Ljubljana related

STA, 25 February 2022 - President Borut Pahor offered a formal apology on Friday to the 25,671 people who were erased from Slovenia's register of permanent residents 30 years ago. He said this had been an unconstitutional act, a violation of human rights and apologised for all the "wrongs and suffering" it had caused.

"Please accept my sincere apologies on my behalf and on behalf of the state for the unconstitutional act of erasing you from the register of permanent residents, for the violation of your human rights and for all the injustice and suffering that this act caused you and your families," Pahor said at today's ceremony at the Presidential Palace.

The president also expressed deep regret at "the losses you suffered as a result of the erasure, in your relationships with your loved ones, in your property and in the opportunities that could have turned your life around for the better".

"Today we are also taking moral responsibility for the unconstitutional act of erasure, and we are committing it to our collective historical memory," he said.

"I regret that you had to wait far too long for action to be taken to redress the wrongs done to you, even after decisions were adopted by the courts. I am aware that the measures only went so far to address the issues and that many of you are still suffering the consequences of the erasure.

Obeležitev 30. obletnice izbrisa oseb iz Registra stalnega prebivalstva RS #STAvživo @vzivo_si https://t.co/lglDnKkgC5

— STA novice (@STA_novice) February 25, 2022

"I realise that an apology will not make up for what you lost by being erased. By no means," the president said.

"However, today, we are putting an end once and for all to an era of denial and a failure to acknowledge all the suffering and all the grave, tragic consequences of the erasure that are still ongoing."

The president clearly stated that the erasure of 25,671 people, including 5,360 children, from Slovenia's register of permanent residents had been an "arbitrary and unjust act, it was illegal, unconstitutional and discriminatory, and it constituted a violation of human rights".

According to Pahor, the erasure denied people the legal basis for the right to work, the right to healthcare and social protection, the right to higher education and the right to buy a home.

Many were expelled from the country, and many families were separated. Many fell ill, and some even died prematurely without access to healthcare services, he noted.

"Because the erasure was carried out quietly, without informing those affected, in the first years following the erasure they could not understand why they were suddenly, without explanation, no longer able to support their families, go to their parents' funeral, or return to Slovenia, to their homes, after visiting relatives."

Pahor said he wished he could conclude his apology with an assurance that this would never happen again. "The erasure, as well as other events in our vicinity, show us that the rule of law and human rights cannot be taken for granted, that they must be constantly watched over and constantly fought for."

He urged all national and local authorities, as well as civil society institutions that are able to do so within the scope of their tasks and powers, to keep the memory of the erasure and the erased alive, to protect the rule of law and human rights as "our constant and shared concern is that such a thing should never happen again".

He also called on all future governments and all relevant institutions to protect and enable the independence of the judiciary, independent institutions, guardians of democracy, to respect the independence of the media, and to provide space and mechanisms for civil society to function.

Irfan Beširović, head of the Civil Initiative of Erased Activists, said today was a new day for the erased. But he warned that all injustices had not been eliminated yet and that the erased still lived without a proper status in Slovenia.

"Finally, after 30 years of agony, humiliation, we have received an apology from the state," he said, thanking the president.

He believes the apology means a recognition of the erasure and its consequences. "It is not a victory, but for me personally it is a moral victory that we have witnessed it."

STA, 7 July 2021 - Thirty years to the day, the Brijuni [sometimes written Brioni] Declaration was adopted, ending hostilities between Yugoslav and Slovenian forces in the ten-day independence war and suspending Slovenia's independence activities for three months. It was the first international agreement between Slovenia and the EU's predecessor, the European Economic Community (EEC).

Following diplomatic efforts that began after the outbreak of independence war in Slovenia, the declaration was signed on the Brijuni Islands in Croatia on 7 July 1991 after 15 hours of negotiations. The agreement was endorsed by the Slovenian Assembly on 10 July.

The parties to the declaration were the representatives of Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, the Yugoslav federal authorities and the trio representing the EEC, made up of the foreign ministers of Luxembourg, Portugal and the Netherlands.

The representatives from Slovenia were the president of the Slovenian presidency Milan Kučan, Prime Minister Lojze Peterle, Foreign Minister Dimitrij Rupel, the Slovenian representative in the Yugoslav Presidency Janez Drnovšek, and the Speaker of the Slovenian Assembly, France Bučar.

The Yugoslav delegation featured Prime Minister Ante Marković, Interior Minister Petar Gračanin, Foreign Minister Budimir Lončar, Deputy Defence Minister Stane Brovet and other members of the Presidency of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY). Croatia was represented by President Franjo Tuđman.

In the declaration, the parties agreed that in order to resolve the situation peacefully, several principles must be strictly respected, including that only the peoples of Yugoslavia can decide their own future, and that negotiations should start immediately, and no later than 1 August 1991.

The European Community pledged to offer assistance in finding peaceful and lasting solutions, provided that all obligations are strictly respected.

In an annex to the declaration, it was agreed that Slovenian police would control Slovenian border crossings in accordance with Yugoslav federal regulations.

The parties agreed on the unblocking of all units and facilities of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), the unconditional withdrawal of JNA troops to barracks, the removal of all road barricades, the return of all JNA assets and equipment, and the deactivation of all Slovenian Territorial Defence units.

The Brijuni Declaration did not fully satisfy any of the parties involved in the Yugoslav crisis. For Slovenia, the most contentious provision was the three-month suspension of independence activities, which was seen by some as a temporary renunciation of independence, the unblocking of JNA barracks, and the return of JNA assets and equipment.

The declaration was met with mixed reactions in the country - some considered it necessary to stop the war at all cost, while others felt that the Slovenian delegation at Brijuni gave up what had been gained with the Declaration of Independence and during the ten-day war.

But even though Slovenia committed to a three-month suspension of the independence process, the process was actually accelerated.

The Yugoslav leadership realised that it would not be able to stop Slovenian independence and decided to withdraw its troops from Slovenia within three months on 18 July 1991. The last JNA troops left the port of Koper on 25 October.

Later that summer, on 27 August 1991, the EEC set up an arbitration commission to resolve legal issues related to the break-up of Yugoslavia. The commission's conclusions paved the way for the international recognition of Slovenia.

As historian Božo Repe pointed out for the STA in April, the Brijuni Declaration was the first international document that recognised Slovenia as an international subject. With it, Slovenia passed the maturity test in entering international relations and saved itself from war, he said.

Prime Minister Janez Janša also spoke about the declaration and the negotiations in Brijuni when he presented the priorities of the Slovenian EU presidency to the European Parliament on Tuesday.

He said that the Brijuni negotiations had restored Slovenia's hope in Europe, which had been striving to preserve Yugoslavia until the start of the war in Slovenia.

STA, 22 February 2021 - A predominantly Slovenian group of landowners in San Dorligo della Valle/Dolina municipality in Italy has reclaimed ownership of large tracts of lands under a landmark judgement recently handed down by an Italian court, a development seen as creating significant economic opportunities.

Based on new documents dated to the early 20th century, the Dolina "srenja", a kind of self-governing community of landowners, managed to reverse a 1931 court verdict under which the land had been made public property, the Trieste-based Primorski Dnevnik reports.

The srenja managed to prove that they were the rightful owners of the land, and not the municipality. The judgement affects 88 plots of land stretching over 233 hectares, some of it in the picturesque Glinščica Valley.

Over the years some of the land has been repurposed for infrastructure such as roads, which is why the srenja and the municipal authorities will now determine which of the plots will be assigned to the municipality and which will be left over for the landowners.

The two largest organisations representing the Slovenian minority in Italy, the Slovenian Cultural and Economic Union (SKGZ) and the Council of Slovenian Organisations (SSO) welcomed the decision in a joint statement.

They said it "opens a new chapter and has potentially positive effects" as the land may now be used for farming, forestry and tourism.

"But more than that, it returns the land to the original owners [...] who will now be able to manage it to the benefit of the home community."

STA, 22 December 2020 - On Wednesday, 23 December, Slovenia will mark three decades since a decision that is seen as a landmark in the nation's history: an independence referendum at which the overwhelming majority opted to leave Yugoslavia. The referendum results were declared three days later, on what is now celebrated as Independence and Unity Day.

Following a rising wave of pro-democratic movements in the 1980s, the first free multi-party general elections were held in April 1990. The Democratic Opposition of Slovenia (DEMOS) won, formed a government and completed key steps towards the independence referendum in cooperation with the opposition.

Lojze Peterle, the first prime minister, says the idea for a referendum had been around at the time DEMOS was formed, with the final decision to hold a vote taken at a 9-10 November meeting in Poljče, at which members of a commission that drafted Slovenia's constitution helped convince DEMOS deputies to confirm the proposed vote.

While the opposition wanted to shift the referendum to the spring of 1991, it eventually accepted the December date. In return, DEMOS and the government acquiesced to the rule that the referendum would be successful if at least half of all the eligible voters opted for independence. DEMOS had initially wanted an ordinary majority.

On 6 December 1990, the representatives of political parties and deputy groups in parliament signed a compromise agreement in which all signatories pledged to work together in preparing and executing the referendum. They stated that they were aware of the historical significance of the decision.

Based on that agreement, the parliament passed a law on the independence referendum. The vote was unanimous, with four MPs abstaining.

"The signing of the agreement was very important since it was a strong message to the people that Slovenian politics is united," Peterle has told the STA. Milan Kučan, president at the time, said the agreement had helped overcome distrust.

On 23 December, independence was confirmed with a 95% majority on a turnout of 93.2%, which means that over 88% of all eligible voters voted in favour. When the results were proclaimed shortly after 10pm, DEMOS leader Jože Pučnik famously said that Yugoslavia no longer existed. Both Peterle and Kučan say they never doubted the outcome of the referendum.

The results of the referendum were officially proclaimed on 26 December, which has since been celebrated as Independence and Unity Day. Immediately thereafter, proceedings for a formal declaration of independence were initiated and Slovenia declared independence on 25 June 1991.

Due to the coronavirus epidemic, celebrations of the landmark event will be muted.

President Borut Pahor will host an open day and address the people via video. The ceremony itself will be a pre-recorded TV show with an address by Prime Minister Janez Janša, while the National Assembly will hold a brief ceremonial session.

STA, 6 December 2020 - Three decades after Slovenia's parties reached a joint agreement on an independence referendum in which an overwhelming majority opted for independence, the country's first president Milan Kučan says unity cannot be taken be taken for granted, explaining why it is elusive now.

"Independence was a clear, understandable project. If there's no such project, appeals for unity are but a political cliche and an excuse for political impotence," Kučan told the STA in an interview.

What made unity over independence and its success possible were in his view four elements, which he believes could also be useful to politicians today.

"The most important one is that it could have never been a project of one part the citizenry against the other. If it were, the project, the plebiscite including, would never have succeed," he says.

"Nor was independence a romantic realisation of the nation's millennium dream, but the result of a series of thorough rethinks and decisions in the given historical circumstances, culminating in the political and economic crisis in Yugoslavia and the spread of nationalism."

Another key aspect was the legitimacy and lawfulness of independence through the passage of constitutional laws and the plebiscite law, and the "painful" debate on what quorum should be sought in the plebiscite helped overcome distrust.

At the time, the opposition parties, largely represented by groups that evolved from the former Communist party and other associations that existed under the former regime, believed a majority of all eligible voters should vote in favour in order for the referendum to succeed. This solution was adopted.

The fourth major aspect, according to Kučan, is that independence was a project of a country rather than a party.

"This is not to say that I underestimate the fact that the project matured within the DEMOS coalition, based on the concept of the Slovenian national programme that was more or less set down in volume 57 of Nova Revija," he said in a reference to the January 1987 issue of the literary journal.

Kučan never doubted the referendum on 23 December 1990 would succeed (on a turnout of 93%, 95% voted in favour of independence). "People were willing to accept the independence concept as long as politicians told them plain truth."

However, unity began to unravel soon after the country declared independence on 25 June 1991, which Kučan believes is because the awareness of the need for shared responsibility for the country was lost and the interests of a party, group and bloc have prevailed.

"The moment citizens realise we are being treated like fools, when the epidemic is being used as a cover for the pursuit of ideological and political interests and resorting to repressive apparatuses, trust in politics is gone. (...)"

"What has the government's dealing with the statistics office, media, museums and police got to do with the epidemic," he wondered.

Considering the suspension of financing of the STA "it may appear as if the government was running out of time and was in a hurry to subjugate all subsystems and institutions, while in fact it is how the largest ruling party has always operated and how it has understood democracy".

He finds it less understanding that the Democratic Party (SDS) is being uncritically supported by other coalition parties in "its ambitions and its dismantling of the principles of democracy and its institutions".

Apart from the coronavirus epidemic, other projects too call for unity, including electoral reform, the course of Slovenia's foreign policy, and the need to form a comprehensive concept of a green country.

Despite much effort that has been invested in the electoral reform, decreed by the Constitutional Court, including by President Borut Pahor, Kučan believes parties have embarked on the project in ill faith.

"Each party has calculated what would suit it best, even though the most suitable solution would be to abolish electoral districts and adopt a system that we have for elections to the European Parliament," involving a preferential vote.

Kučan is of the opinion that Slovenia's foreign policy is moving away from the guidelines passed by parliament with writings by Prime Minister Janez Janša and Foreign Minister Anže Logar, which were not the positions of the government.

He believes it will take quite a while for Slovenia to restore the "trust of the external world". "The uncertainty about Slovenia's international position and interests and its tarnished reputation in the world will also tarnish the authority of the Slovenian presidency of the Council of the EU."

"We're aspiring for friendship with those we shouldn't be friends with and have nothing in common with. Hearing arguments that us who used to live in the East have a different understanding of democracy and the rule of law than long-established democracies, it feels as if we are making fools out of ourselves," he said.

He believes Slovenia should have a balanced relationship with the superpowers - the US, Russia and China, and in the future he would like to see the country at the core of a successful EU as a major world player.

STA, 6 December 2020 - As Slovenia is about to mark the 30th anniversary of a referendum in which people nearly unanimously voted for independence, Lojze Peterle, the then prime minister, says the nation should focus on what unites it, while it will have to put WWII and post-war history behind if it ever wants to achieve understanding and progress.

Looking back on independence and the plebiscite, Peterle finds it crucial that DEMOS, the coalition of parties forming the first democratic opposition, won the first multi-party election in April 1990. "Had DEMOS not won at the time, there would have been no plebiscite," he told the STA in an interview.

Another key move was that his government started forming Slovenia's own armed forces as soon as it assumed office. "With the first line-up a week ahead of the plebiscite, we showed people that we have a real force to protect our determination for a free Slovenian state."

While the decision for the independence referendum was taken by the DEMOS leadership in the night between 9 and 10 November 1990, DEMOS invited the opposition to join in the effort and an agreement to that effect was signed 30 years ago, to the day.

"The result was that the law that formed the basis for the plebiscite was passed with no one voting against. The agreement sent out a strong message to the people of unity in Slovenian politics."

While he never doubted the result of the plebiscite, Peterle had not expected such a convincing outcome, with 88.5% of all eligible voters or 95% of those who cast their ballots voting in favour.

Such an outcome was important both "internally, because it prevented greater divisions, and externally because it gave the government the needed legitimacy in talks with Belgrade. The world had to acknowledge that too."

Peterle does not think a similar cross-party agreement is needed now as Slovenia is battling the coronavirus epidemic: "We have a democratically elected government that has the mandate, responsibility and the needed majority in parliament to implement its policies. There's no need for national consensus for every thing."

However, he says it is against national interests that "the opposition should be pressuring for one thing only at these difficult times - for change of power at all cost - especially given the fact that the previous government resigned".

"And now, for 30 years really, keeping all of Slovenia busy with allergy against Janez Janša, which has come as far as violent riots, it cannot be a statesman-like response to this government's work."

Still, he does believe politics should try to near positions on some points, such as overcoming divisions stemming from the past, which should be done with truthfulness and justice.

"There's not a single political meeting that wouldn't end with a debate on World War II and revolution, even though hardly anyone from that time is still alive.

"This is because we haven't processed and overcome it. Once we'll have to let bygones be bygones and head on. As long as we keep watching each other through the WWII and revolution gun pointers, there'll be no peace or progress."

He believes one of Slovenia's problems is a lack of structural change similar to other former Communist countries. "We formally introduced democracy, but in fact many things go on the old way (...)

"It's not just the right which finds that the rule of law doesn't work the best way. I'm even more worried about a lack of respect for the dignity of others and those who are different."

Touching on electoral reform, Peterle says the best way would be to redraw electoral districts: "If we abolish them, big urban centres and established faces from TV screens get most benefit.

"The existing system with electoral districts has made it possible for people to enter politics whom we didn't know as big politicians but whom people trusted to represent them. This quality of the electoral system should be preserved."

Peterle would also like to see more consensus in politics on foreign policy "rather than having the situation when one government goes to Washington, and the other to Moscow".

He does not think there is any major dilemma as to whether Slovenia should look to the Visegrad Group or to the core Europe.

"We're part of the core Europe as part of Central Europe with specific political, historical and cultural experiences and thus a different sensitivity, which means we see some things, including values, a little bit differently than they see them in Brussels.

"This is why I believe Brussels should work more on understanding why Central Europe is a little bit different. More dialogue is what's needed."

Slovenia can support that dialogue with creative proposals, which is why he welcomes PM Janša's letter to European leaders in reference to the rule of law and recovery aid.

"The letter doesn't boost the blockade but is aspiring to removing the blockade with a sensitivity for realpolitik. This is also how Angela Merkel understood it."

He believes tensions in Slovenia are largely a matter of money "when you hit a monopoly, a formal or informal structure that has roots in undemocratic times, everything is wrong.

"We introduced democracy to make change possible, so that corruption doesn't become entrenched. You don't solve things by calling them ideological, untouchable," he says.

STA, 25 October 2020 - Slovenia celebrates Sovereignty Day, a national holiday commemorating the day when the last Yugoslav People's Army soldiers left the country's soil in 1991 in one of the key events in the process of Slovenia's independence. In their messages on the occasion, the country's top officials evoked the nation's courage, resolve and unity of the time.

Prime Minister Janez Janša, who served as the defence minister at the time of historic events, recalled the spirit of the time, the courage and unity. "History teaches us that nothing is impossible if we stand united as a nation."

"The courage, wise decisions and the Slovenian nation's unity and connectedness through a shared idea allowed us, despite political differences and adversity by some, to win an independent country that generations before us had but dreamed about," said Janša in his written message.

Today's holiday should be a reminder of how unity on a common goal can keep Slovenians strong as a nation, Janša wrote, calling for fostering an awareness that together the nation can defeat what appears to be invincible and achieve what seemed unimaginable only a day ago.

He said that Slovenia's sovereignty and the momentous events almost 30 years ago should not be taken for granted.

"Slovenia did not have allies to lean on in the War of Independence (...) We could only rely on ourselves - our knowledge, abilities, and our resolve to have our homeland. At the same time we also hoped for a little bit of God's blessing," said Janša.

Praising the emerging Slovenian Armed Forces, the Slovenian police and patriots, for defeating the Communist Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), and lauded the courage and bravery displayed at the time.

"It is with deep respect that we watch the footage of hour compatriots from the Vipava Valley and elsewhere taking on JNA tanks with naked fists," he said, adding that it took not just civic courage but also wisdom to defeat what at the time was considered the world's tenth most powerful army.

What made the effort even more noble and honourable was that the Slovenians attended to the wounded JNA soldiers on a non-discriminatory basis and did not take revenge on the aggressor soldiers "not even when they were departing with bowed heads", nor did the war result in a massive flight of refugees.

"This made our goal, the realisation of the Slovenian nation's plebiscite decision in favour of an independent and sovereign country even brighter and nobler. It will remain written down in history for ever as proof of the maturity of the Slovenian nation and the courage of its soldiers," said Janša.

Similarly, Parliamentary Speaker Zorčič remembered the courage and the commitment to the same goals and values displayed at the time, but he also called on the nation to demonstrate the same resolve, confidence, understanding, solidarity and unity in taking on the coronavirus pandemic.

He said that the Slovenians were being weakened in their fight against the unprecedented pandemic "not just by its underrating, but also by our disunity over the measures against it" and the creation of false impression by some that those measures were aimed at suppressing democracy.

"Today, we are fighting a new, invisible enemy that we will not surrender to. The uneasiness of masks will not move into our hearts. It is time that like 29 years ago we proved again our ability to be strong, confident, understanding and sympathetic," the speaker said in his message.

The public holiday, which is not a work-free day, was declared by the National Assembly in 2015 in remembrance of the day in 1991 when the last remaining Yugoslav Army soldiers departed from the port of Koper aboard a ship.

The withdrawal is considered one of the final steps in the independence efforts, coming after Slovenia declared independence on 26 June, whereupon the Ten-Day War broke out when the Yugoslav Army launched attacks from its barracks on 27 June.

The armed conflict was followed by talks which resulted in Slovenia agreeing to a three-month moratorium on independence implementation as part of what is known as the Brijuni Declaration.

As the moratorium was about to expire, Yugoslavia's authorities realised it would be impossible to keep Slovenia in the federation. Preparations thus started for the army's withdrawal from Slovenian territory.

The stated purpose of the holiday is to stress and emphasise the importance of Slovenia's sovereignty and to strengthen the respect of human rights and fundamental freedoms.

There was no formal ceremony this year but President Borut Pahor address the people alongside the military commander of the Territorial Defence during the independence war, Janez Slapar, and the Chief of the General Staff of the Slovenian Armed Forces, Brigadier General Robert Glavaš.

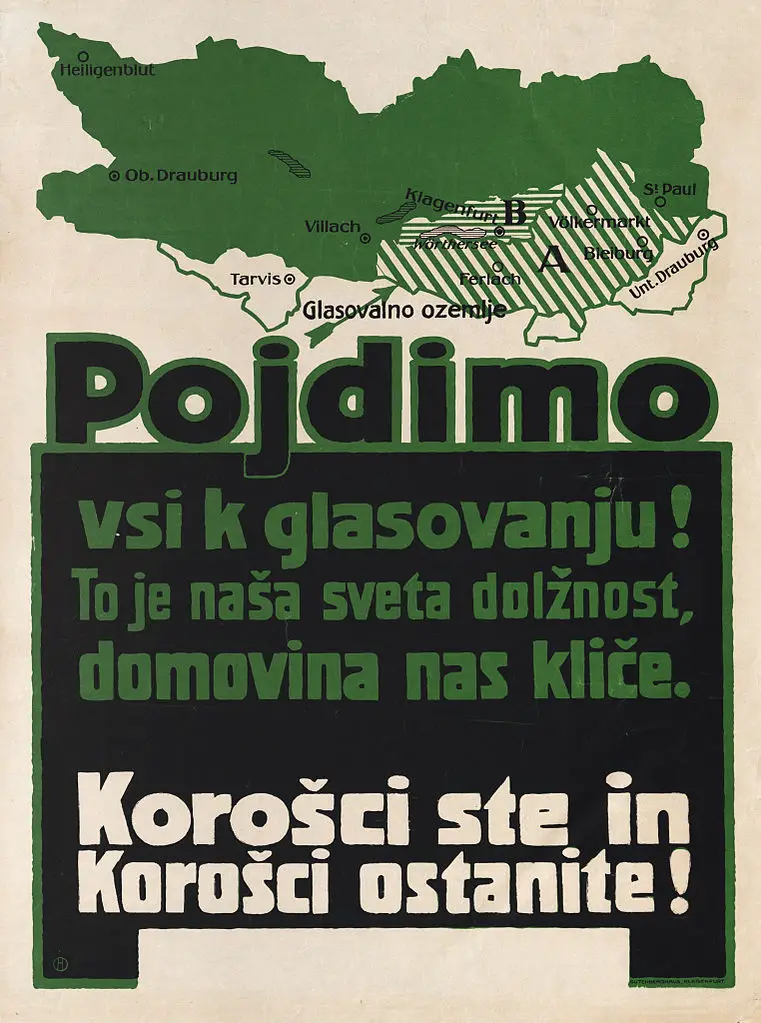

STA, 8 October 2020 - Two years after the end of World War I, a Slovenian minority would end up on the other side of the Karawanks following a plebiscite in Carinthia that determined the border between Austria and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. While the outcome of the vote was the product of several factors, what followed was a period of revanchism.

The plebiscite was held on 10 October 1920 under the provisions of the Treaty of Saint-Germain, signed a year earlier by the allied powers that won World War I on the one hand and the Republic of German-Austria on the other.

While parts of Carinthia now in Slovenia (Meža Valley and Jezersko) were to be incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, the fate of southern Carinthia down to the Klagenfurt basin was to be determined by a plebiscite, under the principle of self-determination championed by US President Woodrow Wilson.

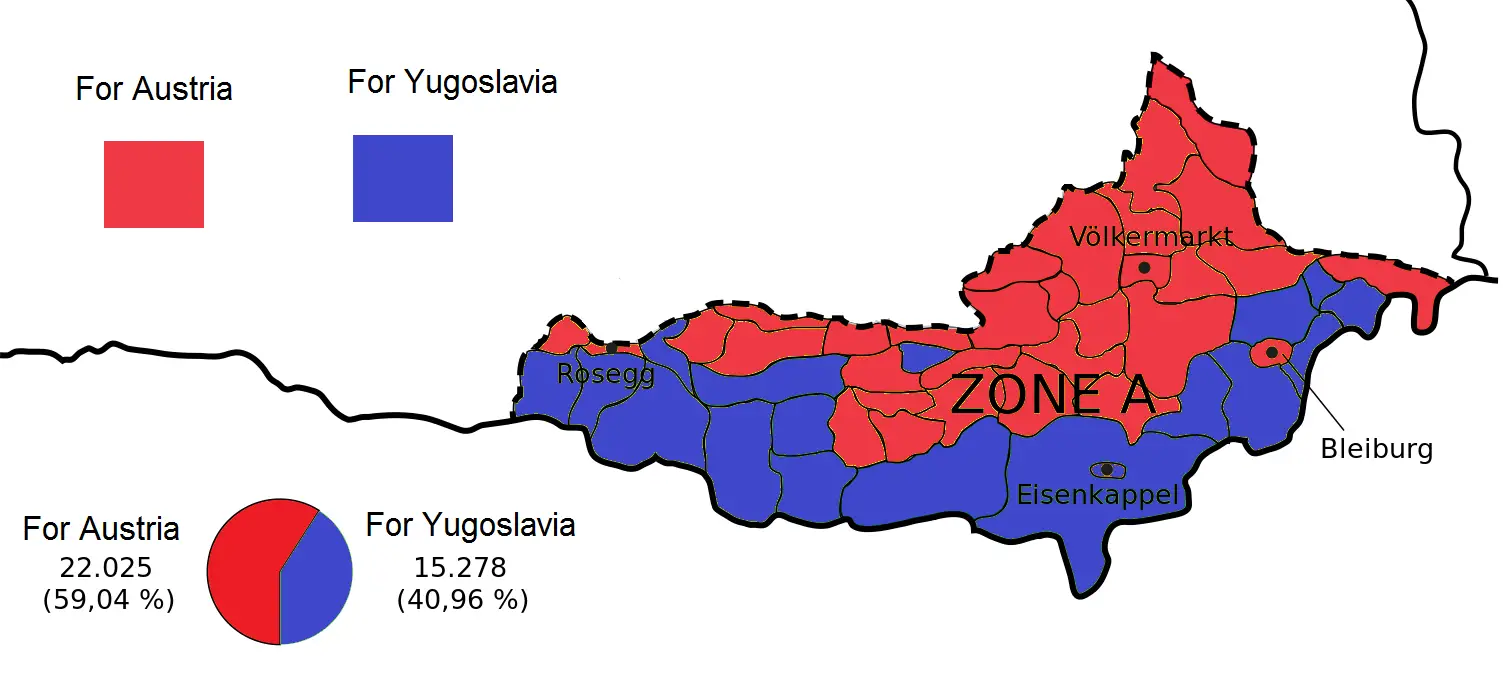

Before the vote, the Klagenfurt basin was divided into two zones; Zone A in the south with a predominately Slovenian speaking population and the smaller Zone B, which comprised Klagenfurt and its surroundings. Zone B was to hold a referendum only if a majority of voters in Zone A would have opted for what had already at the time been known as Yugoslavia.

However, with the turnout at almost 96%, 22,025 ballots or 59.04% of the vote cast was in favour of Austria, against 15,279 or 40.96%, who opted for Yugoslavia.

In their 2003 textbook, historians Dušan Nećak and Božo Repe estimate that at least 10,000 Carinthian Slovenes voted in favour of Austria, while some historians estimate a majority of the Slovens eligible to vote opted for Austria.

Despite having posted military victories ahead of the plebiscite, the Slovene side suffered a diplomatic defeat at the Paris peace conference and another one at the ballot box.

Poster in Slovene ("Let us go and vote! It is our sacred duty, our homeland is calling us. You are Carinthians, and you should remain Carinthians!"), featuring zones A and B. (Wikipedia)

A mix of factors and interests decided the outcome

Historian Andrej Rahten, a former Slovenian ambassador to Austria, says that several factors were at play in the outcome of the plebiscite, however the battle for Carinthia had already been lost during the Habsburg monarchy.

"Even before World War I, Slovenians in Carinthia saw an adverse demographic trend, going from one quarter of Carinthia's population in the 1900 census by speaking language, which was biased methodologically, to a good fifth in 1910, and then, in the first post-plebiscite census in 1923, to one tenth."

Rahten, talking with the Slovenian and Austrian press agencies, STA and APA, in a joint interview, says the key role in the decision for the plebiscite was played by US President Thomas Woodrow Wilson.

If it had not been for France's support of Yugoslavia, the demarcation would have been even more harmful for Slovenians, he says; if you asked the Americans, they would have assigned Carinthia north of the Karawanks to Austria even without a plebiscite.

This was because of the belief that Austria, which had to accept secessions of some other border territories with practically no referendum rights, should be given some territorial concession lest it should become part of some great Germany.

Rahten believes the plebiscite result would have been very different had it not been for the Karawanks mountain range, which represented not only a physical but also a psychological barrier.

"The decisive element was economic reasons"; for centuries Klagenfurt and Villach had been traditional markets for Carinthian farmers, while now they were supposed to be replaced by Ljubljana.

Similarly, British historian Robert Knight offers economic interests as one possible explanation why Slovenians opted for Austria, along with the appeal, or lack thereof, of Yugoslavia with respect to Catholicism or the monarchy.

The Austrian propaganda played an important role; it emphasised economic benefits of the undivided Klagenfurt basin, regional identity, links between Slovenian- and German-speaking inhabitants and the cultural differences between Catholic Austria and Orthodox Serbia as the leading nation in Yugoslavia.

Historian Tamara Griesser-Pečar, in one of her articles, also notes the significance of the Carinthian Slovenians' attachment to their land, as well as social, economic, religious and political reasons and their bad experiences with the Yugoslav authorities.

The results by municipality. Paasikivi CC-by-SA-4.0

After plebiscite, broken promises and revanchism

A vital factor why Slovens opted for Austria would have been Austria's pledge to protect the minority's rights, passed by the provincial assembly in Klagenfurt in September 1920.

However, as early as 25 November 1920, Arthur Lemisch, the head of the province's provisional government, publicly advocated in the provincial assembly for Carinthian Slovenians to be Germanised within a generation.

The nationalist sentiment in Austria only grew between both world wars, resulting in further assimilation of Carinthian Slovenians. It was not until 1955 that they had their rights guaranteed in the Austrian State Treaty but they are yet to fully enjoy them.

Rahten and Knight, a historian from University College London who has studied the fate of Carinthian Slovenians, have talked to the STA and APA about the dark period in the wake of the plebiscite, about revanchism, persecution and scaremongering.

The Slovenians who voted for Austria were expected to assimilate, become German, while the others had to be induced to move south through a mixture of "pressure, persuasion and structural coercion", says Knight.

There were also opposing forces as for example in Social Democracy, "but by and large, Carinthian politics was also aimed at intolerance, exclusion and ethnic homogenization", although Knight does not see that as something distinctly Carintihan.

"The plebiscite definitely made the tensions only worse and it took decades, through change of generations, for those first months of revanchism to be gradually and slowly put behind," Rahten says.

He notes physical assaults on people accused to have voted for Yugoslavia, even if they may have not, arson attacks on the homes of Slovenian patriots, and the perpetrators going punished.

Before the plebiscite, Carinthian officials had been promising that no one would be hurt, that everyone would enjoy equal rights, that Slovenians would be better off than in the old Austria, but just the opposite happened.

"The promises were soon broken. What followed soon after can simply be called revanchism (...) which led to the Slovene elite being driven out of Carinthia," says Rahten, noting that an estimated 3,000 refugees fled Carinthia after the plebiscite.

At the same time, "the political impotence when it came to protection of the Slovene minority's rights in Carinthia was offset by very harsh measures taken against the Germans who were left in Yugoslav Slovenia", such as forced Slovenisation of German schools.

Centenary celebrations in a buoyant mood

The relationship between the majority and minority in Austrian Carinthia had begun to mend only after Slovenia declared independence in 1991 where Austria played a key role in the country's international recognition.

Like in the case of the Slovenian minority in Italy, the atmosphere for the minority in Carinthia improved further after Slovenia joined the EU in 2004 and the Schengen area three years later.

Knight, noting that the centenary celebrations appear to have taken a different course after neglect of the Slovenian minority and its language in the past, believes the main emphasis of commemoration of 1920 should be on honouring the promise made publicly on the eve of the vote, that is to preserve the minority's unique identity.

STA, 6 September 2020 - Four victims of fascism, known among Slovenians as Basovizza Heroes, were remembered with a ceremony on Sunday at the site where they were executed 90 years ago following a short trial before a Fascist court in Trieste.

Slovenian patriots Ferdo Bidovec, Fran Marušič and Alojz Valenčič as well as Zvonimir Miloš, a Croat with close links to the Slovenian community in Trieste, were executed on 6 September 1930 in Basovizza common.

They were sentenced to death in what is known as the First Trieste Trial for an attack on the newspaper Il Popolo di Trieste. The other 12 defendants were sent to prison.

Tried under Fascist laws, the four are still formally "terrorists", something their relatives would like Italy to change, especially because the other Slovenian patriots and antifascists sentenced to death at the Second Trieste Trial in 1941 were posthumously rehabilitated.

The Slovenian ethnic minority in Italy cherishes the memory of Basovizza Heroes with annual commemorations, which are also often attended by Slovenian officials.

The victims of the first and second Trieste trials were also posthumously honoured with Slovenia's Golden Order of Freedom for their fight against Nazism and Fascism and for loyalty to Slovenian identity in the darkest times of Italianisation.

What is one of the highest state honours was bestowed on them in 1997, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the reunification of Primorska region with Slovenia.

In July, President Borut Pahor and Italian President Sergio Mattarella visited the Memorial to Basovizza Heroes alongside paying a visit to the Foiba of Basovizza, a karst pit which for Italians symbolises post-war summary killings by Partisans.

The move was seen by some as an act of reconciliation between the nations which had been on the opposite sides in the past, and as a revision of history by others.

Today's commemoration was addressed by Slovenian parliamentary Speaker Igor Zorčič, by Marija Bidovec, Ferdo Bidovec's niece, by Peter Močnik, a secretary of the SK Slovenian minority party, and by the head of the regional institute for the history of WWII resistance movement, Mauro Gialuz.

Addressing a sizeable gathering, Zorčič said the Basovizza Heroes had become a symbol of resistance to a murdering and oppressive regime and ideology that incited hatred and violence among people. They are heroes of the free Europe built on the foundations of anti-Fascism and resistance to all ideologies in the name of which people oppressed and killed each other.

The ceremony was attended by people from both sides of the border, including several senior officials, among them Minister for Slovenians Abroad Helena Jaklitsch, Slovenian Ambassador to Italy Tomaž Kunstelj, General Consul in Trieste Vojko Volk and Slovenian senator in Rome Tatjana Rojc.

In his address, Trieste Mayor Roberto Dipiazza said he did not deem the Basovizza Heroes terrorists. He mentioned Pahor's and Mattarella's joint visit to the Basovizza memorial and foiba and the symbolic return of Trieste Hall among the gestures that he said inspired hope for the future among the Slovenian and Italian communities.

Several other speakers noted the latest events as a new piece in the puzzle of reconciliation between the two nations and called for full rehabilitation of the Basovizza Heroes.

Later in the evening Archbishop of Ljubljana Stanislav Zore was to say mass at the local parish church, whereas Italian Senator Tatjana Rojc, a Slovenian minority member, delivered a speech.

The four patriots were also remembered in Slovenia with two commemorations on Friday, one in front of the University of Ljubljana and the other at the memorial to Basovizza Heroes in Kranj.

Historian Štefan Čok spoke about the values and message of Basovizza on Saturday at the memorial in Basovizza, and a number of events are planned for next week.

One of the highlights will be the presentation of Milan Pahor's book about Borba, an underground organisation whose members the four Basovizza victims were.

STA, 24 August 2020 - In Kočevski Rog, a vast forest area riddled with chasms in the south-east of Slovenia, known for being a site of post WWII-executions, archaeologists have retrieved the remains of about 250 victims from a mass grave uncovered in May. Most of the victims were young men, mainly civilians, killed in the autumn of 1945.

Presenting the findings in Ljubljana on Monday, the government commission for mass graves said that the remains had been retrieved from Chasm 3, as the grave has been termed, in July.

Archaeologist Uroš Košir said that his team found a large amount of ammunition in the chasm and along its outer edges, leading them to believe that executions were conducted on the spot.

Analysis of entry and exit wounds found on sculls has show that the victims had been killed with automatic rifles. Remains of at least six different hand grenades were also found in the chasm, as well as several unexploded devices.

Related: Mass Concealed Graves in Slovenia, an Interactive Map

Bodies were covered with rocks and debris, however, the excavation team also found bodies on top of these. "We suspect these were captives tasked with covering the chasm, but later ended up inside as well," said Košir.

Preliminary anthropological analysis results show that the remains belonged to about 250 individuals, mostly civilians. All victims were over 15 years old, quite a few were in their early 20s.

Most of the victims were men. While female remains have been found, the team believes there were no more than five women in the grave.

About 400 buttons were found, mostly civilian, some textiles, spoons, combs, mirrors, personal belongings, rosaries and lockets, mostly Slovenian. Newspaper scraps were also found in the grave, said Košir.

Pavel Jamnik, the head of the police campaign dubbed Reconciliation, said today that they had first been made aware of this grave in 2002, but had then been looking for it some 500 metres away.

Zdravko Bučar, the head of the Novo Mesto Cavers' Club, said the 14-metre chasm was found due to a map deviation.

Jamnik said that an analysis of prisoner records in relation to local prisons by the former Yugoslav security and agency OZNA showed that in September of 1945 a selection was made among Novo Mesto prisoners. While some were freed, others were taken to be killed, some of them had definitely been taken to this site.

While selections were made by OZNA, transports were carried out by KNOJ, Jamnik said. The commission had previously talked to a former member of KNOJ, a corps of the Yugoslav Partisans in charge of internal security, who had transported prisoners to designated locations, where they were handed over to Partisans speaking Slovenian and other Yugoslav languages.

Jože Dežman, the commission president, said that the Kočevski Rog killings had taken on new dimensions in recent years. While the chasm Pod Krenom seems to be the grave of Serbian and Montenegrin victims, the chasm in Macesnova Gorica seems to hold Slovenian victims.

Dežman believes that Chasm 3 could provide some indication as to what had happened to the Novo Mesto Homeguard, a group of several thousand who failed to flee after World War Two.

You watch a discussion on post-WW2 massacres in Slovenia featuring the authors of Slovenia 1945: Memories of Death and Survival After World War II here