Ljubljana related

STA, 3 June 2019 - The Society of Slovenian Deportees 1941-1945 (Društvo izgnancev Slovenije, 1941-1945) urged Slovenia ahead of 7 June, Slovenian Deportees Day, to claim at least a symbolic portion of what it says remains around EUR 50 billion owed by Germany in war damages. The society's Ivica Žnidaršič believes Slovenians know too little about the deportations that started in June 1991.

Žnidaršič told the STA that the German occupying forces had deported 63,000 Slovenians. Around 45,000 were taken to German deportation camps, 10,000 to Croatia, 7,500 to Serbia, and 2,000 to Hungary, while around 17,000 Slovenians escaped to avoid being deported. There are believed to have also been 2,000 children among the deportees.

"Slovenian deportees remain the group of Slovenians that have been hurt the most, since we lost all of our property and never received reparations. We only secured our status as victims of war violence in 1995," she said.

According to Žnidaršič, the victims have been receiving modest annuities since then - 0.84 euro for each month of violence for the deportees and 0.50 euros for the refugees.

"A 2001 law gave us a one-off reparation payment of 25,000 Slovenian tolars or 104 euros for each month or 12,000 tolars for the refugees. There was also 864 euros paid for deceased parents. However, we never received any damage payments for the material damage," she added.

The Society of Slovenian Deportees 1941-1945 is pointing out that there is no statute of limitations for war crimes, which is why Germany still owes Slovenia around EUR 50 billion.

It expects Slovenia will claim at least EUR 3 billion, which would allow the construction of a centre for victims of war violence and secure EUR 6,000 to the still living deportees. Of what were around 80,000 who were deported or who fled there are only around 9,500 still alive today.

It was on 7 June 1941 that the deportations started with a large transport operation in Slovenska Bistrica. The day is marked by a number of events each year. The central one this year will take place at the central camp for the deportations of Slovenians in WWII at Brestanica pri Krškem.

STA, 8 May 2019 - Commemorating the liberation of Ljubljana at the end of the Second World War, tens of thousands will take a walk along a marked gravel path surrounding the city on Saturday. A barbed wire used to trace the path during WWII, when Ljubljana was occupied first by Italian and then German forces.

The 63rd Walk along the Wire event will kick off already on Thursday, when kindergarten children will set out to conquer a part of the hike, followed by primary and secondary school children on Friday.

The commemoration's highlight will be Saturday's hike as well as the run of three-member teams, which is not about winning, promoting solidarity and participation. The time of a third member or the weakest link is thus recorded as the team's finishing time.

The running event is also an opportunity for a few laughs, with last year's teams running under witty slogans, such as Turbo Snails, Rolling Stones and (Un)Tamed Shrews.

Instead of stamps the event's organisers would like to gradually introduce a mobile application tracking the teams' progress.

The three-day event is expected to attract more than 30,000 participants, even more than last year, when almost 25,000 hikers and some 5,000 runners participated in the memorial walk.

The accompanying cultural programme will kick off on Saturday morning with a performance of the Partisan choir, honouring the WWII resistance movement. Ljubljana Mayor Zoran Janković will then address visitors, marking Ljubljana Municipality Day, followed by a concert of the Slovenian pop singer Lea Sirk.

The full programme, in Slovene and English, is here

Unlike at the Ljubljana marathon, there will not be many roadblocks, particularly not on Thursday and Friday, with some minor ones and city traffic detours in Ljubljana's centre on Saturday.

A barbed wire was put around Ljubljana in February 1942 by the Italian occupying forces to stop supplies to the Partisan resistance movement.

Ljubljana was the only European capital at the time to be locked out in such a way, with the regime lasting 1,170 days until the end of WWII in 1945 - Ljubljana was liberated on 9 May.

STA 26 April 2019 - On the eve of Resistance Day (27 April), a ceremony will be held in Kranj on Friday to remember the Liberation Front (Osvobodilna fronta - OF), an undercover organisation which spearheaded resistance against Nazi and Fascist occupation in World War II.

Addressing the national ceremony, parliamentary Speaker Dejan Židan said resistance should nowadays be perceived as the ability to survive, as self-confidence and responsibility. He also urged for the past not to divide us but to unite us for the future.

We seem to quarrel even more about the developments in WWII than those who fought during the war, he said, expressing disappointment at attempts to revise history. He also regretted that the unity of Slovenians from 28 years ago when Slovenia became independent had gradually faded away.

Židan sees independence, "which was achieved with a collective decision of the Slovenian nation for independence, with Territorial Defence's military courage, the determination of the police force, diplomatic achievements and the boldness of the media, as the latest historical test of Slovenian resistance".

For Slovenians, World War II started on 6 April 1941, when Germany attacked Yugoslavia; just three days later, Yugoslav soldiers, who put on only weak resistance, left Slovenia or were captured.

The territory of present-day Slovenia was divided between Germany, Italy and Hungary, with a small portion of land near Brežice in the east coming under the Independent State of Croatia, a Nazi puppet state.

With the exception of members of the German-speaking and Hungarian minorities, the majority of the Slovenian population could not reconcile themselves to the occupation.

As historians Zdenko Čepič and Damijan Guštin put it in their book Images of Lives of Slovenians in WWII, it was only a matter of time when and how they would resist.

The Anti-Imperialist Front, as it was initially known, was formed in Ljubljana on 26 April 1941, the day when Hitler visited Maribor, or two weeks after occupation and ten days after the Yugoslav authorities in Belgrade surrendered.

The movement was founded at the home of intellectual Josip Vidmar (1895-1992) by representatives of the Communist Party of Slovenia, the Sokoli gymnastic society, the Christian Socialists and a group of intellectuals.

It featured no political party from the pre-war period, but fractions of these parties from across the political spectrum as well as political dissidents, resulting in a mixture of worldviews.

Nevertheless, the leading role was all along played by Communists, even if there were only some 1,000 members. Having spent 20 years working undercover as an illegal organisation was what made them best suited to work in an occupied territory.

Yet there was infighting for Liberation Front leadership as early as 1942, including a clash between the Communists and Christian Socialists, which resulted in the Dolomite Declaration.

In the March 1943 declaration, the founding groups agreed to the domination of the Communist Party, a watershed moment which signalled the end of political pluralism.

The Liberation Front spread its network around the country regardless of the borders set up by the occupying forces. According to Čepič and Guštin, it was a kind of a state within the state, at least in Ljubljana in the first year.

To protect the Liberation Front and its leadership, the Security and Intelligence Service (VOS) was established upon the Communist Party's initiative.

Apart from VOS, the National Protection service was organised as a military organisation with small units operating around the country and at factories.

The Slovenian Communists were tasked to organise an armed resistance by the Yugoslav Communist Party's politburo and started organising it past the Liberation Front.

Thus, they set up military committees to lead the armed resistance on 1 June 1941 and the command of Slovenian partisan corps on the day of Germany's attack on the Soviet Union.

Čepič and Guštin say that left radicalism and sectarianism on the part of some Communists caused frictions within the Liberation Front, which its leadership and the Communist Party fought strongly against.

There were also problems in executing "the people's power" as individual partisan commanders terrorised the population, resorted to torture and even executions.

And even if the Communists had clearly stated their goal of pursuing political change after the war, people were willing to support the Front and cooperate with it.

Čepič and Guštin cite a statement by the leader of the Slovenian People's Party's illegal military organisation during WWII, Rudolf Smersu, who said "people simply flocked to them!"

This was despite warnings by Slovenian politicians that the Liberation Front was but an extension of the Communists.

And views on the Liberation Front and on Resistance Day, which used to be termed Liberation Front Day until renamed in the early 1990s, still differ.

But historians say that instead of engaging in basic studies there is too much focus on the role of the Liberation Front, which leads to rather general and biased views.

On Saturday, a series of local events will be organised around Slovenia, including memorial walks, and the Presidential Palace will open its door to visitors.

All our stories on World War 2 can be found here

We recently ran an interview with Robert Posl, the translator of a book, Through the Eyes of Partisan Soldier, which tells the story of a Slovenian Partisan in the Second World War.

We also posted a video of an interview with a central figure in a key episode in that book, Ralph Churches, the Crow in “The Flight of the Crow” (also known as the Raid at Ožbalt).

Today we continue this series with an episode of WWII’s Great Escapes that recounts the same tale. It was filmed on location, in Slovenia, and includes interviews with prisoners who escaped, Partisans who helped them, and others with links to the story.

All our stories on World War 2 can be found here

STA, 24 April 2019 - President Borut Pahor addressed a ceremony commemorating the Jews deported during World War II from Lendava at the synagogue in this eastern-most Slovenian town on Wednesday. He underlined that the great European idea of peace and security must be protected, the president's office said in a press release.

Ob 75. obletnici deportacije lendavskih Judov je predsednik republike pred pričetkom komemorativne pietetne slovesnosti položil venec k spomeniku žrtvam nacifašističnega nasilja na judovskem pokopališču v Dolgi vasi. pic.twitter.com/IC5tRosx0u

— Borut Pahor (@BorutPahor) April 24, 2019

The ceremony marked 75 years since a vast majority of Slovenia's biggest Jewish community was deported, a blow from which it never recovered.

Pahor dedicated his address to Erika Fürst, a holocaust survivor, inviting her to join him next year at the ceremony marking the 75th anniversary of liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

Atrocities start when small signs of exclusion become the norm. Therefore, it is key to recognise the importance of early detection of exclusion, intolerance and hatred, said Pahor.

Before the ceremony, the president laid a wreath at the Dolga Vas cemetery, the biggest Jewish cemetery in Slovenia, alongside Lendava Mayor Janez Magyar and city councillor Ivan Koncut, who laid a wreath on behalf of the state of Israel.

All our stories on Jewish Slovenia are here

April 1941 saw the invasion of Slovenia by Germany, Italy and Hungary, as noted here. April 26 then saw the visit of Hitler to Maribor, or Marburg an der Drau , as he knew it. That story was told in more detail in an earlier article, and in this one we’ll simply be presenting of the striking images and film footage we came across while doing some related research, showing Nazis in Slovenia.

German soliders crossing from Austria into Slovenia, entering Maribor

Hitler in Maribor

Hitler, and other Nazis, meeting an ethnic German (Volksdeutsche) in Maribor

Volksdeutsche in Maribor

Himmler in Maribor

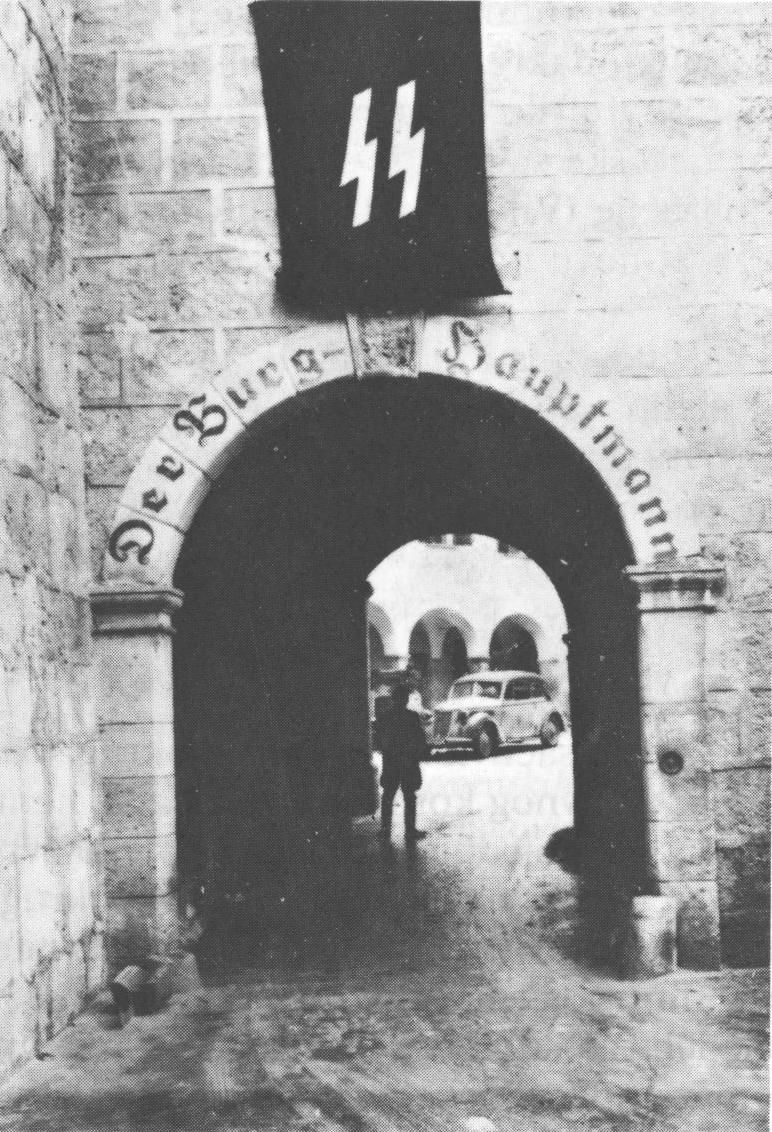

Nazi headquarters in Maribor

German soldiers on Maribor ulica

The entrance to Castle Brestanica (Grad Rajhenburg)

Volksdeutsche in Celje

Celje

Celje

Nazi officials in Bled

Finally, here's a train ride from 1941, with much of it in Slovenia

STA, 13 April 2019 - President Borut Pahor and US congressman Paul A. Gosar honoured eight crew members of a downed US bomber, who lost their lives in a crash near Polzela (NE) during WWII, as keynote speakers at a ceremony on Saturday. The event also celebrated Slovenian-American Friendship and Alliance Day.

Pahor marked the 75th anniversary of the bomber's downing by laying a wreath at the memorial commemorating the crew members.

In his address, Pahor highlighted the long tradition of friendship between Slovenia and the US, adding that it also allowed for occasional differences in positions.

Tradicionalna slovesnost "Dan slovensko-ameriškega prijateljstva in zavezništva" v Andražu nad Polzelo. PRS je ob 75. obletnici strmoglavljenja ameriškega bombnika B-17 položil venec k spominski plošči v spomin osmim članom posadke, ki so ob tem izgubili življenje. pic.twitter.com/e0ftJQFMZT

— Borut Pahor (@BorutPahor) April 13, 2019

While the present US administration may perhaps not share the views of Slovenia and the EU, Pahor said that there was always a search for what unites us, as this was important both for Slovenia and the US.

Gosar, a Republican of Slovenian descent who is visiting Slovenia for an extended weekend at the invitation of the president, thanked Pahor on the warm reception he has received in Slovenia.

He argued that Slovenian generosity and courage had also been what had given hope and light to the downed US soldiers.

Gosar received the Golden Order of Merit, one of Slovenia's highest state decorations, on Friday, for his contribution and cooperation in strengthening relations between Slovenia and the US.

Gosar will also hold meetings with Slovenian officials to further strengthen the relationship between the two countries on Monday.

The congressman recently established the House of Representatives Friends of Slovenia Caucus, which he is to co-chair.

The US bomber B-17 flew from an Italian military base along with other 233 combat aircraft and was headed toward the Austrian Carinthia to bomb the Steyer factory, which was contributing to the German military industry at the time. It was shot down at the Andraž settlement near Polzela on 19 March in 1944.

Eight crew members died in the crash, while two of them were taken as prisoners of war and survived in POW camps. The crew members belonged to the 15th US Air Force division.

The occupation of Ljubljana by Italian Fascists lasted from April 1941 until September 1943, and was a time of horror, with around 25,000 people from the area deported and sent to concentration camps, as well as the city itself being surrounded by barbed wire. Moreover, when the Italians left the Germans moved in.

However, this story won’t dwell on these details, but instead presents some Italian archive footage showing scenes of the occupation, with many sights and buildings that will be familiar to those who only know the city today, in happier times.

All our stories about Slovenian history are here

Last week we posted an interview with Ralph Churches, a former Australian soldier who spent time as a prisoner of war in Slovenia, before escaping in a daring adventure known as the Raid at Ožbalt, or “the Flight of the Crow”. We first become aware of his story because of a new book published in English, a first person account of life as a Partisan solider in the Second World War, written by someone who was part of the same adventure. Curious to learn more, we got in touch with the translator, Robert Posl, and asked how he came to work on this project, and what he learned.

First of all, what’s your connection with Slovenia?

My parents originated from the former Yugoslavia. My father from near Rogatec, my mother from Croatia, near Zadar. She moved to Slovenia, where she met my father. In 1970 they moved to Germany. My father simply did not see a future staying in Yugoslavia.

I was the third child, born in August 1974. In spring of 1975, we moved to South Africa. The apartheid regime of South Africa was in full swing and was encouraging and inviting people to move to South Africa. So that's what my parents did, along with their three toddlers. I obviously don't remember any of that, since I was barely six months old.

We lived quite a decent and progressive life in South Africa. We as children had no contact with Yugoslavia. And even though my parents had brothers and sisters in Yugoslavia (Slovenia and Croatia), they too had almost no contact. The Communist way there was distinct and powerful until the 90's, when everything started to change. The war in Slovenia was short, only four days, with barely any conflict or anything.

Slovenia was then 'free' and with a promising future, quickly stepping forward to becoming a European nation. We started hearing about relatives we had never heard about before. Then in December 1991 my uncle and his wife came to visit us in South Africa. While things were looking quite promising for Slovenia, the opposite was for South Africa, as the apartheid era was coming to an end. So the obvious happened, the decision to move to Slovenia quickly grew.

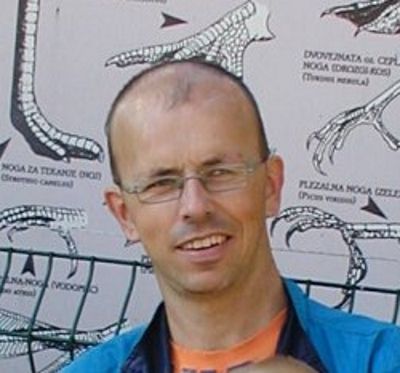

Robert Posl

And so you moved back?

Yes, and after moving from South Africa to Slovenia, to Europe, I felt that I was now properly introduced to history. Moving from a country which has bareky any history compared to that of mainland Europe. Most of the countries in Europe have also put significant efforts into maintaining and restoring their cultural heritage, so now I could see and even touch it, compared to only reading about it. Slovenia is thus dotted with numerous buildings and monuments, which clearly express its history. Especially the countless number of memorials and plaques reminding us of the Second World War.

One thing I heard about a lot about the Partisans. The most common thing I’d hear was how difficult it was and how they lived in poverty and in hunger, with ragged clothes and inadequate equipment. My reaction was obvious, “who would want anything like that? So unpleasant!”

So that’s how you came to translate this story?

Yes and no, because there’s more of a family connection than just an interest in history. Some years ago my wife’s uncle, Alojz Voler, published his autobiography and experiences during the war, when he served with the Partisans. Alojz kept the publication quite quiet, mainly only sharing it with relatives and acquaintances. I paged through it a couple of times, reading some sections and admiring the photos.

Then in the spring of 2017, a car with foreign registration plates stopped in front of his house. They were from England, except for the translator who was with them. They were looking for a man who was involved in a remarkable event during The Second World War, “The Flight of the Crow”. A team were in Slovenia making a movie about this great event, something most people didn’t even know happened.

When I learnt more and that Alojz was involved in it, I right away suggested that his autobiography be translated into English and to include the details of this event. The more I thought about it, the more I saw the need for this to be done.

Alojz Voler, with German recruits. He served in the German army for 14 months before he managed to desert them and return to Slovenia, where he then joined the partisans.

What was that like?

I got to know more of the details and specifics about Alojz and the life he lived. He was born in 1925 on a farm in the Savinja Valley in Northern Slovenia. Not only was I getting to know him, but I was also getting to know what it was like living in that period. The onset of the Second World War and the influence of the aggressors, which was long felt before the conflict even started.

The Second World War was for Yugoslavia more than just the invasion and engagements with German forces. A significant part of it was the tension and politics within the country itself. Already in primary school, Alojz would be tolfd negatuve things about the Partisans, and how they lived in hunger and poverty. Surprisingly, it was allo very to what I so often heard when I moved to Slovenia.

For Alojz to follow his heart was a journey in its self, and to join the Partisans was an almost unimaginable and treacherous step to make. I admire how Alojz expresses this idea: To go into resistance with almost bare hands, against the most elite forces of the world at that time, was an almost fantasy. But it was no fantasy, it was the cruel reality.

Starting with this translation at first only fed fuel to the fire of my curiosity. What kind of person, and why, would want to be part of the Partisans? But by following Alojz’s life throughout his book, my questions were answered.

Alojz on the right, with other members of the KNOJ (Korpus narodne obrambe Jugoslavije). Photo taken after the war ended.

The book obviously has many other stories, but how was Aljoz involved in the “Escape of the Crow”?

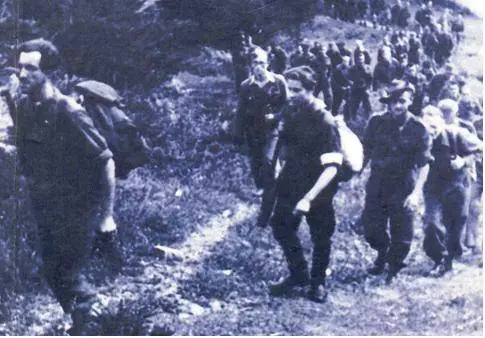

The battalion Alojz was in was based to the west of Maribor, nearby the Ožbalt work camp. Some of the Partisans were chosen to escort a group of six POWs, including Ralph Churches, away from the area ASAP. The next day they returned and managed to free the rest of the captives, and it was then that Alojz met and helped them to safety and away from Ožbalt before the Germans intensified their search for the prisoners.

Here is a photo, which is also on the cover of A Hundred Miles as the Crow Flies. The guy on the left, almost out of the picture is Franjo Gruden, the leader of the escort team. Alojz was at the back to make sure nobody fell behind.

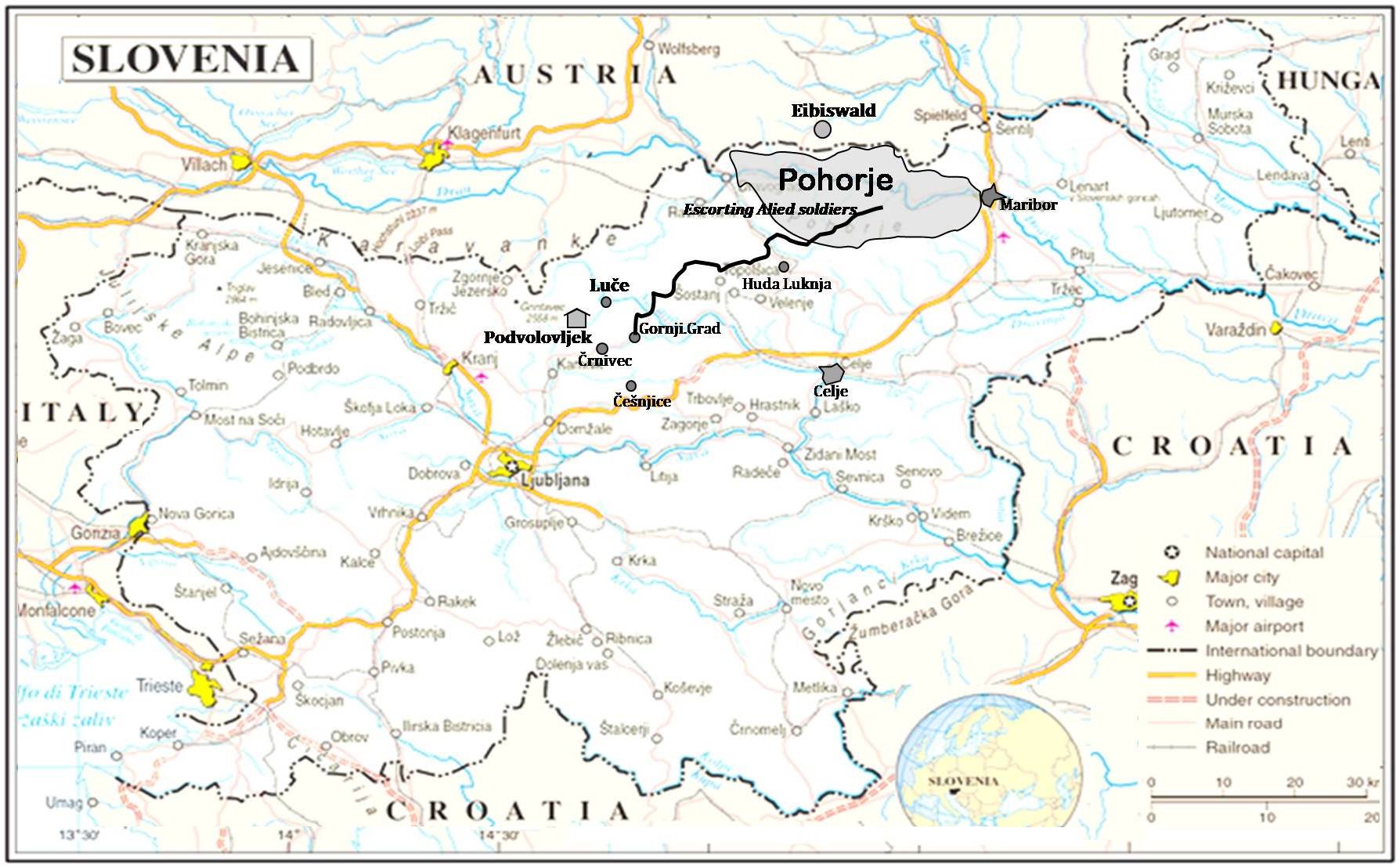

And here is a map I made for the book. You can see where they went, up to Gornji Grad, then another group of partisan soldiers took over to escort them further.

And what you have learned from the book?

For me the most important things about working on this project are being able to share a part of history, but more than that, it’s about giving Alojz that feeling of pride. At 94 years old it’s quite something that his story is finally being told, and that he’s the one to tell it. And so I hope that more people will hear about him and what he did during the war.

While doing the translation, and still after, people would ask me: “Who is paying for this? How much are you being paid?” My answer – Alojz has paid me; with the truths and experiences from his heart, as seen by an ordinary, humble man. And with the knowledge, that I can now confidently say, “I know who and what the partisans really were”.

Alojz Voler, Niel Churches & Monty Halls, Spring 2017

If you’d like to read Alojz’s story, Through the Eyes of a Partisan Soldier, then you can pick up a copy, in both paper and digital forms, from Amazon, while all our stories on World War Two are here

Through the Eyes of a Partisan Soldier is a recently published first-person account of one of the many notable events that occurred in Slovenia during the Second World War, one that’s known in English as the Raid at Ožbalt, or “the Flight of the Crow”. We’ll shortly be running an interview with the man who translated the book, which was written by his wife’s uncle, Alojz Voler, but in this post we’ll set the scene.

In short, in the summer of 1944 105 Allied prisoners of war were rescued by Slovenian Partisans, the story recounted in the book. Since many were being held at a camp by the village of Ožbalt, just west of Maribor, this daring rescue turns up on Wikipedia as the Raid at Ožbalt. The POWs and Partisans made their way south to Semič, near today’s border with Croatia, where they met up with an Allied aircraft that had flown in from a liberated part of Italy, which they then escaped to true freedom on.

The location of Ožbalt

The raid on Ožbalt was facilitated by Private Ralph Frederick Churches, a POW who, having made two previous attempts to escape, knew that the locals were hostile to the Germans and willing to help. Churches then made a third, and finally successful escape with six others prisoners, and managed to persuade a group of around 100 Partisans to help others do the same, with a total of 105 POWs escaping from the work camp.

But why is the story also known as “the Flight of the Crow”? Because Private Churches was from South Australia, with South Australians having the nickname “crow eaters”. A remarkable man, with a remarkable story, you can here more in his own words below.