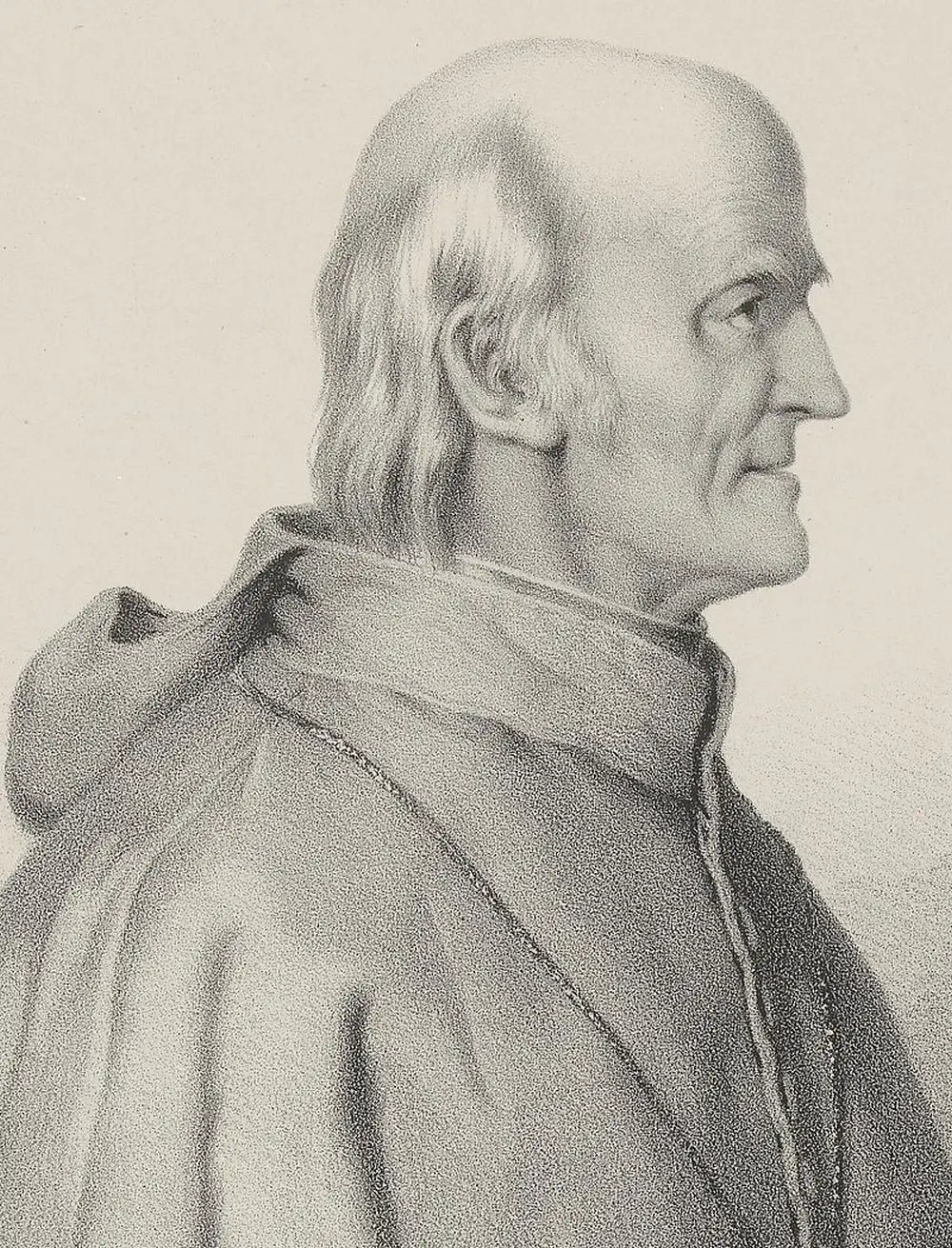

Valentin Vodnik, however, didn’t stay priest much longer after meeting Zois in 1792. He switched to teaching position at Ljubljana grammar school six years later. As such, both Vodnik and his patron Zois are part of the group responsible for the early experimentations with Slovenian nationalism, which in the case of Valentin Vodnik meant the use of what was then considered vulgar peasant language in poetry. Indeed, Vodnik’s 1794 ascent of Kredarica and then a year later of Triglav inspired one of his better poems, Vršac.

With Austria’s defeat by the Napoleon’s army, life changed significantly for Vodnik in 1809, when the newly established Illyrian province with its capital set in Ljubljana allowed him to teach in the Slovenian language. He became a principal of Ljubljana grammar school and a supervisor of vocational and handicraft schools. Vodnik marked this French move in support of local ethnic empowerment with an ode called “Illyria reborn” (published in 1811), for which he had to pay a price once the Austrians took their territory back in 1813 – he was banned from ever teaching again in 1815.

Alpinism evolves

In this circle of early priest alpinists we can also count the Dežman brothers, who also reached the top of Triglav in the years of 1808 and 1809. Among Slovenia’s most notable alpine climbers at the time, however, Valentin Stanič stands out as the first proper alpinist in a contemporary sense of the word. His ascents were often unique and daring, since he regularly climbed solo without a guide and even in winter time. He climbed various European mountains, including Grossglockner in 1800. In 1808 he and his guide Anton Kos reached the top of Triglav, where Stanič measured its altitude with a barometric device and only missed the exact figure by 7 metres, an admirable result for an amateur surveyor. Although it seems that his climbing initially served his scientific interests, Stanič later developed a much more sporting interest in trying to climb as many mountains as possible, to be the first one to reach unconquered summits, and on the way overcome hardships and experience happiness and excitement, attitudes that were very unusual and forward-thinking for the era he climbed in.

Despite this, most researchers, noblemen and priests would not head into dangerous mountain conditions without local guides, with this latter group less concerned with getting to the top of the mountain than they were with the opportunity to make some money for themselves and their families.

Enter the Slavs

In the middle of the 19th century several ideological attitudes developed in the mountaineering communities of Europe.

The sporty style of the British nobility on Europe’s most prominent mountains came into being with the help of local French and Swiss guides. This elitist style of climbing by a leisure class who could afford to travel abroad and mount expeditions was contrasted by the style of the Germans, who were climbing at home and thus needed less money to do so, and for whom mountaineering was less associated with class, prestige and conquest. Well, until the Slavs enter the picture.

For most of the Slavs, and especially the Slovenes, mountaineering was closely associated with a defence against language- and class-related Germanising influences, as seen, for example, in the use of new German names for mountains and other places that were originally in Slovenian, a process that increased with the growing number of well-organised German climbing groups who were visiting the Julian Alps at the time. On top of this, Napoleon’s short-lived Illyrian province, which planted the seed of nationalistic sentiment in the minds of the Slovenian masses, strengthened the assimilating pressures of the Austrian empire, which in turn generated much greater resistance. Mountaineering thus became part of the Slovenian national project, and Triglav as the highest peak in the Julian Alps was its symbol.

Read part two here

January 16, 2019

In 1895 a decree of the City of Vienna limited the permitted worktime on Sundays to six hours, sparking protest from Slovenian chestnut sellers.

One of the oldest forms of seasonal work migration among Slovenes is that of selling chestnuts, with people moving at the beginning of winter to Vienna to roast chestnuts in the streets of the empire's capital.

In the 1850s there were about one thousand registered chestnut sellers in Vienna, out of which almost one half were from Slovenia, mostly from the areas of Velike Lašče, Ribnica and Kočevje. Chestnut huts were not known in those days, and kostanjarji would roast their chestnuts in the streets and markets from morning to night, no matter the weather.

On today's date in 1895 the City of Vienna limited all forms of work to six hours on Sunday to enforce observation of the Sabbath as a day reserved for rest and religious activity. This brought complaints from the chestnut sellers, as sales were best on Sundays. The authorities, however, insisted on the shortened hours and only allowed for extensions on the last Sunday before Christmas and in Prater, a large public park in Vienna.

At the end of the season Slovenian kostanjarji mostly returned to their homes, while some remained in the city. The latter were mostly from the Ribnica region, who established handicraft shops In Vienna and would continue their business selling their woodcraft items, also called suha roba (lit. ‘dry goods’) in the streets and markets of Vienna for the rest of the year.

"What are you doing?"

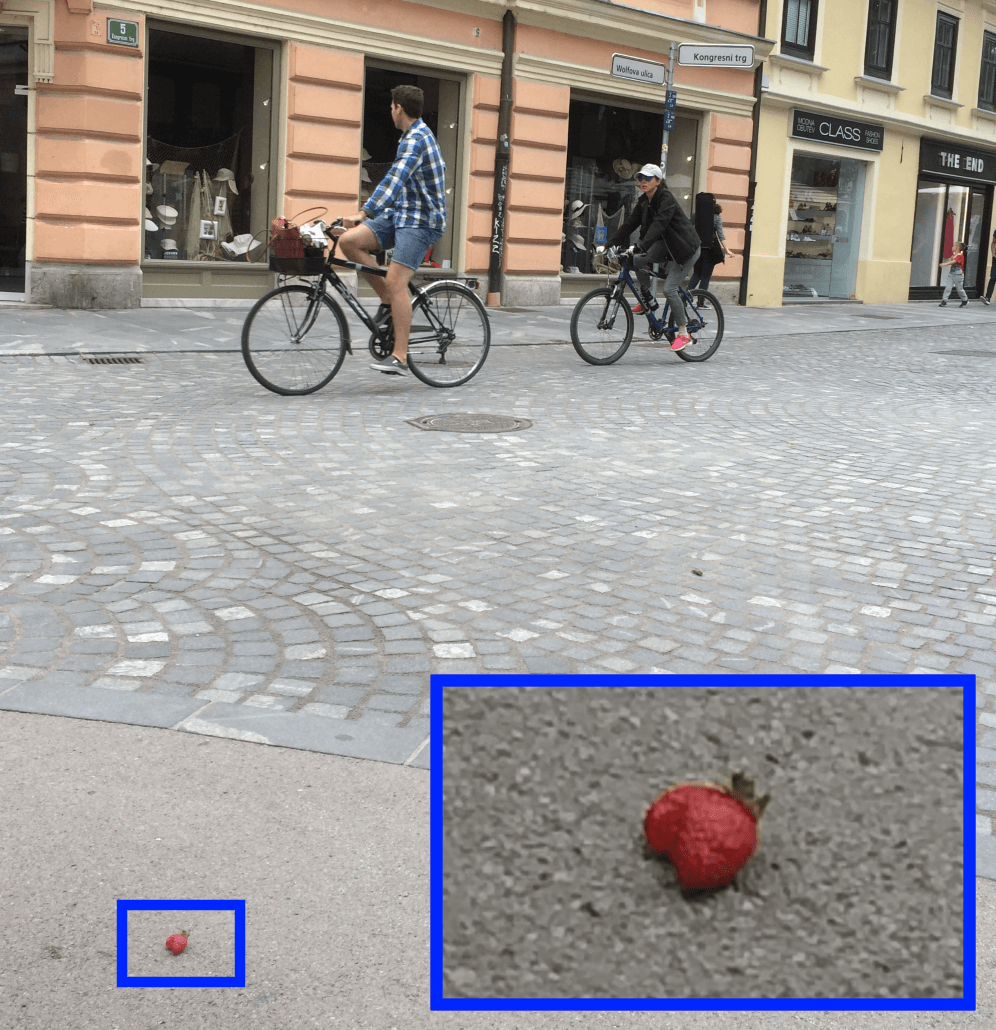

Kate was wondering why I was staring at the sidewalk as we sipped wine at Zvezda on Congress Square.

"That strawberry," I told her, likely slipped off someone's dessert at the cafe. I said I was calculating how long it would be before it was stepped on in the summertime, near-constant pedestrian stream. Given fastidious and careful-stepping Slovenes, I figured it stood a good chance of remaining intact.

The berry in question

The strawberry scene unfolded during our most recent Ljubljana sojourn, an intermittent story that began in 1991. Tank traps, troops and tension we saw back then at Congress Square, across from Zvezda, are long gone, replaced by the EU, the Euro and stability.

Tank traps in Congress Square, 1991 (Kongresni trg)

Slovenia, mostly unknown then, is now a world destination, attracting ever-growing numbers of visitors, to Bled, Ljubljana, and a slice of the Adriatic. But we worried on this trip, perhaps even facing the dismal prospect of being overwhelmed.

In 1997, I returned to study Slovene, and saw some early changes. In my notebook, I fretted then whether Slovenia could "survive the onslaught of western 'civilization,'" EU membership, and maintain historic links to the Balkans, and their once-fellow Yugoslav citizens. The "fragile beauty and rhythm of the 'club'," which I felt strongly in cozy Ljubljana, could be easily shattered, I wrote, two decades ago.

A time before "I feel Slovenia" - "Why should the Europeans have this terrific little secet all to themselves?"

Now, with Slovenia on the map, that seductive "I Feel Slovenia" slogan has worked all too well, no need to be lured. (It came as little surprise that as I finished writing this, Slovenia announced record tourist visits in 2018.) But what is the breaking point? Does a Venice or Amsterdam loom for Ljubljana, and maybe Slovenia, inundated by tourist waves, upending what they had come to experience?

This year, we came in June for three months, my first time as a citizen of Slovenia. Citizenship in the "old country" had always seemed like a crazy pipe dream. But in 2014 I applied, assembling roots records, my multiple newspaper accounts about our repeated visits, and assisted by a Ljubljana friend, a retired lawyer.

All four of my grandparents — John Puc and Johanna Starman, and John Krze and Frances Lustick — migrated a century-plus ago to Rock Springs, an unlikely multi-ethnic, coal-mining town in the high, cold desert of southern Wyoming USA, where I grew up in a sort-of Slovenian enclave. My mother made potica, we bought kisla repa from another family, and kranjska klobasa made by a Slovenian guy who also operated a highway motel. We never missed the yearly "grape festival" at the Slovenski Dom, and one fall Sunday everyone in the family joined my blacksmith grandfather in his basement to grind grapes, shipped to local Slovenes from California.

Slovenski Dom, Rock Springs, Wyoming, in 2011. Photo: Yurivict, GNU Free Documentation License

I wrote in my application that I considered citizenship to be fulfilling the dream of one of my grandmothers, who never learned English, always feeling, or so I thought, that one day she'd return to her beloved green Slovenia, leaving that dusty Wyoming desert behind.

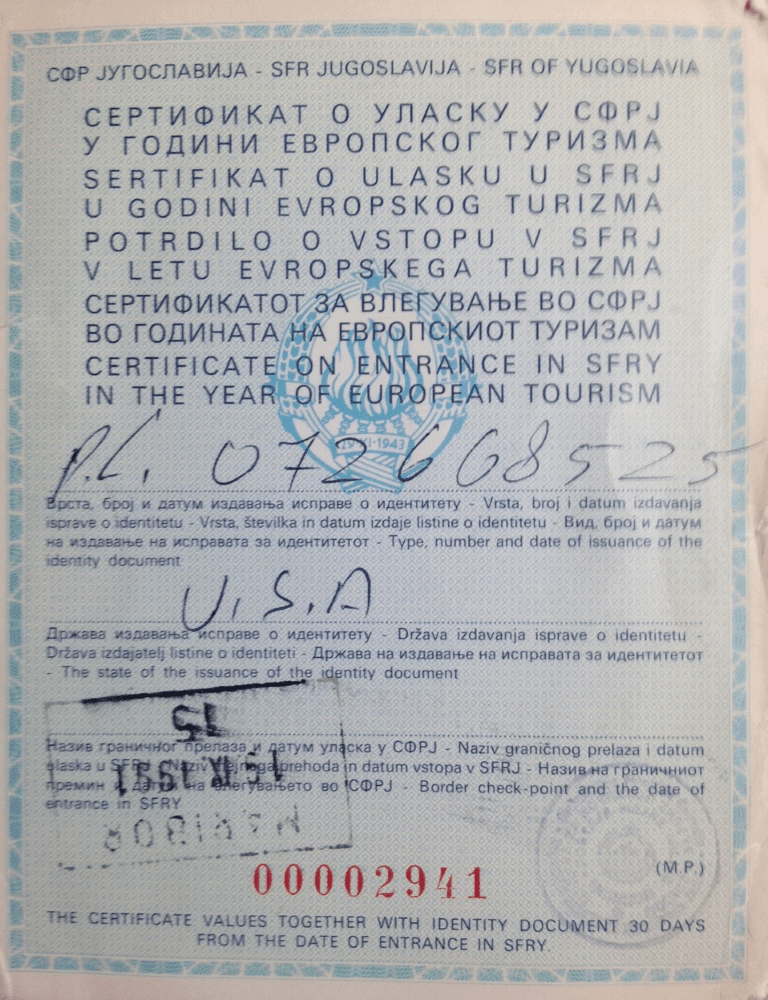

Travel documents from 1991

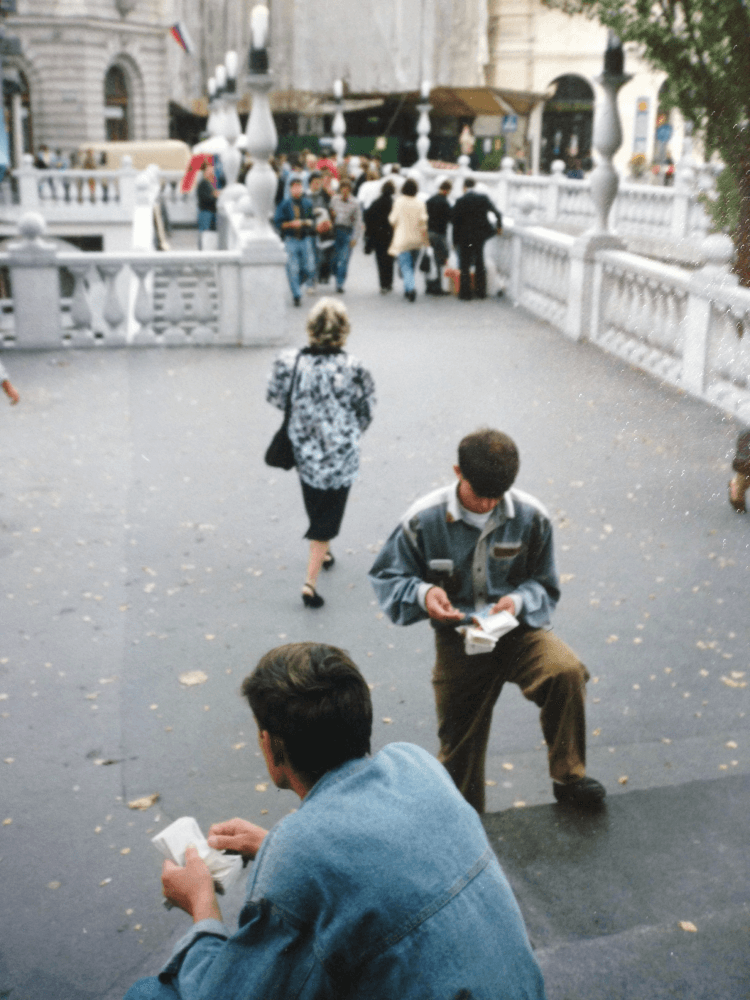

Back in early 1991, when we had planned our first visit, it was still Yugoslavia. But when we arrived in September, although border guards were handing out SFRY (Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) "certificates" for travel, almost overnight it had become Slovenia. Despite independence, there was uneasiness. Our friend Stanislav Fortuna stashed gas masks under the couch, at the ready. By the Triple Bridge, currency sellers hawked newly minted Slovenian tolars, beneath Prešeren's statue. The old-line department store, Centromerkur, was still in business (that's where we purchased material Kate only recently used to make kitchen curtains in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where we now reside in the USA). Titova Cesta, the main drag, was virtually empty late nights.

Currency sellers in Prešeren, 1991

That's all a distant memory. Centromerkur has vanished, replaced by the trendy Galerija Emporium. No longer is curtain material made in Slovenia, — no, our seller told us this year — all textiles are from Italy.

On the streets of Ljubljana, meanwhile, a more significant change: Increasingly more, and swifter, cars. Vehicle swarms unnerve bicyclists on narrow roadway bike lanes, so they opt for sidewalks. I call it "outsourcing danger," squeezing hapless pedestrians, forced to watch for oncoming and approaching bikes (and even motorcycles!) on what were sidewalks supposedly reserved for walkers. POZOR! That became our byword as pedestrians, which we are because we prefer foot, bus or train.

Bicyclists have also become more aggressive. They no longer "behave normally," Stanislav says. He's been riding bikes for nearly seven decades, he says, but now feels uncomfortable on the increasingly fast-paced streets.

Postcard of Town Square, 1969. Wikimedia, public domain

Postcard of Congress Square, 1969. Wikimedia, public domain

Also, less cars! It's a delight to walk the Triple Bridge, passed Prešeren, without dodging smoking autos and lumbering buses, the way we saw it in 1991. Tito's name has been scratched, and now Slovenska Cesta is off-limits to cars (mostly), for buses and walkers only. Now that's a refreshing change, promoting pedestrianism.

But bigger, better, faster — an unsavory USA import — has, alas, afflicted Ljubljana. Thankfully, pedestrian markings on streets still stop cars, though it's smart to glance left and right, just to be sure.

Surprisingly, there was little mention of Melania Trump, the Slovenian-born export to the USA, who left for bigger things and bright New York lights. The one-page In Your Pocket Guide writeup on Sevnica, her birthplace, doesn't even mention her. The only signs of Melania we saw were "first lady" products, tagged to fend off lawsuits she's filed to protect her name.

On the housing front, other changes. When I arrived in 1997 for language study, only three private rooms were for rent, one on Friskovec, where I stayed until relocating to a student dorm near Bezigrad. Now, hostels, hotels and Airbnbs abound, even in Mestni Trg, all of this giving neighborhoods a less-permanent feel.

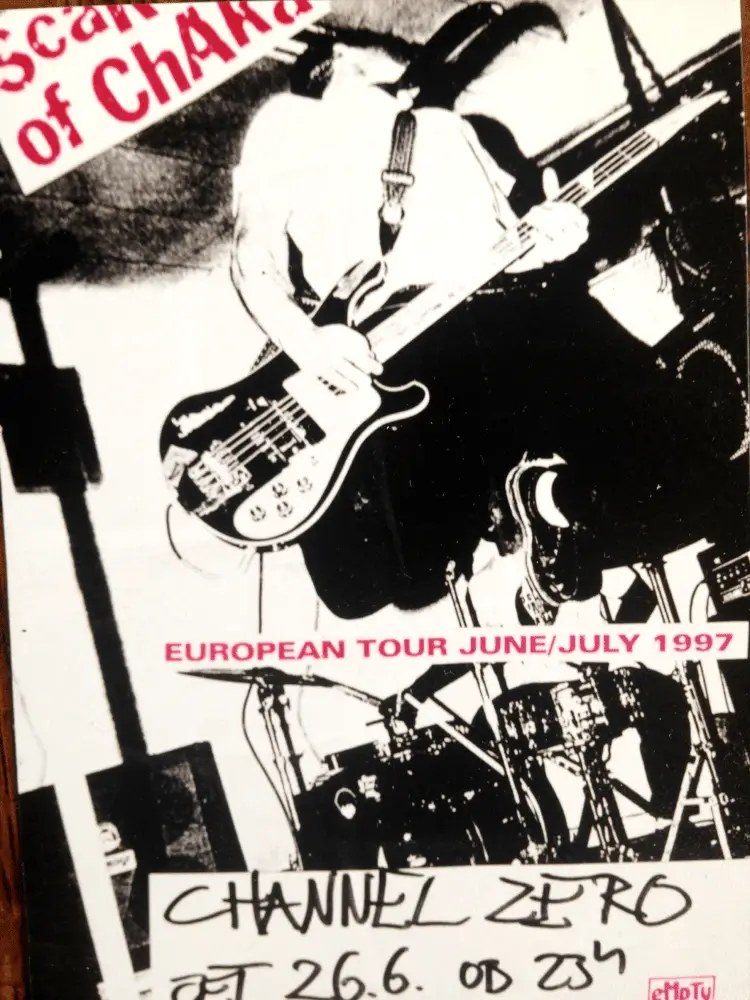

It was when I was at Friskovec that I found Metelkova, in its early raw stages, a time of honest energy and creativity. One late night I heard drums, and wondered what was up behind the walls on the street. The next night, I found out, through a newly opened hole, and happened upon Channel Zero, and a punk band passing through — Scared of Chaka, coincidentally, from Albuquerque, USA. I'm from Wyoming, I told a shocked Dave Hernandez, the band's frontman, who later formed a more widely popular USA band, The Shins.

A 2018 whirl through Metelkova left us feeling differently. Recent fires, a spat of sleazy characters milling about and police wandering around offered a different vibe. At Celica — an abandoned prison in 1997 — cordialness lingered, though one worker lamented that with the takeover by the company managing the Castle, a more mainstream and profit-oriented operation loomed.

Related: Celica - Former Prison, Hostel, & Full Artistic Experience in Ljubljana’s Metelkova

Down by Prešeren, other changes. By August, swelling tourist crowds intent on discovering "Europe's best-kept secret" noticeably thickened, at Trubarjeva, the Triple Bridge and the dragons. The crowded frenzy, unlike the 1990s and even latter-years Ljubljana, was amplified by street performers — a non-local mishmash of maddening, out-of-place bongos, incessant mandolins and disruptive break dancers. We longed for the Romani band that frequented the bridges, in 2014 and 2015, to feel that real Balkan beat, and felt sorry for the drowned-out, lone Slovenian accordionists cast into the sonic shadows.

To experience old-country spirit and heart, we left Ljubljana, for the out-of-the-way. By pure chance, we had met Sonja Bezjak at Carlos Pascual's "Pocket Teater." Even more fortunately, her home was near the Mura River in little-touristed northeast Slovenia, a region Kate by coincidence was reading about in Feri Lainscek's novel, Murisa.

Related: Slovenia's Foreign Entrepreneurs: Carlos Pascual, Working Writer

We drove with her to Ljutomer, where Slovenian language blossomed. Then, to Trate, her home, near an aging castle that housed mental patients where she and other volunteers established a "museum of madness," to focus on perceptions of mental health. We floated the Mura, and met stalwart river-protectors fending off misguided hydropower developers, an effort that's succeeded in getting UNESCO status for the river ecosystem.

Sonja's parents prepared a garden-fresh vegetable dinner, evoking that Slovenia past now receding all too quickly. It was all like a dream, I told them, recalling my grandparents' kitchen table in Rock Springs, my grandmother making lunch for my grandfather who walked from his blacksmith shop.

We returned, and lingered a bit longer in Ljubljana, lamenting our impending departure. One of our last stops was at Zvezda, and my strawberry watch. Alas, fate finally intervened. I glanced away for a moment, and when I looked back, the berry was smashed on the sidewalk.

I recalled my sort-of life mantra — nothing, no matter how delicious and wonderful, lasts forever. Likewise, it may be, to our dismay, and my grandmother's dream genes, the way of Ljubljana, and Slovenia. Perhaps I'm wrong, and anyway we're still coming back, to savor ambiance of the "club," deep friendships, and drink from that well of wonderfulness, while we can. But I think I'll just stop telling folks what a swell place it is, lest they may actually all come, eroding our pleasantness.

If there’s a story you’d like to share about Slovenia, then please get in touch at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

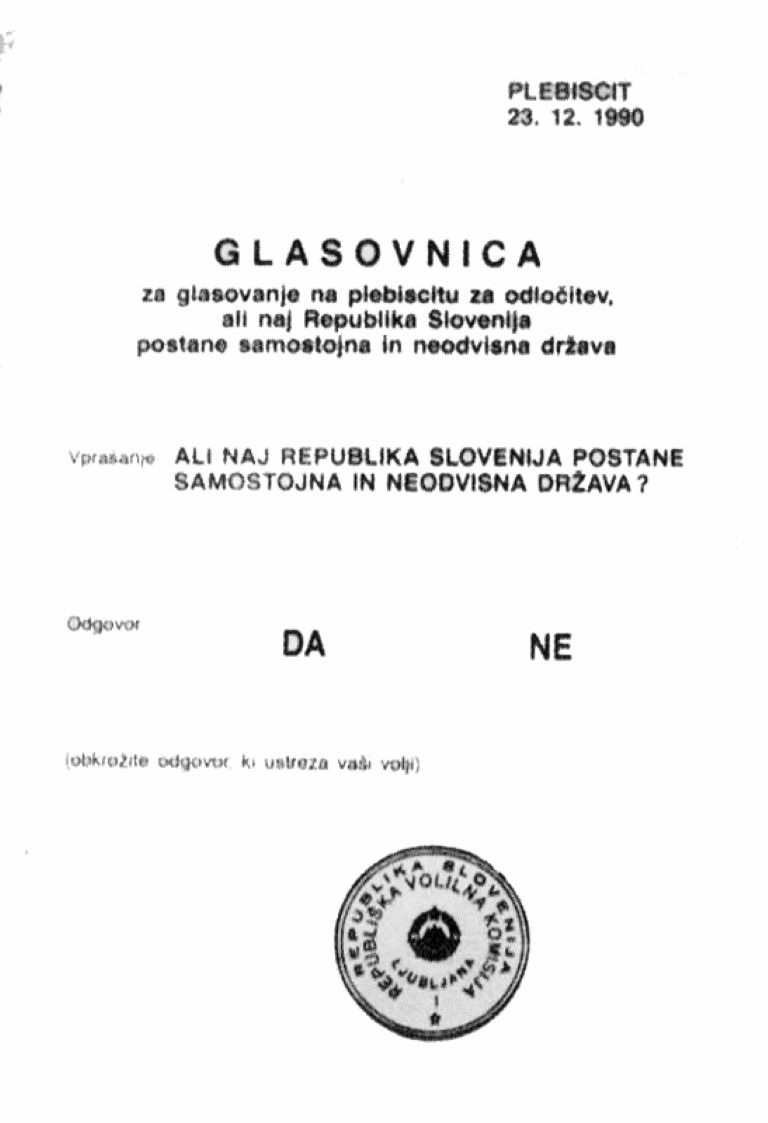

On December 23, 1990, Slovenia held a plebiscite on whether to move towards independence from Yugoslavia. The question asked was: "Should the Republic of Slovenia become an independent and sovereign state?" (Ali naj Republika Slovenija postane samostojna in neodvisna država?).

The paper used in the plebiscite. Wikimedia

As reported in the New York Times the following day, some politicians worried that a vote for independence would lead to trouble in the other, more ethnically mixed Yugoslav republics. As Mile Šetinc, vice president of the Liberal Democratic Party, is quoted in warning against a yes vote: "There are lot of Croats in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and there are lots of Serbs in Croatia, so every involvement with those groups risks real civil war."

The official results were announced on December 26, with 94.8% of those who voted supporting independence, thus beginning a six-month countdown to independence being formally declared. This eventually took place on June 26, 1991, precipitating what would come to be known as the Ten-day War (desetdnevna vojna), lasting from June 27 to July 7, which, while securing Slovenia’s independence, also started the beginning of the much longer, and bloodier, Yugoslav wars.

Until 2005 the national holiday was known as Independence Day (dan samostojnosti), but in September of that year it was changed to Independence and Unity Day (Dan samostojnosti in enotnosti).

December 20, 2018

In 1861 the painter Ivana Kobilica, one of the most famous Slovenian artists of all time, was born in Ljubljana.

Ivana Kobilica managed to achieve what her male colleagues only dreamt of: she had several exhibitions at the prestigious Paris Salon and became an associate member of the French National Association of Fine Arts. She lived and worked in many of the European capitals, including Vienna, Munich, Paris, Sarajevo, and Berlin, but returned to Ljubljana at the beginning of the WWI.

After the so-called Munich period during which brownish colours prevailed in her paintings, purple, blue and green took over during her Paris period, which were joined by white during her Berlin phase. Her opus is characterised by depictions of family members and children, portraits of bourgeoisie of Ljubljana and, above all, flowers.

Many of her most iconic paintings are part of the permanent exhibition of Slovenian National Gallery.

Ivana Kobilica was also the only woman depicted on a 5,000 Slovenian Tolar bill before Slovenia switched to the euro.

December 18, 2018

In 1970 actor the Stane Sever died in Ribnica on Pohorje.

Sever was a legend of the Slovenian theatre, television and cinema. He performed in many classics, including the first Slovenian talkie On Our Own Land (Na svoji zemlji), Good luck, Kekec! (Srečno, kekec!) and Vesna. In these movies Stane Sever played Drejc, a beggar and math teacher (Vesna's dad), respectively.

December 17, 2018

In 1931 the fourth tram line started operating between the train station and Vič in Ljubljana. Part of the route went through Šelenburgova street (today’s Slovenska), which had as a result moved Ljubljana’s main promenade to Aleksandrova street (today’s Cankarjeva), between the post office and Tivoli Park.

At the beginning of the 20th century Ljubljana’s promenade began on today's Čopova street then went past the post office on Slovenska, through Congress square (Kongresni trg) and back to the Town Square (Mestni trg). With the change of venue to Cankarjeva after the new tram line, it got an extension to Tivoli Park and even further for meetings and assignations that would prefer some privacy.

The promenade was a place to meet and debate, but also a place to show off. Hats, gloves and walking sticks were a mandatory part of a gentlemen’s outfit. It started after 4pm during the week and after 11am on Sundays, when it was especially ceremonial and classy, with a brass band playing and the best fashions of Ljubljana on display.

The promenade disappeared completely at the beginning of the 1960s, when the streets became jammed with traffic rather than walkers, and the citizens of Ljubljana begun spending their days off outside the city in the coastal towns of Piran and Portorož.

Get to Know the 17 Historical Towns of Slovenia

There are many ways to plan a trip around Slovenia and lenses through which to view it, and one way to explore the country is through its historic towns. But how to choose these in a land that’s got so many? One way is by turning to the work of the Association of Historical Towns (and Cities) of Slovenia (Združenje zgodovinskih mest Slovenije), a group that includes 17 mostly medieval towns sited around the country, each of which has its own story to tell, with the full list being Idrija, Jesenice, Kamnik, Koper, Kostanjevica na Krki, Kranj, Metlika, Novo mesto, Piran, Ptuj, Radovljica, Slovenske Konjice, Škofja Loka, Tržič, and Žužemberk.

STA, 25 October 2018 - Slovenians will observe Sovereignty Day on Thursday, remembering 25 October in 1991, when the last Yugoslav People's Army soldiers left Slovenian territory four months after the end of the Independence War.

Get ready for the celebrations, September 7-10.