April 1, 2019

In 2007 Slovenia celebrated the 50th anniversary of the death of Slovenia’s greatest architect, Jože Plečnik. In the same year an inter-ministerial commission was established to carry out the strategy of the protection of cultural and natural heritage, following the 1972 UNESCO recommendation and other legal international commitments for preservation of civilizational achievements.

One of the stages of this process was to prepare a preliminary list of potential world heritage candidates, and in this process all of Plečnik’s work in Ljubljana was declared cultural heritage of national importance in 2009, hence becoming a possible candidate for UNESCO civilisational heritage protection list. In his lifetime Plečnik’s architecture marked several of Central European cities significantly, in particular Ljubljana and Prague. Since the international positioning on the works of the 20th century is pretty much unclear at the moment, so is the process of recognising Plečnik's work, which was submitted for evaluation in 2015, including one work in Prague and a colleciton of works in Ljubljana.

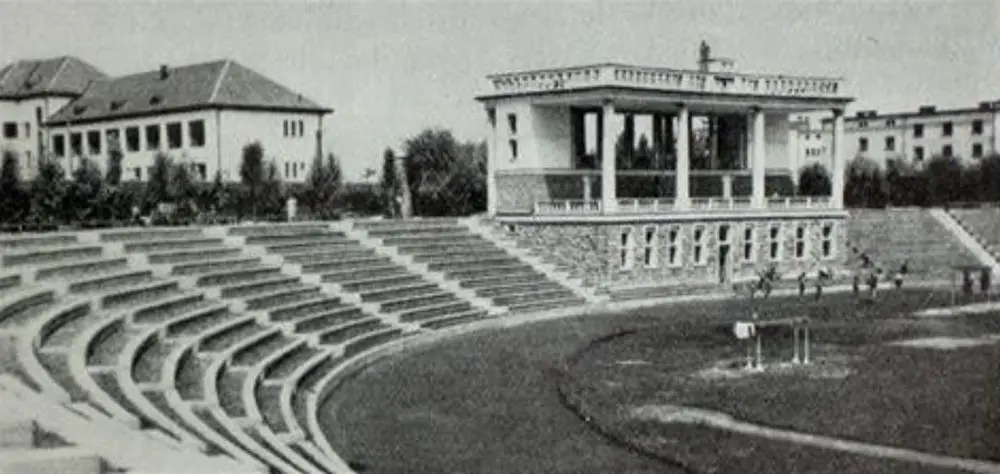

Regardless of the civilisational prospects of Plečnik’s nomination for UNESCO status, his entire Ljubljana work was declared cultural heritage and of national importance in 2009, and part of that heritage is Central Bežigrad Stadium, the construction of which spanned over the second half of the 1920s and into the 1930s.

Moreover, in 2007 Ljubljana and Slovenia in general were suffering from the lack of a stadium that could host a major sports event and provide roofed tribunes for an adequate number of spectators. Providing the capital with such a venue was one of the 2006 local election campaign promises of Zoran Jankovič, Ljubljana Mayor since 2006.

In 2007 the city government of Ljubljana (MOL) found an interested investor for the reconstruction of Plečnik’s Stadium, a slot machine baron Joc Plečečnik, who also owned a gambling salon in Grosuplje and the Hotel Lev’s Casino until 2018, when they were sold to Austrian gambling giant Novomatic. According to Peter Rondaij’s open editorial for Dnevnik, Pečečnik’s interest in renovating the stadium was strongly related to his attempts at a Nevada (USA) non-restricted gambling licence, which would have been (and eventually was) granted to him on the condition of his general good track record that also involved a proof of active engagement in the field of culture.

The winner of the public competition for the reconstruction of Plečnik’s Stadium 2009, designed by the German architectural studio GMP, was based on detailed urbanistic plans drawn-up by city Vice-Mayor Janez Koželj half a year later. The inspiration for the spatial planning seems to be heavily influenced by Pečečnik’s original plans for a skyscraper and a vast commercial area spreading deep underground. In the original plans five, not three, commercial buildings were intended by the northern wall of the stadium, currently hosting public gardens that have been in public use since the neighbourhood was built in the 1930s.

In October 2007, Bežigrad Sports Park Ltd. was established with the main shareholder being Pečečnik’s GSA (59%), the City Government of Ljubljana (28%) and Slovenian Olympic Committee (13%), the latter two contributing their shares in land. The property was immediately closed to the public using a construction fence and the project seemed to have proceeded without much need for either transparency or participation on the side of the public. Starting immediately after the fencing of the premises, citizens living nearby could only observe how the first thing to happen behind closed walls in December 2007 was the removal of floodlights and grass surface altogether, along with the drainage system. Part of a southern wall was demolished so that heavy trucks could get in and out. At the beginning of 2008, local residents also reported that all copper gutters and drain pipes has been removed from the gloriette, which was also reportedly deprived of its electric installations and then left with windows and doors open, which was done, according to speculation of the locals, to let vandals in so that they could destroy what the weather and time would not. According to Rondaij, this approach isn’t new. With “self-demolition” of protected buildings investors can clear a prime location for any development they want.

Meanwhile, in March 2008 an agreement was signed for another sports centre in a much more appropriate location for hosting masses of sports fans and concert goers. Right next to the highway ring-road of Ljubljana, a stadium and another roofed hall has already been completed and pretty much functional since 2010 in Stožice. With these facilities in place, the urgent need for a sports centre ceased to exist and the arguments for another such complex in the downtown area of a “green” capital that aims to replace dirty traffic with bicycle lanes and trees doesn’t seem to hold much water. Especially since this concrete moneymaking monster with several football field sized floors of parking lots is supposed to grow above and under a monument of protected cultural heritage.

The whole process seems to have taken a few shortcuts, one of them being the circumvention of the affected public, in particular the Fond community dwellers, who were left out of all discussions. In 2009 new spatial plans were shown to them which is how they learned that they would lose their gardens and views. The city government gave up the land as its 29% investment in Bežigrad Sports Centre Ltd. It was only from these plans, drawn up without alerting the general public, that one resident even found out that her house was set for demolition (source).

How a polarising project like this can continue to survive into the present is a mindboggling question. One of the explanations worth mentioning has been explored in detail in a graduation thesis, written by Danaja Visković Rojs. In short, the thesis contextualises the problem into the weak political culture of transitional societies, in which representatives lack the understanding of the nature of legitimacy of their governing jobs. Public participation in important decision-making processes, such as spatial planning, is a fundamental ingredient of democratic societies, something leaders of countries in transition to democracy find difficult to understand, instead taking their role of decision-makers as absolute. In return they lose the legitimacy of their political leadership, which they tend to compensate for with proofs of legality, exacerbating the conflict further.

In 2010 Zoran Jankovič, the Mayor of Ljubljana explained to Delo why the project continues to persis: while the city government contributed only land and wouldn’t lose anything by the contract ending, Joc Pečečnik invested money and would therefore lose €15 million if the project didn’t get through, which wouldn’t be fair to him. Which method of accounting brought Pečečnik to this number, Mayor Jankovič did not explain. The list of maintenance costs according to the official project’s website amounts to only €77,500. Yet the Mayor of Ljubljana seems to have a greater understanding for the interests of the city’s business partner, by now a “small king” of Las Vegas, rather than for the citizens who elected him.

Not surprisingly, in his interview for Delo Joc Pečečnik expressed great satisfaction with the city government’s collaboration, saying he has “no complaints” whatsoever. His take on Fond’s community protests, that are delaying the construction of the stadium, is simplistically legalistic with a neo-liberal newspeak definition of “public interest”: nobody has the right to interfere with his private property and it is the state’s duty to “protect the entrepreneur” and “allow him to create jobs and added value”. If someone out there wishes to use the stadium for “their own personal interest and (use it to) grow lettuce”, he has already offered to “buy his share for a very reasonable price”.

The city government and the Ministry of Culture told 24UR that they do not have the money to buy Pečečnik’s share. But do they even need to? They can simply leave the project and allow the lettuce continue to grow.