Ljubljana related

STA, 9 May 2020 - Russian Ambassador Timur Rafailovic Eyvazov laid a wreath at the site of a former Nazi prison camp in Maribor on Saturday in memory of several thousand Russian prisoners of war who died there. He said keeping the memory alive was important to prevent history repeating again.

The building of the former Stalag XVIII D camp is being turned into a museum after the Maribor municipality has bought the plot from a private owner, while Russia is to provide the funding to create a museum.

Additional exhibition material was put on show on the occasion of Victory Day to bear witness to the developments there during Second World War.

The exhibition is expected to open to broader public in the autumn, which would make it a real museum after it has so far been open only on special occasions and mostly only to professionals.

#VictoryDay #ДеньПобеды

— Russian Emb/Slovenia (@AmbrusSlo) May 9, 2020

Veleposlanik Rusije Timur Ejvazov, župan mestne občine Murska Sobota, vodstvo ZZB NOB in društva Slovenija-Rusija so položili vence pred spomenikom sovjetskemu vojaku in jugoslovanskemu partizanu v Murski Soboti. Slovesnosti so potekali tudi v Mariboru pic.twitter.com/Mn5d3oSsUs

Ambassador Eyvazov, who took office in Slovenia in January, reiterated his country's commitment to the project. "We still don't know how many people died here, but the figure must have been very high. The facility is exceptional because it has remained untouched," he told reporters.

"The project is exceptionally important in particular for the younger generations to learn the truth about the horrendous crimes that were being committed here 75 years ago. It's important to make sure such horrific history will not be repeated again." said the ambassador.

During WWII, the complex of a defunct customs warehouse in the Maribor Melje borough was part of a German Nazi prison camp. Between September 1941 and March 1942, it held several thousand Russian POWs in extremely inhumane conditions and most of them died there from exhaustion, starvation or disease.

The search through various European archives has so far yielded close to 3,000 names of Soviets who died in the camp. "We want to press on to find all 5,000 names of the Soviet POWs killed," said Janez Ujčič, director of the International Centre for WWII Research in Maribor, which manages the museum.

The plan for the museum was unveiled in 2014 during a visit by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov but it has so far hosted only dedicated conferences. A one-storey hall, the complex does not have basic infrastructure such as electricity or toilets, but this should be tackled by autumn.

"Today's Victory Day ceremony represents the first step to museum activity in this former camp. With the present exhibition we've launched a lasting renovation of this complex," said Ujčič, adding that the museum had sparked a lot of interest in the international expert community as well as in Russian media.

The three-part exhibition chronicles Maribor's resistance in 1941, the city's German occupation, the tragedy of the Russian POWs in the camp and the joint struggle of the Rad Army and Partisan resistance movement in the former Yugoslavia.

John Bills is the author of four books on Europe's better half, electronic versions of which are currently available at special lockdown prices, including a great deal on all four - just under £10 (or just over €11) for the lot with the promo code ENDOFDAYS at poshlostbooks.

Slovene history is littered with no shortage of talented writers. Quite the opposite, in fact, and I’d wager that this small chicken-shaped land has produced more wordsmiths per square kilometre than any other country in Europe. Fertile ground for the eloquent, that’s for sure. Every period of the nation’s history features men and women who have excelled in storytelling, taking the events and circumstances of the time to fashion tales that are as vital today as they were then.

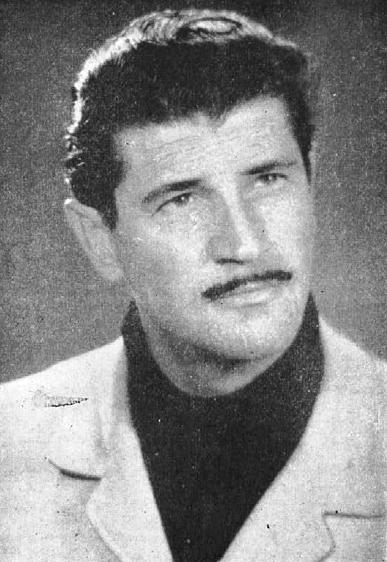

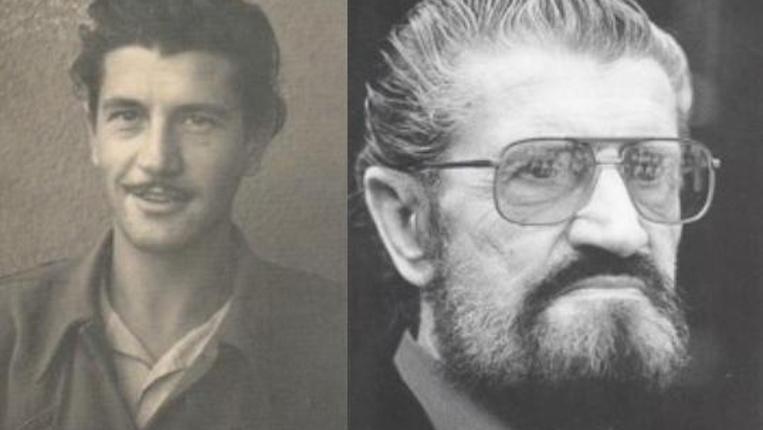

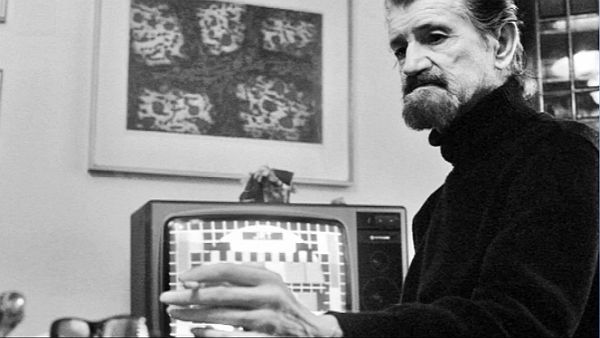

The writer has many jobs, many roles that must be played in the theatre of everyday life. Entertainers for sure, there must always be an engagement, but books go beyond mere titillation. Ljubljana-born Vitomil Zupan said it best in Leviatan (Leviathan [obviously]), an epic piece of work that details the day to day existence inside a Yugoslav prison; “…the wordsmith must be a chronicler of his times, and a chronicler must not be disgusted by anything”. In Zupan’s era, there was a lot to be disgusted by, but the modernist man turned his nose up at not a thing. In doing so, he became one of Slovenia’s most celebrated 20th-century writers, a man famed for his unwavering obsession with the edges of existence, his rapacious sexual appetite and a steely charm that positively bellowed “Hi, I’m your mum’s new boyfriend”. His life was eventful in all possible ways, but it was also a fascinating picture of Slovene creativity in those early Yugoslav days. Stigma, expression, productivity and oppression, repeated.

Vitomil Zupan was born just a couple of months before World War I began, and it didn’t take long for his life to encounter turbulence. His father was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian Army, and the Habsburg force had a pretty wretched record over the first years of the Great War. Casualties were high, and Mr. Zupan was one of the dead. Young Vitomil lived through the war and was a creative schoolchild, but his restlessness and ability to seek out trouble often, well, got him into trouble. The apex of this was a game of Russian Roulette gone wrong, a game that took place when Vitomil was just 17. His hand was on the trigger, his friend’s body was at the end of the barrel, the chamber was loaded. Russian Roulette is one of the few games that go wrong by going right. Zupan was expelled from school (a fairly light punishment, in hindsight), and he chose to hit the road.

Vitomil travelled long and far, crisscrossing the Mediterranean in search of new experiences and fresh excitement. His was a true vagabond existence, jumping from city to city and job to job, meeting people and moving on as often as was necessary. He worked as a sailor, a house painter, a ski instructor and more, even having a stint as a boxer. A strong jaw will take you far, never forget that. Zupan moved from Europe to the Middle East and North Africa, learning languages, cavorting with foreigners, learning how to thrive in new environments and in unfamiliar surroundings. Remember kids, if you can travel, travel.

Zupan returned to Ljubljana and continued his education, but he spent more time studying medical textbooks than concentrating on his own studies, feeding a constant need to understand his own emotions and tumultuous moods. The latter was dramatically exacerbated by the onset of World War II, which makes a lot of sense. Zupan immediately joined the Liberation Front and fought against the Italians, experiencing a number of battles before being captured and arrested. He was first sent to Čiginj concentration camp (near Tolmin), before being moved to the newly-opened Gonars camp in the north of Italy.

Established in February 1942, Gonars was a fascist camp specifically for Slovenes and Croats, people the Italians deemed ‘inferior’ and ‘barbaric’, those living in borderlands that Mussolini had his seedy eyes and grubby hands on. 5,343 men, women and children (1,643 children, to be precise) arrived just two days after it was opened, and the transports continued from there. Some of history’s most notable Slovenes were among them, men such as Jakob Savinšek, Bojan Štih, France Balantič and many more. Vitomil Zupan was another.

Vitomil Zupan managed to escape Gonars, and he immediately joined the growing Partisan movement Slovene, initially fighting on the frontlines before moving into the cultural department. He wrote plays that championed the socialist cause, encouraging Yugoslav patriotism in his fellow fighters and providing much-needed escape along the way. Following the war, he was rewarded with honours and a position at Radio Ljubljana, before the holy grail of a Prešeren Award for his novel ‘Birth in a Storm’ in 1947. Then Yugoslavia and the USSR had the big falling out, and it all went to the dogs.

Zupan himself put it best when he said that ‘there comes a time when one man can ruin ten people, but ten people can’t help one man’. The split filled Yugoslavia with pride, it was making its own way after all, but it also filled the halls of power with neurosis and paranoia. The national liberation, the class revolution that followed and the eventual split from the Soviet Union, these were holy subjects that were nigh on untouchable. Zupan was one of the few people honest enough to mention the shades of grey, to point out that everyone can be involved in a revolution but not everyone becomes a revolutionary, which explains the prisons. Those prisons would soon host Vitomil Zupan.

Truth be told, he was an easy target. He was a controversial cultural figure, one who was openly and passionately in touch with the more erotic desires of the mind, a man who had travelled extensively, spoke multiple languages, was comfortable in the presence of foreigners and was ruggedly handsome to boot. Oh, and that whole ‘shooting his friend’ thing. Zupan was sentenced to 15 years in prison, a term that was almost immediately increased to 18 because of his conduct in court. To prison he went, less for his ideas and more for who he was, what he knew and who he knew it about. There was no evidence, and barely any more of a defence.

Zupan only served seven of his 18 years, but don’t make the mistake of thinking that the experience was full of cheer. His already-compromised health took a turn for the worse, and for years he wasn’t allowed to read or write. He worked around these restrictions through character, ingenuity and how poorly-policed the jails were, compiling enough ideas and notes for one of his most famous pieces of work. Published in 1982, Leviatan (Leviathan) is a narrative of this time in prison, a torturous study of humanity that covers day to day atrocities, sexual frustration and release, violence, boredom and no small amount of black humour. The novel doesn’t really have a story outside of ‘this is what life is actually like in prison’. It is a vital piece of work.

Zupan’s major break came seven years prior, with the much-loved Menuet za kitaro (A Minuet for Guitar). This novel focused on his time in the war, a book based half during that conflict and half in the more relaxed atmosphere of a 1970s Spanish holiday resort, where soldiers from opposing sides (a Slovene Partisan and a Nazi) try to make sense of the whole thing. It covers all sides and all interpretations of the war and is every bit as ambitious as that suggests, and features one of the most pathetic, banal, poignant and perfect character deaths in the history of conflict fiction. It was adapted for film in 1980, given the new moniker Nasvidenje v naslednji vojni (See You in the Next War) in the process. A second Prešeren Award came in 1984, this time for his entire body of work.

There is a disjointed feel to Vitomil Zupan’s life story, a collection of contradictions that only seem to happen to those tasked with chronicling history in fictional form and blessed with the ability to do so. He was arguably more successful than any other persecuted writer from what was Yugoslavia. He won awards, experienced commercial and critical success, yet no publisher would go near his work in its original form. He wrote the most expressive Slovene books of his generation, but almost all of these works were heavily censored by the humdrum and the grey. He lived a life of tumult, adventure and penury, but everything seemed to happen to him so that he could write about it.

Vitomil Zupan died in Ljubljana on May 14, 1987 (the same day as Rita Hayworth, believe it or not). One of Slovenia’s most important and influential modernist writers, he is to the Slovene literary canon what Hemingway and Solzhenitsyn are to the west, combined. Such lazy comparisons are often difficult to avoid, especially when the stern eyes and imperturbable moustache of Vitomil Zupan, your mum’s new boyfriend, gaze in your direction.

John Bills is the author of four books on Europe's better half, electronic versions of which are currently available at special lockdown prices, including a great deal on all four - just under £10 (or just over €11) for the lot with the promo code ENDOFDAYS at poshlostbooks. You can enjoy more of his work on Total Slovenia News here.

STA, 6 April 2020 - Slovenia is marking this week 30 years since holding its first free multi-party elections. The winning coalition of parties that formed an opposition to the Communist Party and its affiliates, would lead the country to independence a year later. Speaking today, two officials elected at the time say the country has not realised its full potential.

The late 1980s Slovenia, then still part of Yugoslavia, saw a buzz of burgeoning efforts by scholars, authors, cultural workers and some politicians pushing for the country to introduce a pluralist democratic system and market economy and to break away from the socialist federation.

Gathering momentum through a series of landmark events such as the publication of a manifesto for Slovenia's independence in the 57th volume of the literary journal Nova Revija, the JBTZ trial and the mass protests it triggered, the May Declaration calling for independence and the Slovenian delegation's walking out of the Communists of League of Yugoslavia, the campaign led to the first multi-party election on 8 April 1990.

On that day voters picked two-thirds of the delegates to the 240-member tricameral Assembly; 80 delegates to the socio-political chamber as the most important house, and 80 delegates to the chamber of local communities, with the election to the chamber of "associated labour" following on 12 April.

Of the 83.5% of the eligible voters who turned out, 54.8% voted for DEMOS, the Democratic Opposition of Slovenia, who brought together the parties that had been founded in the year and a half before as part of the democratic movement that demanded an end to the one-party Communist regime. DEMOS formed a government which was appointed on 16 April with Lojze Peterle as prime minister.

The winner among individual parties was the League of Communists of Slovenia - Party of Democratic Renewal (ZKS-SDP), the precursor to today's Social Democrats (SD). The party won 14 seats in the socio-political chamber, which would evolve into today's lower chamber, the National Assembly.

However, with the exception of the chamber of associate labour, DEMOS won a convincing victory in the then Assembly, winning 47 out of the 80 seats in the socio-political chamber, of which 11 were secured by the Slovenian Christian Democrats (SKD).

Along with parliamentary elections, Slovenians also cast their vote for the chairman and four members of the collective presidency. Milan Kučan, the erstwhile Communist leader, was elected chairman after defeating DEMOS leader Jože Pučnik in the run-off on 22 April with 58.59% of the vote. Matjaž Kmecl, Ciril Zlobec, Dušan Plut and Ivan Oman were elected members of the presidency.

Looking back, Plut says the time of Slovenia's first democratic election marked two sets of political change; the political system's change to democracy and the country's becoming independent. The party that would not support those two key goals had little chance of wining voters' trust, he has told the STA.

Plut led the Slovenian Greens, the party that won 8.8% of the vote in the 1990 election, which he says was the highest share of the vote among all green parties in Europe. He believes the reason the Greens would not repeat the feat again was that the right-wing faction prevailed following the party's joining DEMOS, which meant a party naturally favoured by left-leaning voters lost its voter base.

Asked whether the situation would be different today had Pučnik won the presidential run-off, Plut does not think it likely: "The voters had obviously made a well thought-through decision for a balance. DEMOS won the assembly, while Kučan was elected presidency chairman. The latter had a host of political experience, which came very handy at the time."

"Could anything be different? I don't know. We can only guess," Kmecl says when offered the same question. Kmecl, a Slovenian language scholar, literary historian and author, remembers the time of the first democratic election as euphoric, "however, it hasn't brought what we all thought it would".

Above all, he had expected more solidarity. "Instead, it all ended in terrible egotism. I have always argued that neo-liberalism is harmful for small entities such as the Slovenian nation because it works only by the logic of quantity and power."

Plut agrees that not everything went the way it should have following independence. Most of all, he believes that Slovenia has failed to capitalise on its position as the most successful of all post-social countries in terms of economic indicators at the time.

"The entire politics, DEMOS included, soon forgot the key motive behind independence - increasing the prosperity of Slovenia's citizens. Hence the rapid increase in social and regional differences. There's no coincidence that public opinion polls show Slovenia hasn't realised the potential of independence," says Plut.

"In politics in general, the interests of individual political parties have too often been more important than people's prosperity. There's a lack of awareness that it is the politicians who are responsible for people's prosperity," says Plut.

All our stories tagged Slovenian history are here

STA, 28 February 2020 - The arson of the Trieste National Hall (Narodni dom) by the Fascists a century ago marked the start of a painful period for the Slovenian community that ended up on the Italian side of the border. A documentary shedding light on that event and what followed will premiere in Ljubljana tonight.

"It's a painful and often overlooked and too often simplified story about our western border and about Primorska. The arson of National Hall was the start of that cruel story and I dear say the beginning of Fascism in Europe," the author of Arson (Požig) Majda Širca has told the STA in an interview.

The Trieste National Home was built in 1904 to the design of architect Max Fabiani (1865-1962). It was commissioned by the Trieste Savings and Loan Society; as a Slovenian cultural centre, it was home to a theatre, hotel, savings bank, a ballroom, a print shop; most Slovenian associations.

"Trieste at the time of Austria-Hungary was a multi-cultural city in which various nations and cultures lived together. By building the National Hall, Slovenians made it clear they weren't going to build churches like other nations. They decided to build a space of multi-cultural dialogue (...)"

"Slovenians knew they needed a representative, visible and effective place in the middle of Trieste. Slovenians at the time lived on the city's outskirts, in small villages. They were a rural population that supplied Trieste but they didn't have their visible place in the city centre," Širca said.

The project was a thorn in the flesh of bigots who looked down on Slovenians, calling them schiavi (Italian for slaves). After the end of First World War, tensions escalated in Trieste, with a number of rallies held.

On 13 July 1920, one of those rallies escalated into a violent conflict in which shouts were heard that a Slav had killed an Italian. A mass of people then stormed the National Hall and torched it, historian Kaja Širok says in the film. Witnesses say that police and army officers stood by watching.

"That event later went down in history as 'the Slavic Crystal Night'. On that day several stores, print shops and buildings owned or managed by Slovenians were torched," the historian said.

Badly damaged in the fire, the National Hall was rebuilt between 1988 and 1990 and now houses the headquarters of the college of modern languages for interpreters and translators, part of the University of Trieste, as well as a Slovenian information centre.

The Slovenian community has been unsuccessfully trying to get back the building, with their hopes placed in this year's centenary when the presidents of Slovenia and Italy, Borut Pahor and Sergio Mattarella, are expected to meet in Trieste to mark the anniversary.

The film Arson also features excerpts of old comments by Boris Pahor, the 106-year-old Slovenian writer from Trieste who witnessed the National Hall arson and has often spoken out about the issue and has often said that Fascism in Europe started with that arson.

The year the National Hall went up in flames Slovenian territory was subject to barter, Širca says. Under the Treaty of Rapallo, signed in November 1920 by the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia) and the Kingdom of Italy, a third of Slovenian ethnic territory was awarded to Italy.

Ethnic Slovenians were put under huge pressure, faced assimilation attempts, denial of their language and territory, turbulence which Širca seeks to portray in her documentary, although she believes each of the key events included would merit a film of its own.

The film traces individuals' stories to the Basovizza victims, the Slovenians that were the first victims of fascism in 1930, the Fascist and Nazi occupation, the concentration camps and executions, the 1975 Treaty of Osimo and the establishment of a new border between Slovenia and Italy.

The documentary also touches on the foibe, the Karst pits where the victims of post-WWII reprisals by Yugoslav Communists were thrown.

"If you visit Basovizza, there are two monuments there not far from one another. One is an Italian monument to foibe, where every year the complex and complicated history of this space is sadly drastically simplified and abused, and the other a monument to the Basovizza victims.

"There's 15 years of history between the two, but I believe it always needs to be read in the context of that space. You cannot isolate one event from the other, just like you cannot but link the things together," said Širca, who served as Slovenia culture minister between 2008 and 2011.

She is concerned about what she sees as a dangerous loss of memory in Slovenia and elsewhere: "We know the past is being adapted, history is being horse traded and facts are being dressed in new clothes. Like in the past the new clothes are better worn trendy and we know how hard such simplification of history hits the Slovenian community."

The film, which will premiere at the National Museum of Contemporary History before being shown on TV Slovenija on Sunday night, is her contribution so that younger generations should learn about that difficult and multi-layered history: "If someone drums but one truth into their heads, it sticks. It's what is happening in the world today."

STA, 31 January - Slovenian WWII veterans intend to ask the Constitutional Court to review the recently annulled 1946 guilty verdict of Leon Rupnik, a Nazi collaborationist general. The Association of WWII Veterans is also considering appealing at the European Court of Human Rights.

It said "several people have turned to us who were direct victims of the Domobranci militia's cruel terror dictated by Leon Rupnik in collaboration with the occupying forces of Slovenian lands".

The association said in a press release on Thursday that it had also urged Human Rights Ombudsman Peter Svetina to take action to protect the victims' dignity.

Its president Marijan Križman called on Svetina last week "to not let the collaboration with the occupying forces be honoured in Slovenia".

Križman wrote to Svetina that due to the Supreme Court's unreasonable annulment of the verdict, the association members "feel hurt and expect action".

Pro-Nazi General Rupnik (1880-1946) was sentenced to death by court martial and executed in September 1946 for treason and collaboration with the occupying forces.

The Supreme Court, petitioned in 2014 by Rupnik's relatives, annulled the verdict for being insufficiently explained, and sent the case into retrial.

Rupnik's relatives could petition the Supreme Court on a point of law on the basis of changes to the penal code passed in the 1990s, after Slovenia gained independence.

The changes introduced an extraordinary legal remedy to rehabilitate those who were unlawfully or unjustly sentenced under the former communist regime before 1990.

However, the deadline for direct petitions by relatives has already expired. They can now send a request for legal remedy to the prosecution, which then decides if a petition is justified.

While Rupnik's is probably one of the last annulled verdicts from the communist regime, the state has received almost 700 claims for damages related to the annulments.

The State Attorney's Office has told the STA that the great majority of the claims were filed in 1995-2005 and have already been closed.

The majority have been settled out of court; a settlement has been reached in almost 460 cases and almost 165 claims have been rejected.

Of a total of 126 cases that went to court, 19 lawsuits ended to the benefit of the plaintiffs, while the plaintiffs were not successful in 37 cases, 16 cases ended in a settlement, seven lawsuits have been withdrawn and one rejected.

While the damages claims ranged from EUR 1,200 to EUR 2.5 million, the State Attorney's Office has not provided the figures about the actual damages awarded.

It has explained "the claims ended more than ten years ago" and gathering the data about them would entail time-consuming studying of archived documents.

But it has said the suits and claims for damages were related to a number of different situations, such as imprisonment on the Goli Otok island and at Stara Gradiška prison, both in present-day Croatia, or death sentences.

However, the amount of the damages awarded depended significantly on whether the claim had been made by the victim or their heirs, whether a prison or death sentence had been involved, in which prison the victim had served time and for how long, and to what extent the victim had managed to recover from the experience.

STA, 31 January 2020 - Janez Stanovnik, one of the most notable Slovenian politicians in the period leading up to independence and the face of the Slovenian WWII Veterans' Association after 2003, has died aged 97.

Stanovnik, who was among the first who joined the Partisan liberation movement during the war, was the last president of the Slovenian presidency under the former Yugoslavia between 1988 and 1990 after he served as a member from 1984 to 1988.

After World War II he worked in the federal Yugoslav government and in Yugoslav diplomacy, while he briefly also served as the dean of the Ljubljana Faculty of Economics. He was the executive secretary of the UN's economic commission for Europe from 1968 to 1982.

Between 2003 and 2013 Stanovnik served as the president of Slovenian WWII Veterans' Association and after that he was its honorary president.

Stanovnik was the recipient of a number of honours and was also named an honorary citizen of Ljubljana.

Condolences are already starting to pour in, including from Slovenian President Borut Pahor, who described Stanovnik as an important personality of his era.

Pahor said Slovenians would remember Stanovnik as a Partisan, as strong-charactered, true to his convictions, as somebody with an open spirit and heart.

Parliamentary Speaker and SocDems president Dejan Židan wrote that Stanovnik had been the president of the Slovenian presidency during the pinnacle of democratic change and that he had promoted the values of the liberation movement throughout his life, seeing them "as a key part of our national identity".

STA, 27 January - President Borut Pahor is in Poland to attend a memorial marking the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi concentration camp, accompanied by Slovenian camp survivors. He will lay a candle to honour the victims at a memorial plaque which features an inscription in Slovene since 2008.

The delegation includes Sonja Vrščaj, Elizabeta Kumar Maurič, Marija Frlan and Lidija Rijavec Simčič, who were deported to the camp, as well as Janez Deželak, one of hundreds of Stolen Children, who were separated from their parents after Nazi occupation.

The commemoration was held at the Oswiecim Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau under the auspices of Poland's President Andrzej Duda.

During the Second World War, some six million people died in Poland, including three million Polish Jews, mostly in concentration camps.

International Holocaust Remembrance Day is honoured every year on 27 January, coinciding with the anniversary of Auschwitz liberation.

The Nazis killed more than a million people in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. More than 2,300 people were deported there from Slovenia, with over 1,300 dying before the liberation.

Nikoli več. #NeverAgain #HMD2020 #Auschwitz75 #WeRemember #HolocaustMemorialDay pic.twitter.com/f4VQOGuiRz

— Borut Pahor (@BorutPahor) January 27, 2020

The camp was liberated on 27 January in 1945 by the Soviet troops. Merely some 7,650 ill and debilitated prisoners survived.

Pahor is attending the memorial due to its great symbolic significance, said the president's office. The Slovenian delegation is bearing witness to the horrors of WWII, which are still leaving bitter traces of memories and suffering, said Pahor in a statement.

It is our moral duty that we never forget, that we contribute to a peaceful resolution of all issues and fight to ensure that such atrocities may never happen again, he highlighted.

Meanwhile, Kumar Mavrič expressed satisfaction that the most horrible crimes of the Second World War were living on not just in the memory of the survivors but also in the memory of young generations.

Vrščaj said that the survivors' suffering was part of their fight for freedom, urging the young to love their homeland. "We never said 'if we come home', but 'when we come home'."

Another survivor, Frlan, who turned 100 today, was succinct in saying "a reminder for the young and remembrance for the elderly".

Pahor, who attended the World Holocaust Forum marking the anniversary in Jerusalem last week, will also address a memorial ceremony in Lendava's synagogue on Thursday.

He will wrap up the Holocaust remembrance series of events in May by holding an annual debate featuring the survivors and secondary school students.

Today, a series of events to honour the Holocaust Remembrance Day is taking place in Slovenia, among them a concert of songs performed in secret meetings by an internee of the Sachsenhausen camp. Moreover, the Jewish Cultural centre will screen Shoah, a 1985 film by Claude Lanzmann.

STA, 27 January 2020 - Marjan Šarec is the fourth Slovenian prime minister to resign, following Janez Drnovšek, Alenka Bratušek and Miro Cerar. Below is a timeline of those resignations.

2 December 2002 - Janez Drnovšek resigns half-way into his third term after being elected the president of the republic. The post of the prime minister is assumed by Anton Rop from the ranks of the Liberal Democracy of Slovenia (LDS), the party headed by Drnovšek between 1992 and 2003.

4 May 2014 - Alenka Bratušek, who takes over as the first female prime minister of Slovenia during turbulent political times, resigns after slightly more than a year on the job over discords within her party. Bratušek resigns after losing to Ljubljana Mayor Zoran Janković in the vote for the presidency of the Positive Slovenia (PS) party. The resignation is followed by the collapse of the entire government, and the PS deputy group splits into a part loyal to Janković and the other part inclined to Bratušek.

14 March 2018 - Miro Cerar resigns just months before the regular end of his term. While the economic situation in the country improves during the term of his government, problems also pile up and the last straw, according to Cerar, is the annulment by the Supreme Court of the referendum in which voters endorsed the project to build a new railway servicing the port of Koper.

27 January 2020 - Marjan Šarec resigns with the argument that he is not able to meet the expectations from the people with the minority coalition he has at his disposal. He admits that the government has not been able to carry out major structural reforms and calls for a snap election to be called as soon as possible.

STA, 22 January 2020 - Thirty years to the day, the Slovenian delegation walked out of the 14th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia in Belgrade, in what participants as well as historians deem one of the key moments in the dissolution of Yugoslavia, one that presaged Slovenia's independence.

The delegates of the League of Communists of Slovenia walked out of the congress on the third day of sessions following the rejection of all of their proposals.

Slovenian representatives had called for more autonomy of party organisations in Yugoslav republics and had several proposals aimed towards greater democratisation of Yugoslavia and decentralisation of the League of Communists.

The remaining delegates reacted to the walkout with applause, laughter or boos, with the Belgrade unit of the national television labelling the move as an ill-advised act of separatism.

Following the walkout, the head of the Croatian delegation Ivica Račan proposed that the congress be suspended until the party organisations of the republics examined the situation and found solutions.

The head of the Serbian League of Communists, the future Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, said that this would constitute a dissolution of the congress and called on the remaining delegates to continue the session.

The congress was suspended in less than a week as it was held without representatives of Slovenia, Croatia and Macedonia, in what many see as the start of the disintegration of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia.

The 30th anniversary of the event was marked with a ceremony on Monday hosted by President Borut Pahor, who was among the almost 120 Slovenian delegates to leave the congress on 22 January 1990.

Sociologist Franci Pivec said that the walkout had effectively ended the congress and practically excluded the "ever present" Central Committee of the party from political developments.

Pivec, who was also among the Slovenian delegates, noted that the exclusion of the the League of Communists of Yugoslavia from the political developments at the time was a major event in the run-up to Slovenia's independence.

A month ahead of the congress, the League of Communists of Slovenia adopted a document in which it "expressed its full programme of independence" and called for more Europe-oriented policies in Yugoslavia.

"We came to Belgrade determined that we are going to Europe with Yugoslavia, or without it, if they don't want to go," said Pivec.

He added that even before the congress, it had been clear that the League of Communists of Yugoslavia was "increasingly identifying itself with political views of a military junta" and "openly opposing democratisation."

Ciril Ribičič, the then president of the League of Communists of Slovenia and head of the Slovenian delegation at the congress, said that the plan was to convince others of the need to reform society and the ruling party.

He believes that leaving the congress was the right decision, as "many who were on the opposing side at the event are now sitting in the waiting room for the EU."

Ribičič admitted that it was not simple to maintain unity about the right moment for the walkout, but the delegates nevertheless had left the congress "united, with heads held high and even more convinced that we are on the right path."

President Pahor said that the walkout did not mean that Slovenian communists "returned to Ljubljana with a clear vision that we want to have a Slovenian state".

But the decision did force them to think about alternatives, while at the same time "weakening the federal authorities, in effect lessening their resistance to the democratic aspirations of Slovenians."

Slovenian leaders had diverging views at the beginning of 1990, but the achieved unity, later confirmed at the independence referendum in December, should nevertheless be seen as something exceptional, Pahor added.

In the run-up to the independence referendum, Slovenia declared economic independence from Yugoslavia in March 1990, and the following months a coalition of centre-right called DEMOS won a majority in the first democratic elections in Slovenia.

Following the decisive referendum in favour of independence on 23 December 1990, Slovenia declared independence on 25 June 1991, which was followed by the Ten-Day War and eventual independence from Yugoslavia.

STA, 21 January 2020 - Marija Frlan, who will celebrate her 100th birthday on Holocaust Remembrance Day, spent the last year of WWII in the Ravensbrück concentration camp. She told the STA ahead of her birthday she was not surprised when Nazi secret police came for her, because she had worked against the Germans.

Members of the Nazi secret police came for her in the spring of 1943 and first took her to forced labour. She had to clean and tidy Gestapo offices and other rooms in Škofja Loka for nine months.

During that time, Frlan helped an incarcerated female Partisan, so she was not surprised when she was brought in for questioning and took to prison in Begunje na Gorenjskem.

Her husband was also incarcerated at the time and killed soon after.

After more than two months in Begunje, Frlan and other prisoners were taken to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, north of Berlin.

"We walked from Begunje to Lesce in the snow and waited for the train there, which took us to Munich, where we changed trains and then drove straight to there," she recalls.

Ravensbrück was the biggest concentration camp for women between 1939 and 1945, and also had a male section in the final years. Some 120,000 women and children of 30 nationalities were brought there.

More than 80% were political prisoners, including Frlan.

She said she had made new acquaintances at commemorative events of former internees. But all Slovenians did not all knew each other while at the camp, because they were divided in two sections.

She said no respect could be felt at the camp. "They were Germans, we were convicts."

Being accustomed to hard work since early age, Frlan made it through all the hardships. She said she had quickly learned it was best to stay quiet, calm and not make any trouble.

But even in this ordeal, the internees made some moments even pleasant for themselves. "There's plenty of memories, even a bright moment now and there, I can't deny that."

Frlan spent 13 months at the camp and was liberated on 27 April 1945. But on their way home, the former internees feared both the Red Army and German soldiers and were hiding from them all.

Her journey back to Slovenia in a group of 30 people, including some men, took one month. They walked home but used any transport available along the way.

Frlan remembers the last train they took in Austria before reaching Maribor. "There were some soldiers there, and I didn't know who they were. They told us to get off, so we did, then we got back on, but they told us to get off again.

"So we asked why, if we just want to get home, and they said that whoever comes to Yugoslavia gets shot. But since we were so used to it all we said ok, so we will die at home if we didn't up here."

The soldiers' threat did not materialise, but the group was taken to questioning in Ljubljana after which Frlan could return to her home town of Škofja Loka, but there was noting there waiting for her. "I came home to nothing, neither a husband, nor apartment nor a bed."

Accompanied by a security guard she searched other people's homes to find her property. "My husband was a carpenter, he made everything himself. I got the entire kitchen, a bed and a closet," she said about her quest.

She slowly got back to her feet, found a small apartment and a job and later started a family. "I'm used to everything. There was more bad than good, but life goes on," said Frlan who will turn 100 on 27 January, the day that the UN declared International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

On 27 January 1945, Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi concentration and death camp, was liberated by the Red Army.

If you’ve registered for a free account, you can watch an interview with Marija Frlan on the RTV Slovenia website (in Slovenian, with Slovenian subtitles – just hit CC in the lower right).